Most pharmaceutical companies still implement computerized system validation (CSV) as a documentation exercise rather than applying the risk-based lifecycle control defined by GAMP 5. This is where compliance starts to fail.

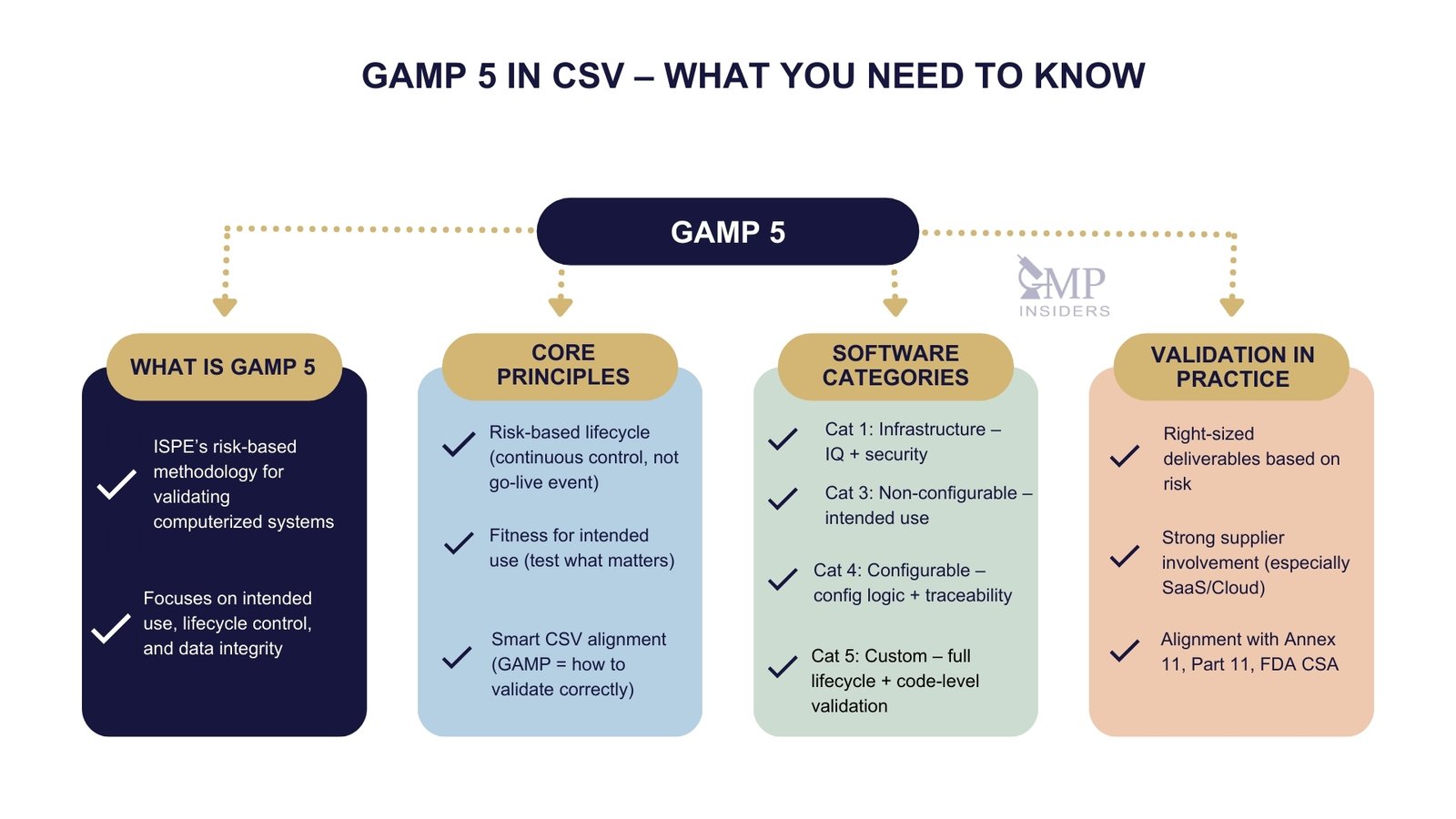

GAMP 5, developed by ISPE, is the globally accepted methodology for ensuring that computerized systems are fit for intended use, proportionately validated, and continuously controlled throughout their lifecycle, not just at go-live.

Unlike generic validation approaches, GAMP 5 focuses on intended use, risk impact, and traceability rather than on generating large volumes of test scripts. It has become the strategic foundation for modern CSV execution, Annex 11 and FDA Part 11 alignment, and future readiness under FDA CSA expectations.

This article breaks down what GAMP 5 really is, how it differs from traditional CSV thinking, and how its software categories, methodology, and lifecycle approach directly influence validation strategy in GMP environments.

What is GAMP 5?

GAMP 5, officially known as Good Automated Manufacturing Practice, is a globally recognized ISPE guidance document that provides a structured, risk-based approach to managing and validating computerized systems used in GMP environments. It is not a regulation and does not replace Annex 11 or 21 CFR Part 11. Instead, it serves as the most practical and widely accepted interpretation of what regulators expect when they refer to “a validated system” in pharmaceutical operations.

GAMP 5 encourages critical thinking over checkbox execution. It enables companies to reduce unnecessary testing effort and documentation while increasing focus on areas that directly affect product quality, patient safety, data integrity, and regulated decision-making.

Historical Evolution of GAMP

The GAMP framework has evolved over three decades, reflecting the industry’s evolving understanding of computerized system risk. Early versions of GAMP were driven mainly by IT and engineering departments, focusing heavily on system compliance rather than process impact. By today’s standards, these interpretations were rigid, sequential, and documentation-heavy.

- GAMP 3 and prior were infrastructure- and technology-centric, focused more on “is the software compliant?” rather than “does it affect product quality and data integrity, and how?”

- GAMP 4 introduced a structured methodology but remained highly procedural and generated excessive documentation, a common reason many companies still struggle today.

- GAMP 5 marked the actual shift. It introduced the concepts of risk-based thinking, lifecycle approach, and fit-for-intended-use assurance rather than validation through sheer documentation volume.

The pharmaceutical industry’s shift toward digitalization made these evolutions necessary. The original GAMP 5 was strong, but by 2022, the acceleration of cloud, SaaS, AI/ML, configurable platforms, and supplier-controlled infrastructure led to the release of the GAMP 5 Second Edition, which introduced modernized thinking without discarding the original foundation.

Key Enhancements in GAMP 5 Second Edition

The Second Edition of GAMP 5, published in 2022, does not replace the original guidance; instead, it refines it for a digital, supplier-driven world. The core principles remain intact. What has changed is the interpretation of how those principles should be applied in practice to avoid both under-control and over-validation.

