Change control procedures are considered a fundamental element of pharmaceutical manufacturing and quality management. It provides a structured and documented approach to evaluating, approving, and implementing changes that may affect product quality, process performance, or the validated state of systems and equipment.

A well-established change control system ensures that no modification to materials, processes, facilities, computerized systems, documentation, or suppliers is introduced without prior assessment and justification. Its purpose is to maintain consistency, prevent unintended consequences, and preserve product integrity throughout the lifecycle.

This article explains the principles of GMP-compliant change control, covering its objectives, classification of changes, step-by-step process, impact and risk assessment activities, and its role in maintaining product quality, operational continuity, and inspection readiness.

What Is Change Control in Pharma?

Change control is a formal, documented system used to manage any planned or unplanned modification that could directly or indirectly affect product quality, patient safety, or the validated state of a process, facility, utility, equipment, or computerized system.

Its objective is to ensure that no change is introduced without:

- Justification,

- Risk assessment,

- Formal approval by designated functions, and

- Documentation of implementation and effectiveness.

Purpose of Change Control

A change control system exists to:

- Preserve consistency in manufacturing and testing processes.

- Maintain the validated state throughout the product lifecycle.

- Prevent uncontrolled changes that may cause deviations, OOS/OOT results, or regulatory non-compliance.

- Provide traceability — documenting why the change was made, who approved it, how it was implemented, and whether it was effective.

