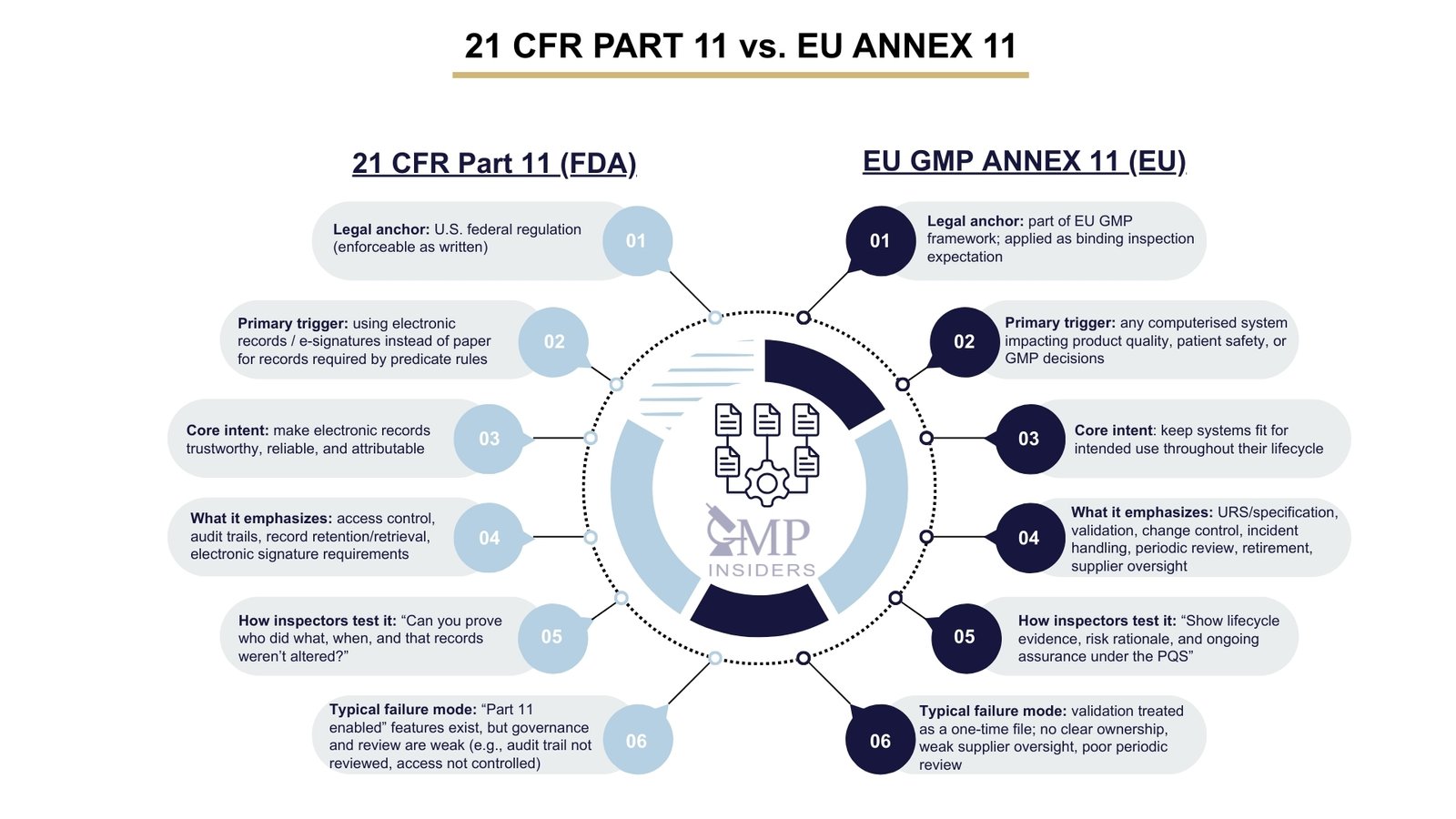

Electronic records and computerized systems are expected to be controlled, reliable, and defensible, with clear evidence that they support compliant operations. In this context, FDA 21 CFR Part 11 and EU GMP Annex 11 are among the most frequently cited documents for defining expectations for validation, data integrity, governance, and oversight of systems that handle GMP-relevant data.

They are frequently compared, yet they are not equivalent frameworks. They are grounded in different legal bases, address different scopes, and are applied differently across inspections, yet many organisations must operate in accordance with both.

21 CFR Part 11 establishes legally binding requirements for electronic records and electronic signatures to be considered trustworthy, secure, and attributable. Annex 11, positioned within the EU GMP framework, extends beyond records and signatures to the complete lifecycle of computerized systems. It sets expectations regarding the validation strategy, documented risk management, supplier control, system governance, and the ongoing assurance that systems remain fit for their intended use.

This article provides a clear, practice-focused comparison of Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11, exploring scope, legal status, lifecycle expectations, audit trail requirements, risk management, supplier oversight, and how authorities typically challenge weaknesses in real situations. The objective is not simply to highlight differences, but to define a coherent compliance approach that supports both frameworks and remains robust during inspections.

What is 21 CFR Part 11?

21 CFR Part 11 is a legally binding U.S. regulation issued by the Food and Drug Administration that defines the conditions under which electronic records and electronic signatures are accepted as equivalent to paper records and handwritten signatures. Its core purpose is to ensure that electronic records used to demonstrate compliance are trustworthy, reliable, and able to withstand review.

Part 11 applies to records created, modified, maintained, archived, retrieved, or transmitted in electronic form when those records are required by predicate rules (e.g., 21 CFR Parts 210–211, 820, 600 series). It also applies to the use of electronic signatures intended to replace handwritten signatures.