The most significant enhancements include:

- Stronger emphasis on critical thinking over procedural box-ticking. GAMP warns against excessive documentation that adds no value in reducing risk.

- Modern technology coverage, with specific guidance for cloud-hosted SaaS, decentralized architectures, AI/ML-driven decision engines, and rapidly evolving digital platforms.

- Shared accountability model, acknowledging that suppliers now carry primary responsibility for software quality and continuous updates, therefore, validation can no longer be isolated within the regulated company.

- Alignment with FDA’s Computer Software Assurance (CSA) — shifting from proof-by-volume to proof-by-relevance, particularly in test strategy and documentation scope.

- Integration with data integrity expectations, making it clear that validation does not stop at functionality, but must ensure long-term reliability and traceability of data throughout the lifecycle.

– Advertisement –

| Area | First Edition | Second Edition |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Sequential | Critical thinking |

| Technology | Traditional | Cloud, SaaS, AI/ML |

| Development | V-model | Agile accepted |

| Responsibility | Company-only | Shared with suppliers |

The updated edition focuses less on introducing new rules and more on encouraging the industry to apply GAMP 5 with intention, logic, and proportionality. It officially acknowledges that moving fast and staying compliant are not opposites, provided risk is truly understood.

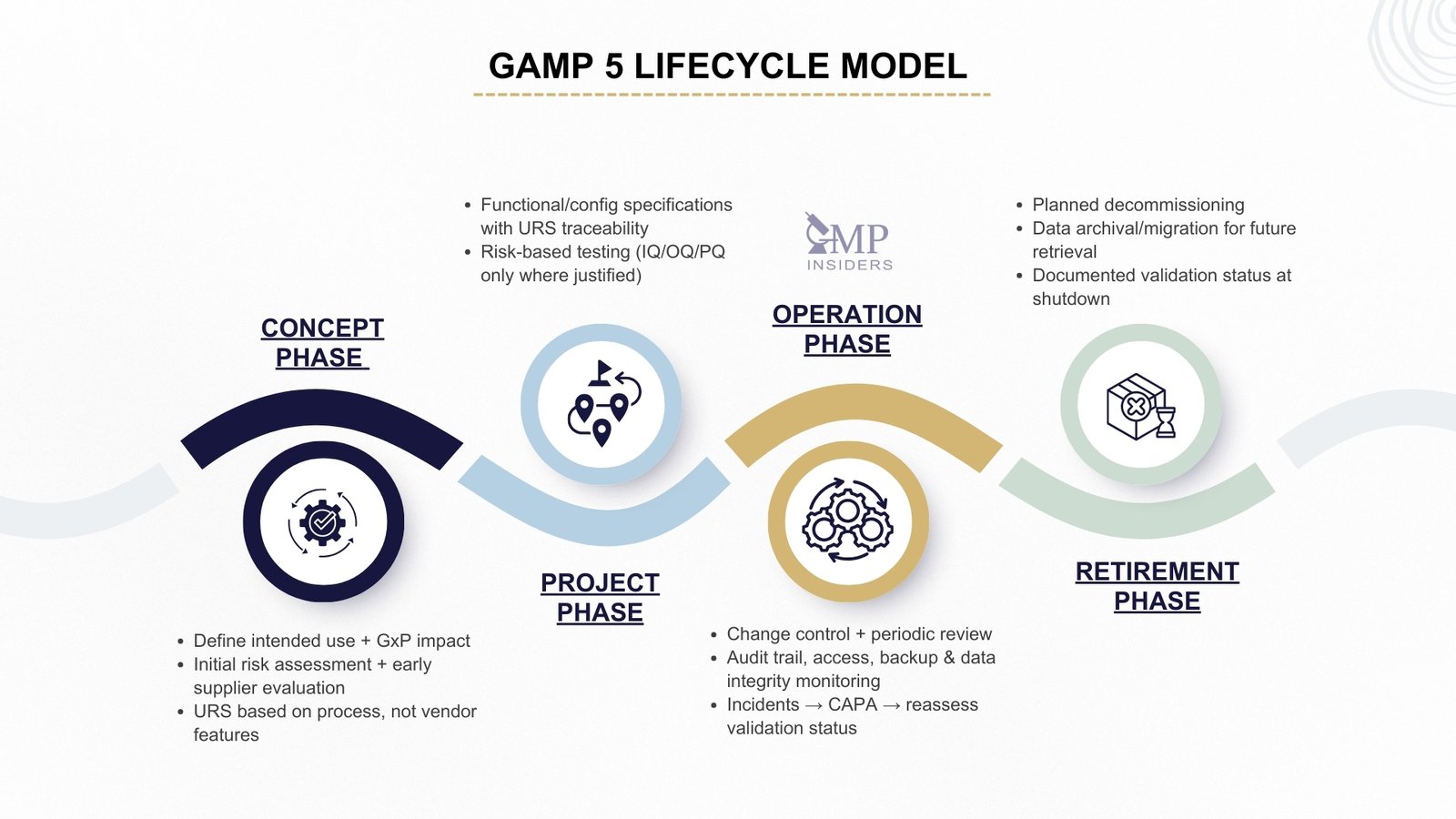

GAMP 5 Lifecycle Model

GAMP 5 defines computerized system validation as a continuous lifecycle, not a one-time qualification event. Each phase has a specific purpose, different stakeholders, and a different level of validation control. This is where most companies fail: they only validate during implementation and neglect the earlier thinking stages and the post-go-live control, where most audit findings now occur.

Concept Phase

The purpose of this phase is to justify the system before selecting or buying anything, not after it is installed.

Key activities:

- Define the business process and intended GxP use.

- Identify whether the system will impact product quality, patient safety, or data integrity.

- Draft User Requirement Specification (URS) that reflects business reality, not copied vendor features.

- Perform an initial high-level risk assessment: will this system affect batch release decisions, electronic records, patient data, etc.?

- Evaluate suppliers early, not after purchase — maturity level, CSV readiness, support model, documentation quality.

Why this phase matters:

- If wrong here, the entire validation is fundamentally flawed, regardless of later testing efforts.

- Annex 11 & FDA now expect risk thinking before a system is even acquired.

Project Phase

This phase is where most companies mistakenly believe validation starts, but under GAMP, it is simply the execution phase of already established control logic.

Key activities:

- Define Functional Specifications and Configuration Specifications (not always full design specs, depending on category).

- Ensure traceability back to UR: early traceability, not after testing.

- Define a risk-based test strategy (not one-size-fits-all IQ/OQ/PQ).

- Execute IQ (infrastructure), OQ (functionality), PQ (process fit-for-use), but only to the extent justified by risk.

- Document deviations properly; not every deviation is critical, but every deviation must be understood.

Goal of this phase:

- Prove that the system is fit for intended use.

- Avoid “testing everything to be safe,” as GAMP 5 explicitly warns against it.