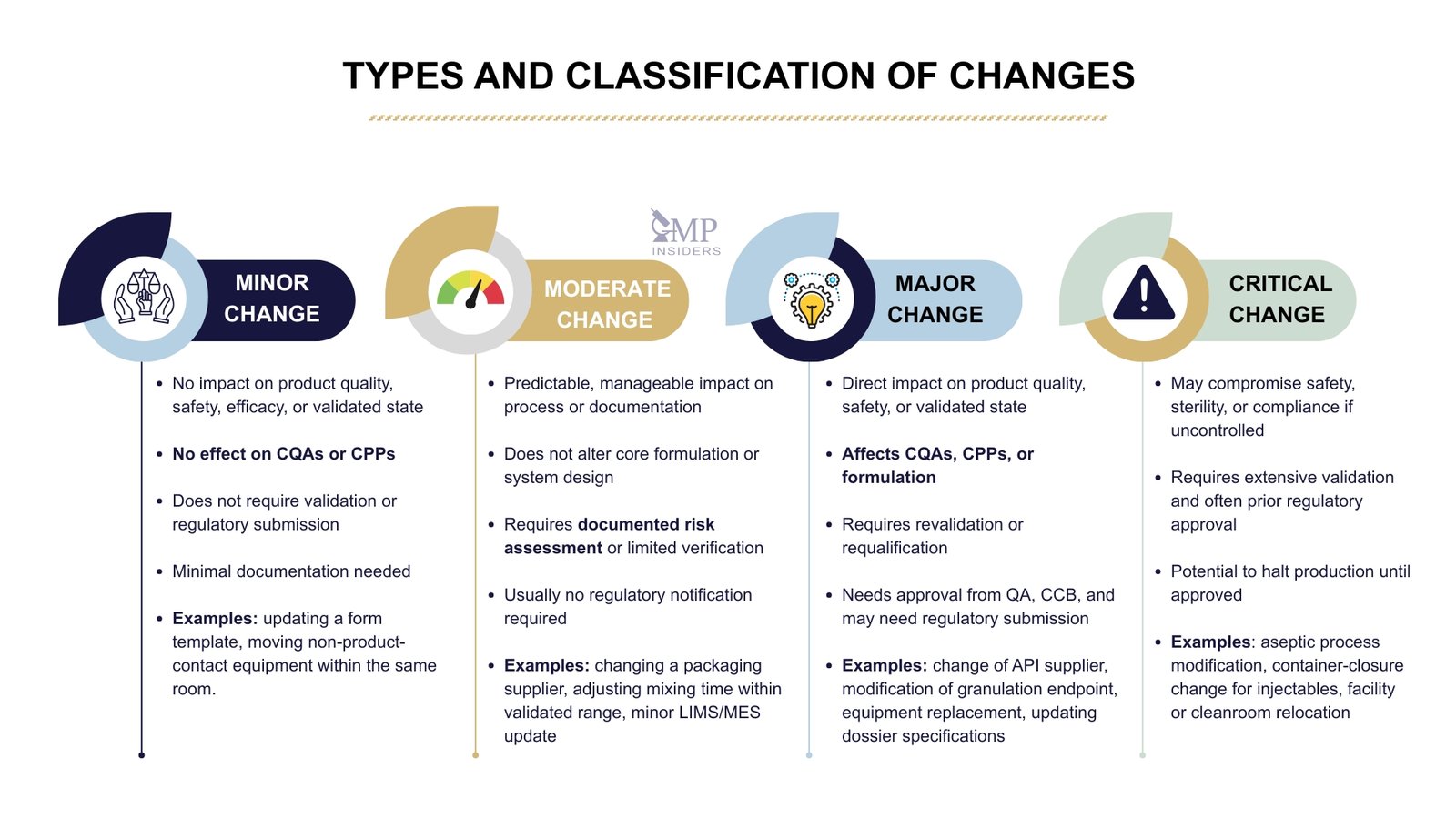

Types and Classification of Changes

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, not all changes carry the same level of risk. A compliant change control system must therefore categorise changes to ensure that the level of assessment, documentation, validation, and regulatory involvement reflects the potential impact on product quality and patient safety.

Classification of Changes Based on Risk

Once the type of change is identified, the next step is to determine its criticality. Classification ensures that the level of documentation, testing, validation, and regulatory involvement is appropriate to the risk posed by the change.

Change classification typically considers:

- Impact on product quality, safety, or efficacy

- Effect on validated processes and equipment

- Need for requalification or revalidation

- Potential impact on regulatory filings or marketing authorisations

- Consequences for patient safety or supply continuity

Minor Change

Minor changes are low-risk modifications that do not impact product quality, safety, efficacy, process performance, or the validated state of equipment or systems. These changes can be implemented with minimal documentation and do not require validation or regulatory submission.

Typical attributes of a minor change:

- No effect on CQAs (Critical Quality Attributes) or CPPs (Critical Process Parameters)

- No impact on validation, cleaning procedures, or regulatory filings

- Only affects format, layout, or non-critical elements

Examples:

- Updating a form template without changing the procedure

- Moving non-product-contact equipment within the same room

Moderate Change

Moderate (or medium-risk) changes may affect the product or process. Still, the impact is predictable, manageable, and can be controlled through risk assessment, testing, or limited validation activities.

Typical attributes of a moderate change:

- May influence process or documentation, but not CQAs directly

- Does not alter the core formulation or validated system design

- Can be managed with documented impact assessment and limited verification activities

- Does not require regulatory notification in most cases

Examples:

- Changing a secondary packaging supplier

- Adjusting mixing time or speed within already validated ranges

- Updating LIMS or MES configuration (without software redesign)

- Revising sampling frequency or IPC test intervals

Major Change

A major change has a direct impact on product quality, safety, validated state, or regulatory documentation, and therefore requires a comprehensive evaluation, revalidation/requalification, or prior regulatory approval.

Typical attributes of a major change:

- Affects CQAs, CPPs, or product formulation

- Requires process validation, equipment qualification, or stability study updates

- Impacts marketing authorisation (MA) or regulatory commitments

- Requires approval from QA, CCB, and possibly regulatory authorities before implementation

Examples:

- Change of API supplier or manufacturing site

- Modification of the granulation endpoint or binder type in the formulation

- Replacement of a major process equipment (e.g., tablet press, granulator)

- Updating specifications in a regulatory dossier

Critical Change

A critical change is a high-risk modification that may compromise patient safety, product quality, regulatory compliance, or business continuity if not controlled. It requires prior approval, significant validation, and often pre-approval from regulatory authorities.

Typical attributes of a critical change:

- Directly impacts product safety, sterility, potency, or bioavailability

- Poses a potential risk of product recall or regulatory non-compliance

- Necessitates extensive validation, stability commitment, or market variation filing

- May involve halting production until approved

Examples:

- Sterile manufacturing process modification (e.g., change in aseptic filling line)

- Change in container-closure system for parenteral products

- Switching from terminal sterilization to aseptic processing

- Relocation of an entire manufacturing facility or cleanroom suite

How to Determine the Classification — Key Questions

A change is classified by answering structured impact questions:

- Does it affect product quality, safety, or efficacy?

- Does it impact a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) or Critical Process Parameter (CPP)?

- Does it require revalidation or requalification?

- Will it change the approved marketing authorisation/dossier (CMC data)?

- Does it impact ongoing commercial batches or clinical trials?

- Could it affect data integrity or computerized system control?

If yes to one or more of the above → the change is likely major or critical.

Regulatory Impact of Change Types

Not every change requires submission to regulatory authorities, but changes that affect a product’s registered details, manufacturing process, equipment, or quality controls may require formal notification or approval.

The extent of regulatory involvement depends on the impact level of the change and whether it affects the Marketing Authorisation (MA), Common Technical Document (CTD), or validated state of a process or system.

To determine whether a regulatory submission is necessary, companies should consider:

- Does the change affect product quality, safety, or efficacy?

- Does it alter what has been filed in Module 3 (CMC) of the dossier?

- Will the change require updated validation, stability data, or comparability studies?

- Does it impact the manufacturing site, process, specifications, container-closure system, or control strategy?

Based on these criteria, changes are typically categorised as internal-only or requiring regulatory notification or approval.

| Impact Level | Regulatory Expectation |

|---|---|

| Minor Change | Managed internally within the Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS). No notification to regulatory authorities. Documentation and justification must still be retained and available for inspection. |

| Moderate Change | Requires internal approval and may require notification to regulatory authorities after implementation, depending on regional regulations (e.g., EU Type IA/IB variations). Supporting data, such as risk assessment or limited validation, may be requested. |

| Major / Critical Change | Requires full assessment, validation, or requalification, and submission to authorities before implementation in most regions. May fall under Type II variation (EU), Prior Approval Supplement (FDA), or equivalent procedure. Implementation should not begin until regulatory approval is granted, unless otherwise justified (e.g., urgent safety measures). |

Temporary Changes (Planned, Short-Term Change Control)

Not all changes in the pharmaceutical industry are permanent. In some situations, companies may implement a temporary change: a planned, time-limited modification introduced for a specific purpose that must be reversed or formally evaluated before it becomes permanent.

These changes still fall under the change control system, as they have the potential to affect product quality, process performance, or compliance if not adequately controlled.

Temporary changes must include:

- Clear justification – why the change is needed and why it cannot follow the standard method.

- Defined duration or batch applicability – how long the change will remain in effect, or for which batches it applies.

- Risk assessment and impact evaluation – ensuring the change does not compromise critical quality attributes (CQAs), critical process parameters (CPPs), or validated conditions.

- Approval before implementation – authorised by QA and relevant departments.

- Reversal or formalization – once the temporary period ends, the process must either be restored to its original state or submitted as a permanent change with full validation and documentation.

Example: using an alternative, calibrated balance for weighing until the primary balance is repaired, temporarily adjusting a process parameter due to equipment malfunction, or using an alternative raw material batch under controlled conditions while awaiting supplier qualification.

Temporary changes must never bypass formal change control procedures, be left open-ended, or continue indefinitely without re-evaluation. Otherwise, they become undocumented permanent changes and a common source of GMP non-compliance.