Operation Phase

Most regulatory observations occur here because companies validate once and then stop monitoring.

Key operational control elements:

- Change control: structured, risk-assessed, not overcomplicated.

- Periodic reviews: assessment of validation status, audit trail integrity, and supplier performance.

- Incident management & CAPA linkage: validation status must be reassessed when failures occur.

- Backup, access, data integrity monitoring: regulators now heavily test for this phase, not just initial validation.

Why this phase is critical:

- Validation is only valid as long as the system remains under control.

- Annex 11 explicitly demands continuous validation assurance.

Retirement Phase

Most companies fail this phase completely; either they unplug the system or leave its data “somewhere”.

What must happen:

- Formal decommissioning plan: including data retention obligations.

- Data archival or migration: must ensure future regulatory retrieval capability.

- Record of validation status at shutdown: the regulator should be able to reconstruct evidence years later.

End goal:

- The system is shut down in a way that regulatory records remain intact, retrievable, and trustworthy.

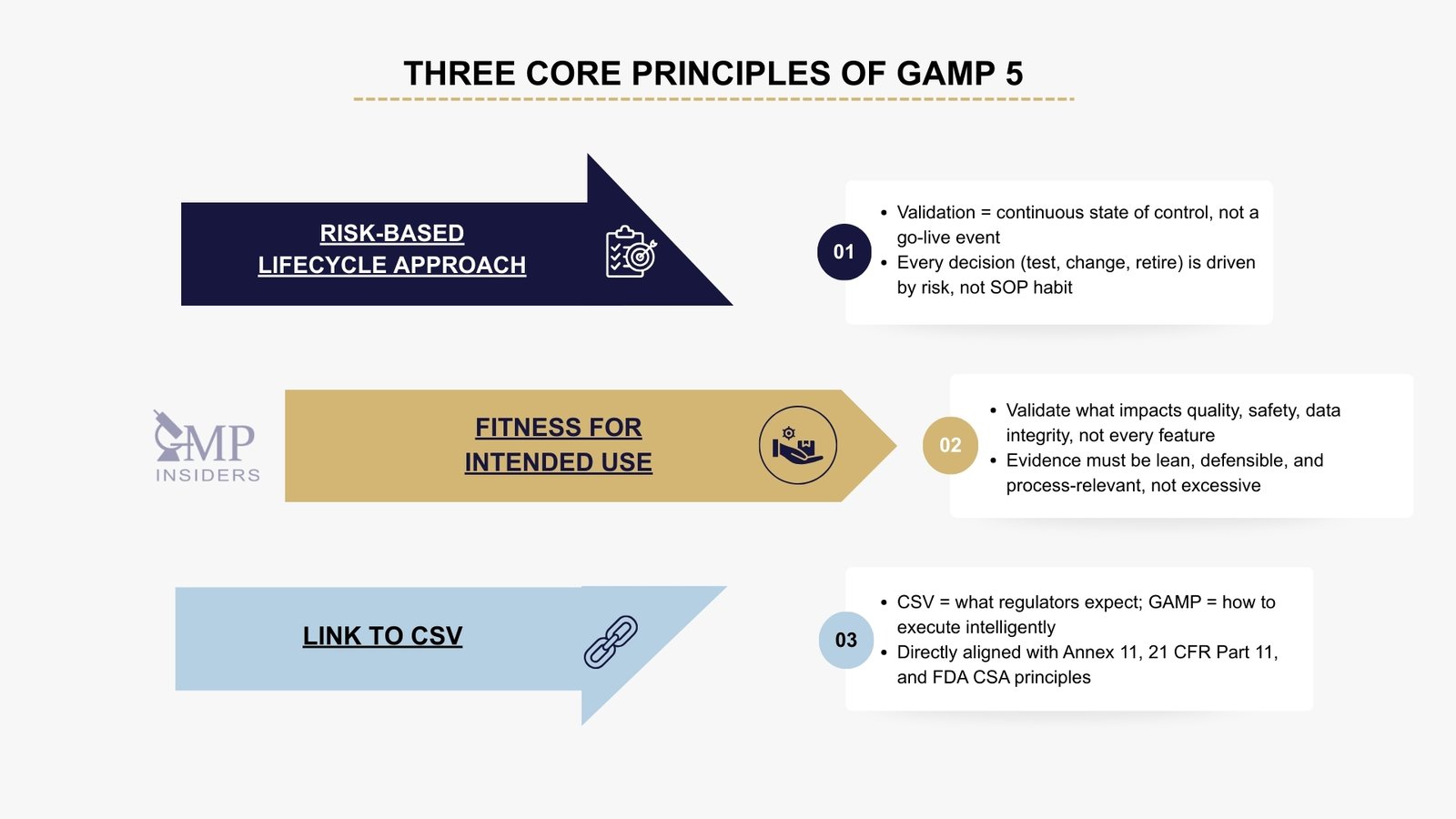

Core Principles of GAMP 5

GAMP 5 is built around three fundamental principles that define how computerized systems should be validated and controlled in a GMP-regulated environment. These principles move validation away from procedural repetition and toward intelligent, risk-based assurance.

Risk-Based Lifecycle Approach

GAMP 5 defines validation as a continuous state of control, not a one-time activity that ends after system qualification. A computerized system remains compliant only as long as it is actively managed throughout its lifecycle, from selection and implementation to operational use, controlled change, and eventual retirement. Validation is therefore not a project milestone but a living assurance process, continuously aligned with process risk.

The intent is to prevent companies from treating validation as a document package created during go-live and forgotten afterward. GAMP 5 expects ongoing control, not cyclic revalidation driven by arbitrary time intervals or triggered only when audits approach. Every decision, whether to test, re-test, change, or retire, should be driven by risk impact, not habit or SOP tradition.

In practice, this means that the validation strategy must evolve with the system. When functionality, configuration, data flow, or supplier responsibility changes, the risk is re-assessed rather than blindly revalidated. Control is maintained, not just proven once, and this is precisely where inspectors now focus most during audits.

SEE ALSO: Quality Risk Management in Computer System Validation (CSV)

Focus on Fitness for Intended Use

GAMP 5 emphasizes that validation must prove that a system is fit for its intended use within the specific GMP process it supports, not for every possible function it technically offers. This is a critical distinction. Most audit findings today do not stem from missing evidence, but from irrelevant, excessive, and poorly justified documentation created “just in case.”

GAMP 5 actively discourages:

- Testing every system feature simply because it exists

- Blindly following generic test templates or vendor scripts

- Duplicating supplier testing without justification

- Using documentation volume as a proxy for control

Instead, the focus is on purpose and consequence. The question is not “Did you test everything?” but “Did you test what actually matters to product quality, patient safety, or data integrity?” This means validation evidence should be sharp, process-driven, and defensible, lean enough to maintain, but strong enough to pass regulatory scrutiny without excuse or overcomplication.