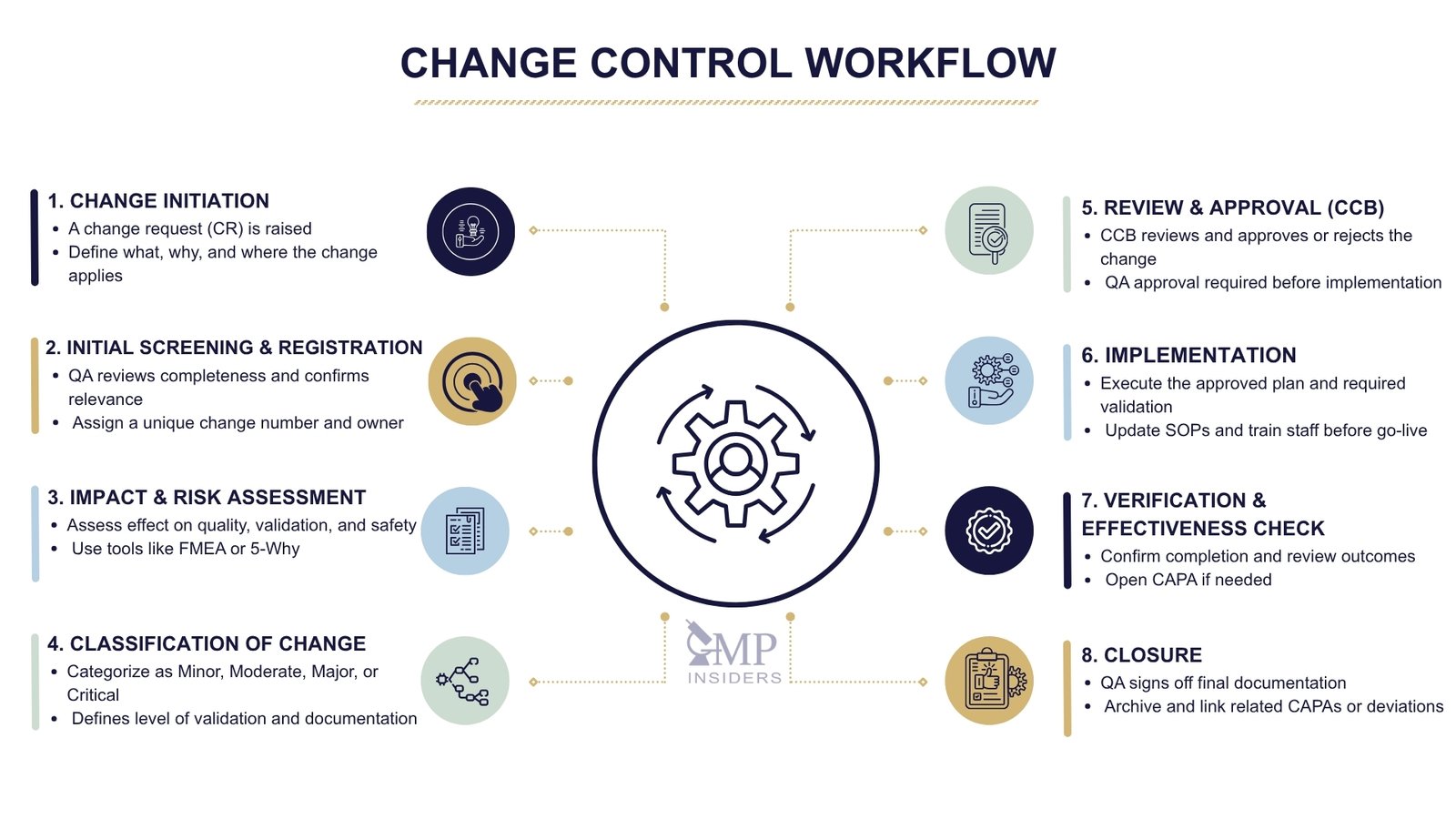

Change Control Process Workflow

A GMP change control system follows a defined sequence of steps that describes the process flow. Each step is connected to the next, but within each step, bullet points make it easy to apply in real procedures, SOPs, and training.

Change Initiation – When a Change Is First Proposed

Every change starts with a recognised need, from production, QC, engineering, validation, or regulatory departments. At this stage, no modification is made; it is only formally proposed.

Key actions:

- A Change Request (CR) is raised.

- The initiator describes:

- What is changing

- Why the change is needed (justification)

- Which process, system, product, or document is affected

- The request is submitted to the change control system.

Initial Screening and Registration

Before evaluation begins, the request must be checked and accepted into the system.

QA or Change Coordinator:

- Reviews the request for completeness and relevance

- Confirms it belongs under the change control system (not just document correction or maintenance)

- Assigns a unique change control number

- Appoints a Change Owner / Responsible Person

Impact Assessment and Risk Evaluation

Only after registration is the change evaluated. This is the most critical step — it determines whether the change is safe, compliant, and feasible.

Impact must be assessed on:

- Product quality and patient safety (CQA impact?)

- Process performance (CPPs, IPCs, batch reproducibility)

- Validated state (need for IQ/OQ/PQ, PPQ, CPV updates?)

- Equipment, utilities, and cleaning procedures

- Computerised systems/data integrity (Annex 11, GAMP 5 considerations)

- Regulatory filings, dossier commitments, stability studies

- Supply chain continuity and documentation updates

Risk assessment tools may include:

- FMEA (Failure Modes and Effects Analysis)

- Ishikawa (Fishbone) diagrams

- 5-Why analysis

- Risk Priority Number (RPN) ranking

- Impact vs probability matrix

Change Classification

The results of the impact assessment determine the classification. This step links the change to the required level of control.

| Classification | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Minor | No impact on CQAs, CPPs, or validated state | Like-for-like equipment part replacement, small process parameter change within approved limits |

| Moderate | Possible impact, but controllable with assessment or limited verification | New secondary packaging supplier, minor LIMS/MES configuration update |

| Major | Direct impact on product, process, or validation status | API/excipient supplier change, modification of CPPs, new manufacturing equipment |

| Critical | High risk to product quality, sterility, or regulatory status | Change in aseptic process, new manufacturing site, container–closure change for sterile product |

Review and Approval – Change Control Board (CCB)

A change cannot move forward without formal approval. This decision is made collectively.

The CCB may include representatives from:

- QA (mandatory)

- QC, Production, Engineering

- Validation, Regulatory Affairs

- CSV/IT, Microbiology (as needed)

The CCB is responsible for:

- Reviewing the impact assessment and classification

- Approving, rejecting, or requesting additional information

- Defining actions, responsibilities, and timelines

- Confirming whether a validation or regulatory submission is required

Implementation of the Change

Once approved, the change is carried out in a controlled manner according to the implementation plan.

Implementation activities can include:

- Equipment modification, process update, software change, or supplier onboarding

- Execution of validation/requalification (IQ/OQ/PQ, PPQ) if triggered

- Updating documents: SOPs, BMR/BPR, cleaning procedures, drawings

- Training relevant personnel before go-live

- Recording any deviations encountered during execution

Verification and Effectiveness Check

Changes must not only be implemented but also verified to work as intended.

Verification tasks include:

- Confirming all actions in the change plan were completed

- Reviewing validation results, batch data, or stability studies

- Checking whether the change caused unintended deviations or trends

- Opening CAPA if results are unsatisfactory

Formal Closure and Documentation

Only after effectiveness is confirmed can the change be closed.

Closure requires:

- Final QA review and approval

- Documentation of all assessments, actions, training, and verification

- Archiving in accordance with data integrity (ALCOA++) principles

- Linking to related CAPAs, deviations, or regulatory submissions

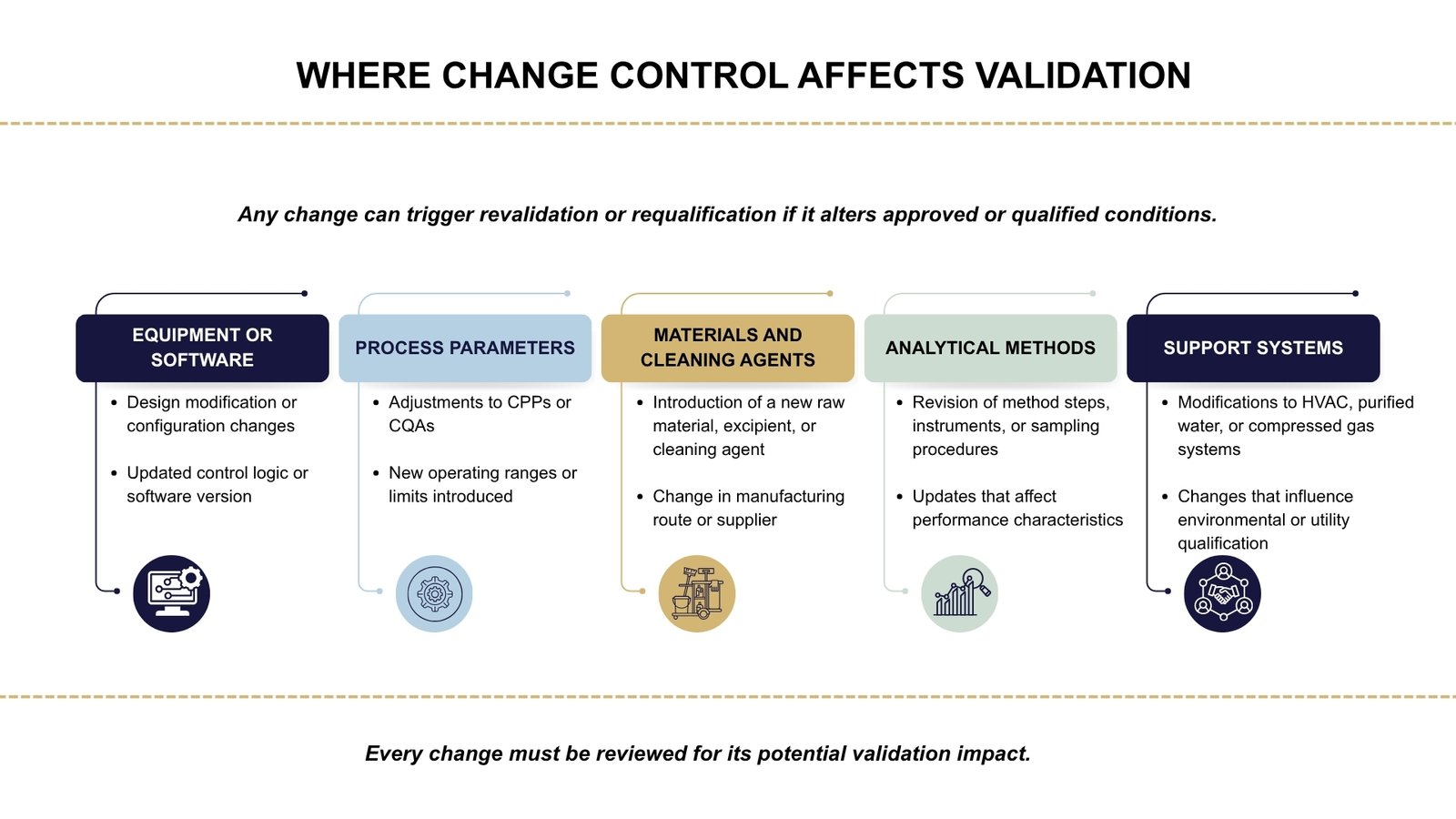

Impact on Validation and the Validated State

Every change control procedure is directly connected to equipment, process, analytical, and cleaning validation activities. Any approved change must be evaluated for its impact on the validated state. If not properly managed, even a minor modification can unintentionally invalidate previously approved processes, methods, or systems.