Link to CSV

GAMP 5 is not a replacement for CSV; rather, it is the thinking framework upon which modern Computerized System Validation is built. CSV describes what must be achieved in regulatory terms (a validated, controlled system), while GAMP 5 defines how validation should be approached intelligently, proportionately, and based on real process risk.

This is why regulators such as the FDA, EMA, and MHRA expect companies to follow GAMP principles, even if they are never explicitly referenced during inspections. The shift toward the FDA’s Computer Software Assurance (CSA) is not a departure from GAMP; it is a direct evolution of its principles: critical thinking over template-following, and assurance over document generation.

When applied correctly, GAMP 5 prevents validation from becoming a document-heavy IT exercise and instead anchors CSV to its true goal, ensuring controlled, defensible, and continuously reliable system performance in a GxP environment.

SEE ALSO: CSV vs CSA

GAMP 5 Software Categories

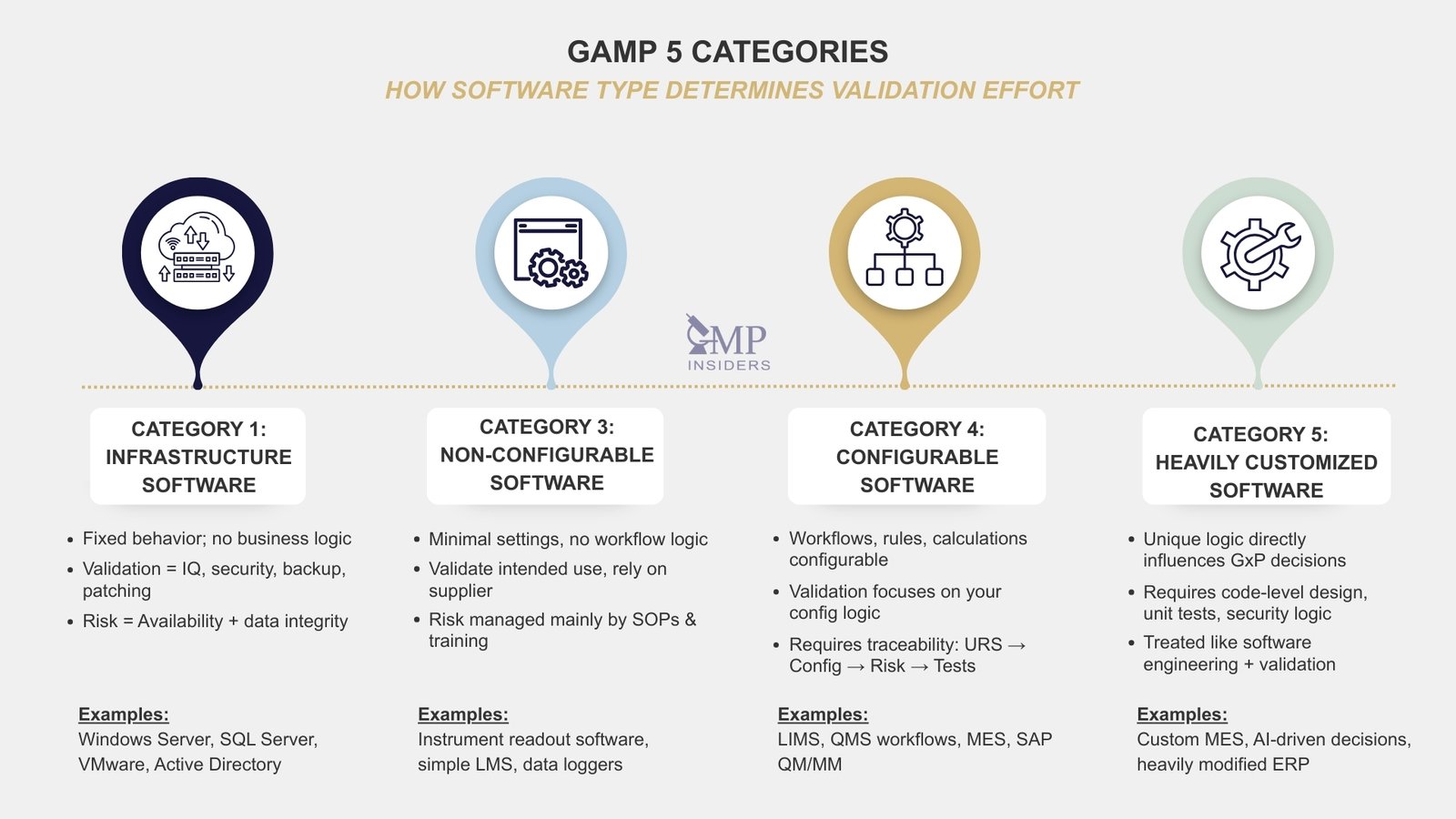

One of the most misunderstood areas of GAMP 5 is the software categorization model. Companies often guess a category or inflate it “to be safe”, which only leads to unnecessary validation effort and wasted resources.

The purpose of categorization is not to complicate CSV but to scale the validation effort proportionally to how much the system can impact product quality, data integrity, or batch release decisions.

GAMP 5 makes a clear distinction between:

- Systems that cannot be meaningfully changed (low validation burden)

- Systems that you configure to match your GMP process (moderate to high validation burden)

- Systems that are custom-developed or fundamentally rewritten (full lifecycle scrutiny)

Category 1 — Infrastructure Software

Category 1 includes foundational technology components such as operating systems (e.g., Windows Server, Red Hat Enterprise Linux), database engines (e.g., Oracle, SQL Server), hypervisors (e.g., VMware ESXi), and network infrastructure services required to host or support GxP applications.

These systems do not execute GxP decisions directly, but everything above them depends on their integrity, availability, and security.

Typical examples include:

- Windows Server hosting a validated LIMS application

- Oracle or SQL Server as the database backend for an MES or QMS

- VMware virtualization layer running multiple qualified GxP systems

- Active Directory for user authentication and role-based access control

Although Category 1 systems rarely require functional testing, they are absolutely not exempt from validation. GAMP 5 makes it clear that these systems must be qualified, not validated in the traditional test-script sense, but proven to be installed, secured, and maintained under controlled conditions.

In practice, this means:

- Installation Qualification (IQ) to verify the correct setup and hardened configuration

- Documented procedures for patching, backup, disaster recovery, and cybersecurity

- Clear ownership between IT and Quality, ensuring that changes are assessed before deployment

- Evidence that the system will not compromise the validated applications it supports

You do not test “whether Windows Server performs calculations correctly”. You prove that it will not fail, corrupt data, or allow uncontrolled access, because if it does, every validated system on top of it becomes unreliable.

Category 3 — Non-Configurable Software

Category 3 systems are standard software applications that cannot be altered beyond basic settings. The vendor fixes their functionality but does not allow deep customization of workflows or decision logic. These tools are often used to support a GxP process, but do not independently control or drive critical decisions.

Typical examples include:

- Basic analytical instrument software used only to display or record raw values (e.g., UV/Vis spectrophotometer readout software)

- A simple Learning Management System (LMS) used only for tracking completion status, not automating certification logic

- A stand-alone temperature data logger interface used purely for manual export and review

- A printer driver used for label output, without embedded logic that influences data

Because these systems cannot be configured to execute GMP-relevant business rules, the validation focus differs significantly from that in Category 4 or 5. The assurance here is mainly about confirming the intended use rather than deep functional risk testing.

In practice, Category 3 validation typically involves:

- Basic functional confirmation to ensure the system performs its expected task reliably

- Leveraging supplier documentation and certificates rather than duplicating test coverage

- Strong procedural and training controls are necessary because the primary risk comes from misuse, not malfunction

- Clear SOPs defining how the system is used, reviewed, and maintained, rather than technical testing alone

Category 3 systems are not “low importance”, but they do not justify Category 5-level testing effort. The risk is managed primarily through controlled use and documented procedures rather than exhaustive software qualification activities.

Category 4 — Configurable Software

Category 4 systems are configurable platforms in which the supplier provides the core software, but the regulated company shapes the system’s behavior. Unlike Category 3 tools, these systems allow modification of workflows, data logic, approval paths, calculations, and user permissions, meaning your choices determine the system’s compliance risk.

Typical examples include:

- LIMS configured to automate sample login, calculation logic, and release rules

- QMS platforms where workflows for deviations, CAPAs, and change controls are configured

- MES is used to control manufacturing steps, batch records, and in-process checks

- ERP modules (e.g., SAP QM/MM) configured to drive material status, release, and procurement logic

This category represents the majority of systems in today’s digital GMP landscape, and is also the category most commonly over-validated or validated incorrectly.

Unlike Category 3, Category 4 validation is not about proving the software works in general; it is about demonstrating that the configuration you implemented is correct, traceable, risk-justified, and aligned with GMP process control.

In practice, effective Category 4 validation includes:

- Mapping URS → Configuration Specification → Risk Assessment → Test Strategy

- Testing only what was configured, not every possible vendor feature

- Documenting who made each configuration decision and why

- Ensuring QA, not IT alone, reviews and approves configuration logic

- Viewing supplier as a lifecycle partner, not as an external vendor

Category 4 requires mature risk-based thinking, not maximum testing effort, but targeted assurance based on impact. This is the category where GAMP 5’s critical thinking principle is most visibly tested during audits.

Category 5 — Custom or Heavily Customized Software

Category 5 covers software that is either fully custom-built or significantly modified beyond standard configuration. This includes systems in which the regulated company or a contracted developer defines or alters core logic that directly affects decision-making.

Typical examples include:

- A custom-developed MES or batch release engine with proprietary logic

- AI or algorithmic system making real-time product disposition decisions

- Heavily modified ERP modules where standard behavior has been overridden

- In-house developed laboratory or manufacturing control applications

Unlike Category 4 platforms, which are configured within defined supplier boundaries, Category 5 software typically requires validation down to the design and code level. There is no shortcut and no “the vendor is validated” excuse; full lifecycle assurance is expected.

In Category 5, regulators expect to see:

- Design-level traceability, not just URS and test protocols, but design specifications and code logic review

- Unit, integration, and functional testing — not only high-level OQ/PQ

- Clear definition of software development methodology (e.g., V-model or modern agile equivalent with proper control points)

- Security, override, and failure logic are intentionally tested, not assumed safe

- Active QA involvement throughout design and not just during final approval

This category demands accountability and transparency, not just paperwork. It is where validation and software engineering genuinely overlap, and anything that makes automated decisions without human verification is automatically treated at this level by regulators.

| Category | Description | Example in GMP | Validation Effort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cat.1: Infrastructure | OS, databases, servers | Windows Server | Installation only |

| Cat.3: Non-configured | Standard tools | Excel, simple LIMS | Light documentation |

| Cat.4: Configured | MES, eQMS | TrackWise | Medium-high effort |

| Cat.5: Custom code | Bespoke ERP, AI tools | AI Deviation Predictor | Full validation |

– Advertisement –

Why is Category 2 Not Included?

Category 2 originally appeared in very early GAMP versions as “firmware,” a category meant to describe fixed, embedded code inside hardware devices. As the guidance evolved, ISPE recognized that this distinction added no meaningful value to validation decision-making. Firmware could not be configured like Category 4 systems, nor could it be developed or modified like Category 5 applications.

At the same time, it required more assurance than a simple infrastructure component. In practice, it didn’t fit cleanly into any unique validation approach. With the release of GAMP 5, the category was formally retired and absorbed into the existing model.