Why Validation is Affected by Change Control

A process, system, or equipment remains in a validated state only as long as it operates within approved parameters, materials, and procedures. Once a change is introduced, this state can be compromised unless:

- The change is risk-assessed

- Validation impact is identified

- Requalification/revalidation is performed where necessary

See Also: Qualification vs Validation in GMP

Types of Validation Impacted by Change Control

When a change is introduced, one of the first questions to answer is whether it affects the validated state of equipment, processes, analytical methods, or supporting systems. If the change has the potential to alter a previously approved or qualified condition, requalification or revalidation is required.

This impact is commonly seen in the following areas:

A change may trigger validation activities if it:

- Alters a Critical Process Parameter (CPP) or Critical Quality Attribute (CQA)

- Modifies equipment design, software, or operating controls

- Introduces a new material, cleaning agent, or manufacturing route

- Affects previously approved analytical methods or sampling procedures

- Impacts systems essential to product quality, such as HVAC, water systems, or compressed gases

Key Questions to Determine Validation Impact

During change control assessment, QA/Validation should determine:

- Does the change impact Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) or Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)?

- Does the change affect qualified equipment, utilities, or software?

- Will it require IQ/OQ/PQ or full/partial revalidation?

- Does it impact process validation (PPQ/CPV) or analytical method performance?

- Is comparative data or equivalence testing required?

- Does it affect cleaning validation limits or worst-case product selection?

- Does the change need regulatory submission or prior approval from authorities? (e.g. Type II Variation, PAS)

Linking Change Control to the Validation Lifecycle

Any approved change must be evaluated not only for its risk but also for its impact on the validation lifecycle. A modification can affect different stages of equipment, process, or system validation. If not managed correctly, it may result in loss of validated state or non-compliance with Annex 15 and ICH Q10 requirements.

To maintain control, change control and validation must work together. This means that:

- No change is implemented without assessing its impact on qualification or validation.

- Each stage of validation, from design to continued process verification, may need to be updated depending on the scope of change.

- Revalidation or requalification is required when approved parameters, materials, or system functionality are altered.

When Are Change Control Procedures Required

Not every update in pharmaceutical manufacturing requires a formal initiation of a change control procedure. However, distinguishing between changes that need structured evaluation and those that do not is essential for maintaining compliance without overloading the system with unnecessary documentation.

A change should undergo the change control process when it has the potential to impact product quality, patient safety, data integrity, or the validated state of equipment, processes, or systems. Conversely, routine actions that do not affect these elements may be managed through maintenance records, document revisions, or administrative updates.

Changes That Require Change Control

Changes must be formally evaluated and approved when they introduce a potential risk to manufacturing consistency or regulatory compliance. Typical examples that necessitate change control include modifications to materials, processes, equipment, or quality documentation.

Examples when change control is required:

- The modification affects materials or suppliers

- Manufacturing parameters or validated processes are adjusted

- New equipment is introduced or existing equipment is modified

- Cleanroom classification, layout, or environmental controls are altered

- Computerized systems (LIMS, MES, eQMS, PLC) are upgraded or reconfigured

- Specifications, sampling plans, or analytical methods are changed

- The change impacts the marketing authorization or regulatory dossier

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Raw Materials | API supplier change, excipient grade modification |

| Process Parameters | New granulation endpoint, mixing speed adjustment |

| Equipment/Facility | Installation of new tablet press, HVAC modifications |

| Computerised Systems | LIMS upgrade, new eQMS configuration |

| Documentation | Revision of BMR/BPR, updated IPC limits |

| Cleaning/Validation | New cleaning agent, modified product campaign sequence |

| Regulatory Impact | Specification change in dossier, stability protocol update |

Changes That Do Not Require Change Control

Some updates are administrative or maintenance-related and do not impact GMP processes. These can be handled outside the formal change control system, typically via controlled documentation or maintenance logs.