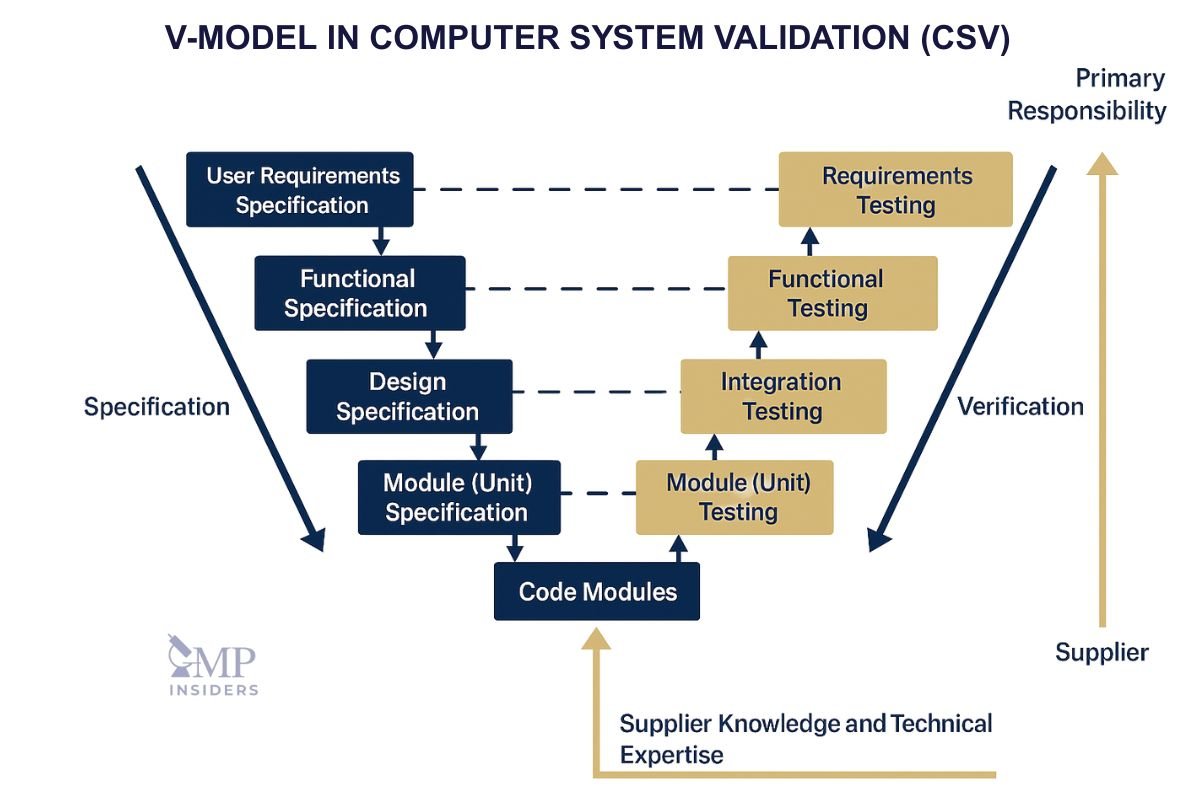

The V-Model in GAMP 5 and Its Modern Interpretation

The V-model has traditionally been associated with computerized system validation. Still, GAMP 5 makes it clear that it should be viewed as a conceptual illustration rather than a mandatory development lifecycle. Its purpose is to show the logical alignment between what is defined on the left side (requirements, design, configuration) and what is verified on the right side (testing and qualification).

The 2022 Second Edition reinforces this view: the V-model remains helpful for understanding traceability and lifecycle control, but it no longer dictates how systems must be delivered. Instead, GAMP 5 encourages organizations to apply the model with flexibility, critical thinking, and proportionality, especially in environments where agile, iterative, or supplier-driven development is the norm.

Purpose of the V-Model in the GAMP Context

The primary role of the V-model in GAMP 5 is to support understanding, not to prescribe a rigid sequence of activities. It visualizes how early decisions about intended use, requirements, and configuration must later be backed by evidence through qualification and testing.

This conceptual alignment helps avoid the common pitfall of validating systems without a clear connection between what was defined and what is being verified. In modern CSV execution, this model guides thinking rather than dictating procedure, ensuring that validation remains connected to risk and intended use rather than driven by templates or documentation volume.

A Conceptual Guide, Not a Strict Lifecycle

GAMP 5 explicitly states that the V-model is not a required software development methodology. Instead, it illustrates how assurance should be built from requirements through testing. This distinction is often misunderstood, especially in companies still applying legacy CSV approaches built around waterfall development.

GAMP 5’s interpretation emphasizes conceptual clarity rather than sequential execution, enabling teams to adapt the model to the realities of cloud services, SaaS platforms, and rapid release cycles.

The Importance of Traceability

Regardless of the delivery model, the V-model reinforces one core expectation: traceability. Each requirement must be linked to design or configuration decisions, and each of those must be mapped to corresponding verification activities.

See Also: Software Verification vs Validation in GMP

This is the foundation of defensible validation. Traceability ensures that the system you tested accurately reflects the system you intended to build, and this clarity is exactly what auditors expect.

The Left Side of the V-Model: Defining Intended Use

The left side of the V-model represents the structured definition of the system before testing begins. This is where intended use, business rules, and process risks are translated into requirements and configuration choices. GAMP 5 emphasizes that this definition must reflect the real GxP process and not simply mirror vendor capabilities. Misalignment here inevitably leads to over-testing, under-testing, or validation activities that add no value.

User Requirements Specification (URS)

URS defines what the system must achieve from a business and GxP perspective. Under GAMP 5, URS must be purposeful and written with risk in mind, not copied from a supplier brochure or generic template. It sets the foundation for all later qualification activities.

Functional and Configuration Specifications

Functional Specifications (FS) and Configuration/Design Specifications (CS/DS) translate the URS into operational logic. They define how workflows, decision logic, calculations, and data rules will be executed within the system. These specifications enable clear traceability to later testing and reduce ambiguity during qualification.

Early Risk Assessment

GAMP 5 requires that risk assessment begin here, before testing, not during or after. Early risk-based decisions define the scope of testing and prevent unnecessary qualification activities. The model encourages targeted focus on functions that impact product quality, patient safety, or data integrity.

The Right Side of the V — Model: Verifying System Control

The right side of the V represents the evidence-gathering phase, during which the system is proven fit for its intended use. These qualification activities must be aligned with the specifications defined earlier. GAMP 5 strongly emphasizes that testing should be risk-based and relevant, avoiding traditional “test everything” approaches that inflate documentation without improving system assurance.

Installation Qualification (IQ)

IQ verifies that the technical foundation—hardware, environment, platform, and configuration—has been correctly installed, hardened, and secured. This step ensures that the infrastructure supporting the application cannot compromise the application’s validated functionality.

Operational Qualification (OQ)

OQ focuses on verifying the configured functionality, business rules, calculations, and interfaces. Only risk-relevant functions are tested, reflecting the link to earlier specifications rather than exhausting every vendor capability.

Performance Qualification (PQ)

PQ tests the system in real business scenarios to confirm that it consistently supports the intended process. GAMP 5 positions PQ as the culmination of the model—evidence that the system performs reliably within the regulated environment it was designed for.

How GAMP 5 Second Edition Modernizes the V-Model

The Second Edition acknowledges that modern systems no longer fit neatly into sequential waterfall patterns. SaaS, cloud-hosted platforms, configurable enterprise systems, and continuous updates require iterative and flexible validation approaches. Rather than discarding the V-model, GAMP 5 reframes it as a logical mapping tool applicable to any delivery method.

Alignment with Agile and Iterative Development

Agile, DevOps, and CI/CD methods are fully compatible with GAMP 5, provided the organization maintains clear traceability and risk-based justification. Requirements, configuration decisions, and testing outputs may evolve iteratively—but traceability links must remain intact.

Focus on Critical Thinking and Proportionality

The updated model discourages over-documentation and procedural repetition. Instead, it demands that each validation activity be justified, meaningful, and directly linked to risk. The V-model supports this by maintaining logical structure without imposing unnecessary constraints.

Integration with Supplier-Driven Lifecycles

Modern systems, especially SaaS and cloud solutions, involve ongoing supplier activities that replace parts of the traditional V-model. GAMP 5 recognizes this shift and expects regulated companies to leverage supplier evidence rather than duplicate testing.

Practical Application of GAMP 5 in Pharma

GAMP 5 is not something that sits beside CSV. It is the thinking model that defines how CSV should be executed correctly. When applied as intended, it ensures that validation is not only compliant on day one but also remains defensible throughout the system’s full lifecycle.