Examples when change control is not required:

- There is no impact on product quality, validation status, or GMP compliance

- The activity involves routine maintenance or calibration without modification

- Document formatting or typographical corrections are made with no procedural change

- Office-level, non-GMP tools or systems are updated

| Situation | Examples |

|---|---|

| Administrative Updates | Formatting SOP cover pages, updating the company logo |

| Routine Maintenance | Replacing like-for-like HVAC filters, scheduled lubrication |

| Calibration | Standard instrument calibration without adjustment |

| Minor Documentation Edits | Typographical correction, aligning numbering or fonts |

| Non-GMP Facility Updates | Office repainting, furniture replacement |

Borderline Situations — Apply Risk-Based Decision Making

Some changes are not clearly classified and require a documented justification. In such cases, QA should confirm whether change control is appropriate based on risk.

| Scenario | Change Control Required? |

|---|---|

| Equipment moved to a new room | Yes — affects qualification and material/personnel flow |

| Replacement of a component with a different brand/specification | Yes — requires evaluation of functional impact |

| Temporary deviation that becomes permanent | Yes — deviation → CAPA → change control |

| Revision of SOP due to audit finding | Yes — procedural change must be controlled |

| ERP update not used for GMP data | No — if no link to quality/GMP records |

| Replacement of an identical spare part during maintenance | No — if specification and function are unchanged |

Common Pitfalls and GMP Deficiencies in Change Control Systems

Even when a change control system exists, errors often occur in its application. Regulatory inspections frequently highlight deficiencies such as undocumented changes, poor risk assessment, and closure without verification. These issues can compromise product quality, leading to inspection findings, warning letters, or loss of validated status.

Changes Implemented Before Approval

One of the most frequent GMP violations is implementing a change before documenting it.

Typical examples include:

- Installing new equipment before completing change control documentation

- Adjusting process parameters during production without risk assessment

- Updating LIMS/PLC software before approval from QA or CSV teams

Why this is a problem:

It bypasses formal review, risk evaluation, and validation, making it impossible to prove the process remained in a controlled state.

Incomplete or Generic Risk Assessments

Change requests often include superficial risk assessments copied from earlier changes or limited to a single department.

Common issues:

- “No impact on quality”, stated without justification

- No evaluation of impact on CQAs, CPPs, cleaning validation, or data integrity

- No reference to ICH Q9 tools, such as FMEA or control of residual risk

Consequence:

The change may proceed without understanding downstream effects, increasing the chance of deviations, OOS/OOT, or batch rejection.

Misclassification of Change Severity

To avoid workload, timelines, or validation, some changes are incorrectly classified as “minor.”

Examples:

- API or excipient supplier change marked as minor

- HVAC system modification classified as a documentation-only update

- Process parameter shifts beyond validated ranges are not flagged as critical

Impact:

Significant changes proceed without regulatory submission, validation, or full impact assessment, leading to non-compliance.

Change Closed Without Effectiveness Check

Some change records are closed immediately after implementation, without assessing whether the change actually worked as intended.

Missed actions include:

- No verification of batch performance or stability data post-change

- No trending of deviations, complaints, or IPC failures

- No evaluation of CAPA effectiveness (if linked)

Why it matters:

A change is only complete when it has been implemented, verified, and proven to have no unintended consequences.

Documentation Gaps and Lack of Traceability

Regulators expect full traceability from the moment a change is proposed to its final closure.

Typical observations include:

- Missing justification for change

- No linkage to related SOP updates, validation protocols, or training records

- Training performed but not documented before the effective date

- No record of who approved or implemented the change

See Also: Types of GMP Documentation Used in Pharma

Regulatory Basis & Guidelines on Change Control

Change control is an essential part of the Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) and is required by all major regulatory frameworks worldwide.

While terminology and format may differ across regions, pharmaceutical regulatory authorities consistently expect that any change that may affect product quality, patient safety, data integrity, or the validated state must be assessed, documented, justified, approved, and implemented in a controlled manner.

EU GMP Guidelines

Change control is referenced throughout the following EU GMP guidelines:

- Part I, Chapter 1 – Pharmaceutical Quality System requires that all changes to processes, equipment, systems, or documents that may affect product quality are formally evaluated and approved by authorized personnel.

- Annex 15 – Qualification and Validation defines change control as a structured system for assessing proposed changes, evaluating their impact on the validated state, and determining whether requalification or revalidation is required.

- Annex 11 – Computerised Systems specifies that updates, configuration changes, and software modifications must be managed through a controlled change process to protect data integrity.

For active substances, EU Regulation 1252/2014, Article 14 requires manufacturers to assess how changes to API processes may affect impurity profiles, quality, or regulatory compliance before implementation.