Where GAMP 5 Fits in the CSV Lifecycle

GAMP 5 integrates directly into the CSV workflow from the very beginning. It influences how User Requirements are written, how validation effort is scaled during qualification, and how control is maintained after go live. It prevents CSV from being treated as a one-time checklist exercise and positions it as a continuously justified state of assurance.

In a mature CSV approach based on GAMP 5 thinking:

- The URS is driven by intended use and risk, not copied features from a vendor brochure

- Validation focuses on demonstrating controlled use of the system, not generic functional completeness

- The system remains validated only if change control, periodic review, and data governance remain active over time

This is the point at which many companies fail; they validate for go-live, not for sustained control.

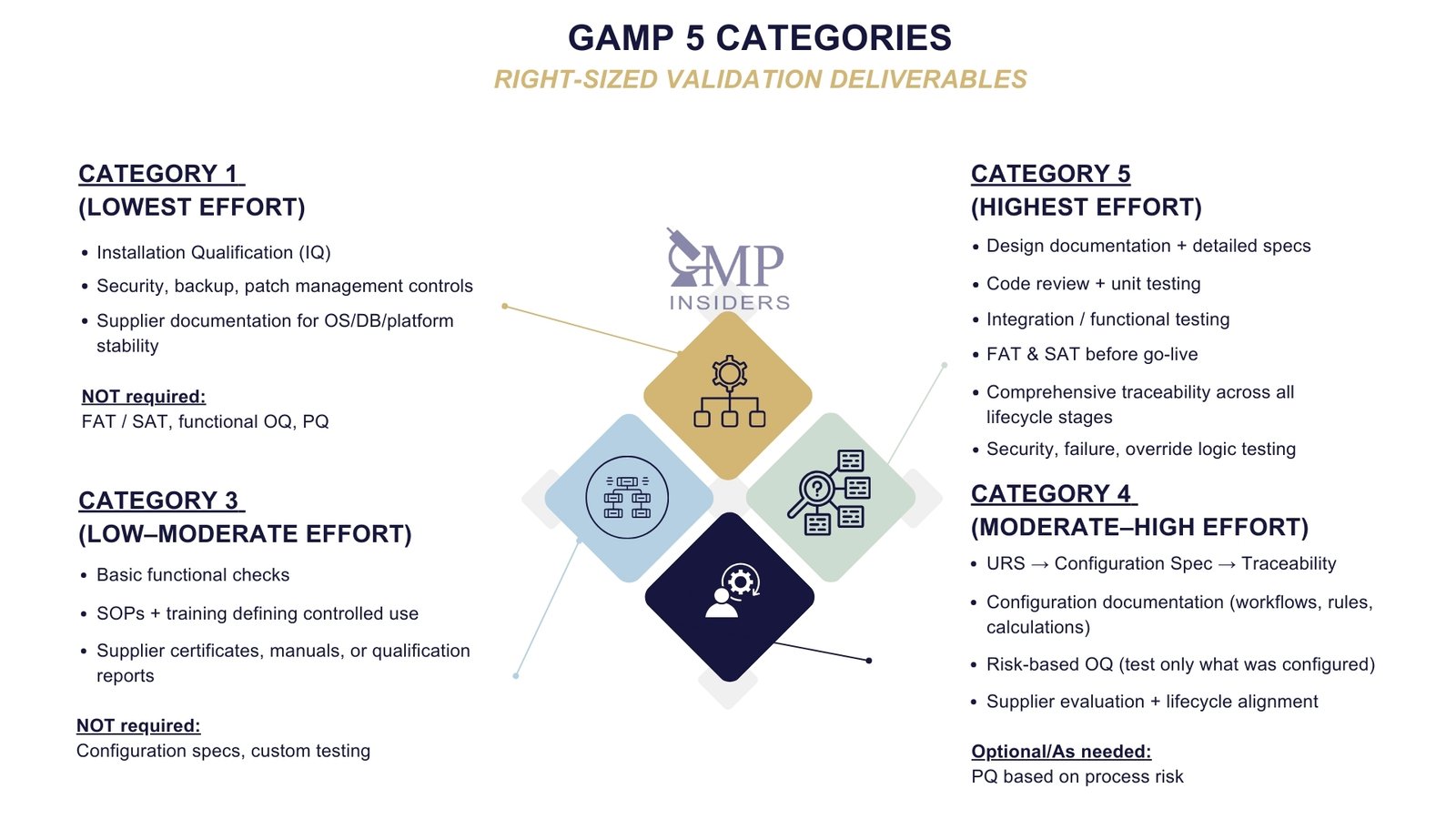

Deliverables Required per GAMP Category

One of the most practical benefits of GAMP 5 is that it prevents companies from imposing the same validation burden on every system. The category does not determine compliance level. It determines how much evidence is required, who provides it, and how deeply you must test.

For example, Category 1 and 3 systems do not require FAT or SAT, because they have no custom logic or configuration that needs to be verified before operational use. In contrast, Category 4 and 5 systems absolutely do, as configuration or custom code directly influences decision logic and therefore GxP risk.

In practice, right-sizing the deliverables looks like this:

- Category 1: Infrastructure qualification only. Focus on installation, security, backup, and patch control.

- Category 3: Intended use confirmation and procedural control. Supplier evidence is leveraged where appropriate.

- Category 4: Configuration documentation, traceability, and risk-based OQ. The majority of pharma validation sits here.

- Category 5: Full lifecycle control, including design documentation, code review, unit testing, and formal FAT/SAT before deployment.

The key point is that GAMP does not reduce validation effort. It optimizes it, ensuring evidence is proportionate to risk, not habit.

To ensure this effort translates into actual regulatory compliance, it must align with global expectation not just internal interpretation.

Alignment with Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11

GAMP 5 is fully aligned with both EMA Annex 11 and FDA 21 CFR Part 11. These regulations do not prescribe how to validate systems; they simply require that systems be validated, controlled, and capable of protecting electronic records throughout their operational life. GAMP provides the practical interpretation to achieve that expectation without unnecessary complexity.

| Requirement | Annex 11 Emphasis | 21 CFR Part 11 Emphasis | GAMP Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation | Lifecycle control | Reliable systems | Methodology |

| Records | Data lifecycle | Security | Interpretation |

| Access | User control | Authorization | Role design |

| Audit Trail | Mandatory | Integrity focus | Testing/Review |

Annex 11 expects:

- A validated system that remains in a state of control throughout its lifecycle

- Clear supplier involvement and documented evaluation during selection

- Ongoing data integrity assurance, not just validation at go-live

- Controlled change management, access security, audit trail review, and periodic evaluation of system suitability

21 CFR Part 11 focuses on:

- Trustworthiness of electronic records and electronic signatures

- Ability to detect and prevent unauthorized data changes

- Secure, controlled retention and retrieval of records for regulatory access

GAMP 5 satisfies both by ensuring that validation is not only present but proportionate, traceable, and actively maintained over time. This is why inspectors increasingly look less at how many documents exist and more at whether the company can prove control over how the system operates today.

SEE ALSO: Annex 11 vs 21 CFR Part 11: Detailed Comparison

GAMP 5 and CSA

GAMP 5 does not conflict with CSV or CSA. In fact, it is the framework that ensures CSV is applied correctly. Traditional CSV has always required a risk-based approach and proof of fitness for intended use. Still, many companies implemented it in a purely document-driven way, generating volume rather than assurance.

This is why the FDA introduced CSA. It is not a new regulatory requirement, but a clarification of intent. CSA does not replace CSV, it reinforces how CSV should have been applied from the beginning. It challenges excessive testing and unnecessary documentation that offer no risk reduction, and encourages effort to be focused where decisions or data integrity are actually impacted.

GAMP 5 is already aligned with this philosophy. A company applying GAMP 5 correctly is, by definition, already aligned with CSA expectations without needing to “transition” or overhaul its validation model. CSA is simply the FDA confirming that risk-based critical thinking is not optional.

GAMP 5 Certification & Training

There is no globally recognized or mandatory GAMP 5 certification issued by any regulatory authority. Health agencies such as EMA, FDA, MHRA, or WHO do not require individuals or companies to hold a GAMP certificate. Compliance is measured by how well GAMP principles are applied in practice, not by whether someone has attended a course.

What is commonly misunderstood

- GAMP 5 is guidance, not a formal standard like ISO.

- There is no official or regulator-issued GAMP license or certification.

- Companies cannot “be GAMP-certified”,they can only be GMP-compliant and GxP audit-ready.

Industry reality

- ISPE provides official GAMP training, and it is globally respected, but not legally required.

- Auditors do not ask for personal GAMP certificates; they assess understanding and execution of GAMP principles.

- However, during vendor qualification or partner evaluation, some companies may view ISPE GAMP training as a positive indicator of competence, especially for CSV and QA roles.

Bottom line:

GAMP certification is not mandatory, but being able to demonstrate practical mastery of GAMP principles absolutely is, especially in regulated audits and system validation leadership roles.

GAMP 5 vs Annex 11 vs FDA CSA

GAMP 5, Annex 11, and FDA CSA are not competing frameworks. They address different aspects of the same expectation: a computerized system must be fit for use, controlled throughout its lifecycle, and capable of protecting data integrity. The difference lies in their role and how they guide your actions during CSV.

| Framework | Type | Role | Focus | Relation to CSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAMP 5 | Guidance (ISPE) | Practical methodology | Risk-based lifecycle, intended use | How to execute CSV correctly |

| Annex 11 | Regulation (EU GMP) | Compliance requirement | Validation, data integrity, control | What CSV must achieve |

| FDA CSA | FDA Guidance Clarification | Optimization of execution | Risk-based assurance, efficiency | How CSV should be applied in practice |

– Advertisement –

FAQ

How Does GAMP 5 Address Cybersecurity Risks in Validated Systems?

While GAMP 5 is not a cybersecurity standard, it explicitly reinforces the need for controlled access, secure architecture, and protection against unauthorized data manipulation. Cyber risk is treated as part of validation risk assessment, particularly when external connectivity or cloud-hosted environments are involved.

The Second Edition emphasizes IT/OT convergence and supplier security review more clearly. GAMP aligns well with the NIST and ISO 27001 frameworks but maintains a focus on data integrity and GxP continuity.

Is GAMP 5 Applicable to AI and Machine Learning Systems Used in GxP processes?

Yes, the GAMP 5 Second Edition explicitly acknowledges AI and ML use cases. It requires that systems with adaptive or learning behavior must have defined control boundaries, human oversight, and documented decision explainability.

Validation must account for performance drift, not just initial qualification. These systems are generally treated as Category 5 due to their autonomous decision-making impact potential.

Is Vendor Audit Mandatory Under GAMP 5 Before Selecting a System?

GAMP 5 does not require physical audits of every vendor but expects proportional supplier evaluation based on system criticality. For low-risk Category 1 or 3 systems, a documented paper-based assessment may be sufficient. For SaaS, MES, and LIMS systems involved in product release or batch execution, a formal supplier audit is strongly recommended. Regulators expect justification — not blind trust in vendor claims.

Can a GAMP 5-Validated System Be Downgraded or Re-Categorized Later?

Yes, but any category change must be risk-justified and properly documented, not done retroactively to reduce effort. If the system’s configuration, use case, or regulatory impact changes over time, its GAMP category should be reassessed. GAMP 5 supports lifecycle re-evaluation rather than frozen classifications. Regulators will expect traceable reasoning behind the change, not silent modification of validation status.

How Does Gamp 5 Treat Cloud-Hosted SAAS Platforms Differently From On-Premise Systems?

GAMP 5 does not favor on-premise or cloud environments; it requires evidence of control regardless of the hosting model. However, with SaaS, supplier assessment, contractual SLAs, and transparency around updates and changes become critical. You do not test what the supplier should already control; you must prove fitness for your specific intended use and maintain continuous oversight. Annex 11 and the FDA both now expect documented governance over cloud providers.

Does GAMP 5 Require a V-Model Validation Approach, or Can Agile Be Used?

GAMP 5 does not mandate the traditional V-model; it explicitly permits agile and iterative development, provided risk and control are demonstrably managed. The critical requirement is traceability and decision justification, not adherence to a specific development model. The Second Edition strongly acknowledges modern delivery models such as DevOps, CI/CD, and modular validation. Agile does not reduce validation; it changes how and when controls are applied.

How Often Should a Validated GAMP 5 System Undergo Periodic Review?

GAMP 5 does not define a fixed timeline. Periodic review frequency is expected to be risk-based and proportional to system criticality and change frequency. Critical GMP systems may require annual review, while low-impact tools may qualify for longer intervals. The key point is that “no change made” is not accepted as proof of ongoing control unless recorded in structured review.

Final Thoughts

GAMP 5 is not a documentation framework. It is a way of thinking about computerized systems in a regulated environment. Companies that still approach validation as a one-time compliance event eventually lose control the moment the system goes live. Regulators are no longer focused on the size of validation binders but on whether the system is demonstrably in a continuously controlled, risk-justified, and process-relevant state.

When applied correctly, GAMP 5 does more than support audit readiness. It enables faster and more sustainable digital implementation while maintaining regulatory integrity. The question is no longer whether a system has been validated but whether it remains fit for purpose, defensible at any time, and capable of scaling with future business and regulatory evolution.

Disclaimer: This article includes advertisement placements in collaboration with Validify. The editorial content was created independently by GMP Insiders.