FDA Regulations

The FDA expects change control procedures to be integrated into the company’s quality system and overseen by the Quality Unit.

Relevant sections include:

- 21 CFR 211.22 – The Quality Unit must review and approve all changes that could impact the production or control of drug products.

- 21 CFR 211.100 – Requires written procedures for production and process control; any changes must be drafted by qualified personnel and approved by the Quality Unit.

- 21 CFR 211.160 – Laboratory control procedures, including changes to analytical methods or specifications, must be documented and justified.

- 21 CFR 211.180 – Significant changes to equipment, processes, and procedures must be recorded and retained.

For combination products and devices, change control expectations are also defined in 21 CFR 820.30 and 820.40.

ICH Guidelines

The ICH guidelines provide a globally harmonized foundation for how pharmaceutical companies should manage changes throughout the product lifecycle.

- ICH Q9 – Quality Risk Management: This guideline establishes that all changes must be assessed using a risk-based approach. It emphasizes identifying potential risks to product quality and patient safety before a change is approved or implemented.

- ICH Q10 – Pharmaceutical Quality System: ICH Q10 defines change management as a core element of the Pharmaceutical Quality System. It requires that changes are formally evaluated, justified, approved by appropriate functions, and verified for effectiveness once implemented.

- ICH Q12 – Product Lifecycle Management: ICH Q12 introduces tools and frameworks for managing post-approval changes in a structured, science-based manner. It supports predictability by defining when changes can be managed within the company’s PQS and when they require regulatory authority notification or approval.

FAQ

What is the Difference Between Change Control and Deviation?

A deviation documents an unplanned or unintended event, such as a process failure or non-compliance with SOPs. Change control is used for planned modifications that are evaluated before execution. If a change is made without prior approval, it is recorded as a deviation and must go through deviation/CAPA first.

After root cause analysis, the correction may be formalized through change control if it needs to become permanent. In short, deviation is reactive, and change control is preventive/proactive.

What Happens When a Change Is Urgent and Cannot Wait for Full Approval?

In urgent situations (e.g., equipment breakdown affecting a critical batch), a temporary change or emergency change control process may be used. This allows fast approval from QA and key stakeholders with limited documentation initially.

Risk must still be assessed, and the change must not compromise patient safety or product quality. Afterward, all documentation, impact assessment, and validation must be completed retrospectively. Emergency changes must not become routine practice.

What Is Meant by “Effective Date” in Change Control?

The effective date is the date from which the approved change becomes active in routine operations. It is determined after CCB approval, document updates, training completion, and (if required) validation.

No batch, process, or activity should use the new method before this date. If the effective date is missed, the change must be rescheduled or reassessed. It ensures traceability in batch records, audit trails, and regulatory compliance.

Can a Change Be Reversed or Cancelled After Implementation?

Yes, if a change results in unexpected problems, it may be reversed through a rollback change control. This reversal must be formally documented, risk-assessed, and approved like any other change.

Any intermediate batches manufactured under the change must be evaluated for impact. If quality or safety is compromised, deviation or recall procedures may be activated. A CAPA may then be required to address the failure.

How Long Should a Change Control Remain Open?

Ideally, change controls should be completed within a predefined timeframe (e.g. 30–90 days depending on severity). Extended open change controls are considered poor system controls during inspections.

Only justified cases, such as validation campaigns, regulatory awaiting periods, or long-term stability studies, may remain open longer. KPIs often track overdue change controls. If significantly delayed, they may require deviation or escalation.

Can Contractors or Suppliers Initiate Change Control?

External suppliers cannot open change control directly within a company’s QMS. However, they can submit a change notification if they modify raw materials, testing methods, or manufacturing processes.

The pharmaceutical company must then evaluate this change internally via its own change control system. If the change impacts registered specifications, regulatory updates may be required. Supplier qualification and technical agreements should define how such changes are communicated.

Final Thoughts

A well-functioning change control system does not prevent change. Instead, it provides a structured pathway for change that does not compromise patient safety, regulatory compliance, or process consistency. It connects departments, links risk assessment with decision-making, and ensures that documentation, validation, and training are completed before the change becomes part of routine operations.

In modern manufacturing environments, change control is evolving. Digital systems, electronic QMS platforms, data integrity expectations, and real-time decision-making demand more than paper approvals. Change control is becoming a lifecycle tool that supports continuous improvement rather than a one-time administrative exercise.

Ultimately, the value of change control lies in its purpose. It exists to ensure change occurs in a controlled, science-based, risk- and responsibility-informed way. Companies that treat it as a strategic process rather than a checklist are better prepared for inspections, more resilient in the face of failures, and more capable of innovation without compromising compliance.