When organizations choose to manage records electronically, they are expected to implement defined controls that provide confidence in the authenticity, integrity, and attribution of records.

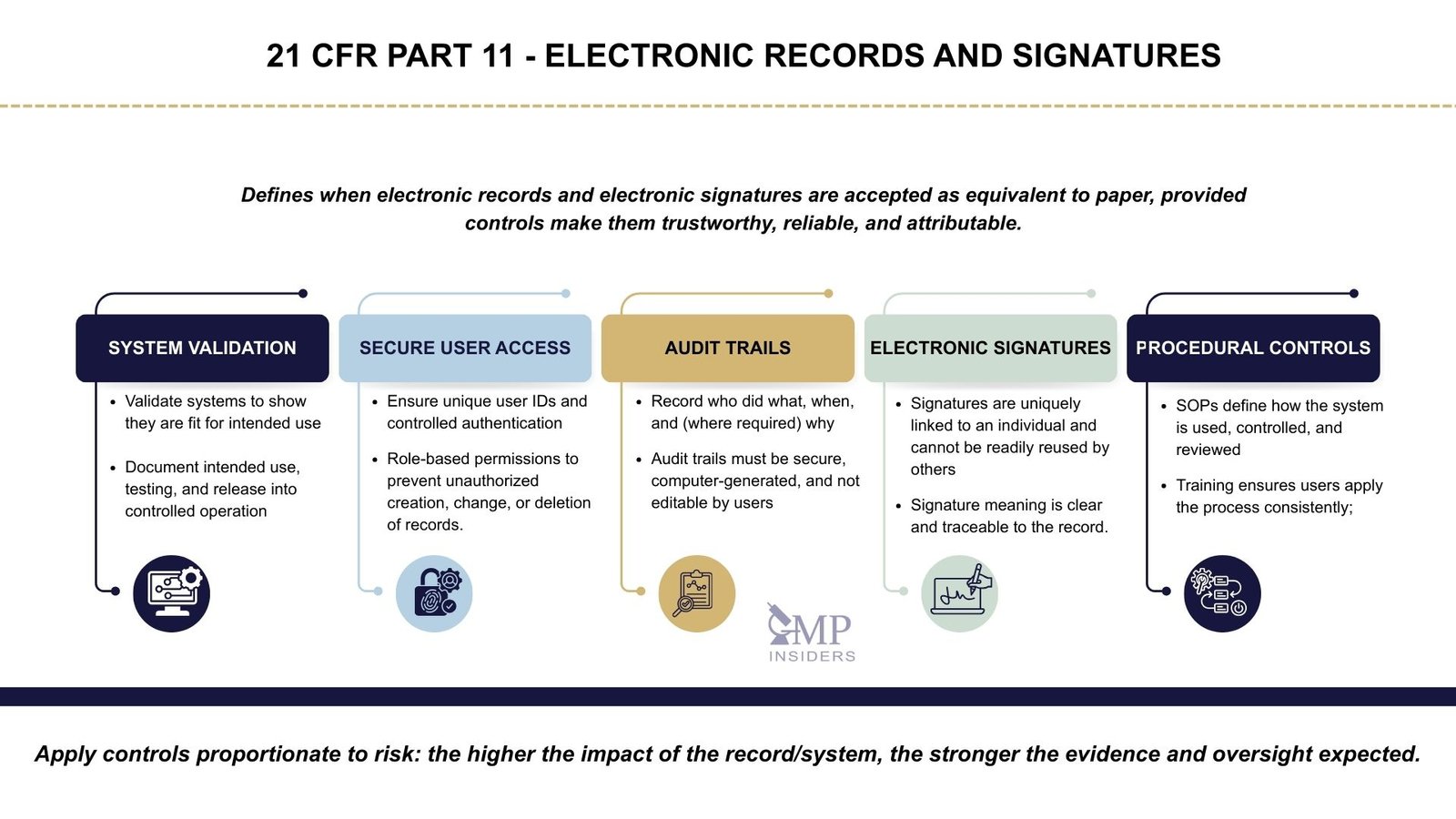

At a practical level, Part 11 establishes expectations in key areas such as:

- System validation to demonstrate fitness for intended use.

- Secure user access and authority management to prevent unauthorised activities.

- Audit trails to document who performed what action, when, and why, without allowing manipulation.

- Electronic signatures that are uniquely linked to an individual and legally enforceable.

- Procedural controls, including policies, training, and documented governance of system use.

Although the regulation is concise, its application is supported by additional FDA guidance that explains enforcement intent, risk-based considerations, and acceptable approaches to compliance.

Organisations are expected to adopt controls that are proportionate to the system’s impact and the criticality of the records managed, and to maintain demonstrable evidence of control when records are reviewed.

What is EU GMP Annex 11?

EudraLex GMP Annex 11 sets out expectations for the management of computerized systems used to support GMP activities. Unlike 21 CFR Part 11, which is explicitly focused on electronic records and electronic signatures, Annex 11 adopts a broader lifecycle approach, covering how systems are specified, developed, or configured, validated, implemented, maintained, and retired, while ensuring that they remain fit for intended use throughout their operational life.

Annex 11 applies to any computerized system that has an impact on product quality or patient safety, or is used to demonstrate compliance with GMP requirements. This includes systems used in manufacturing, quality control laboratories, quality assurance, and the support of quality system processes.

The expectation is not only that systems are technically capable, but that they are governed within a structured pharmaceutical quality system and supported by appropriate procedural, technical, and organisational controls.

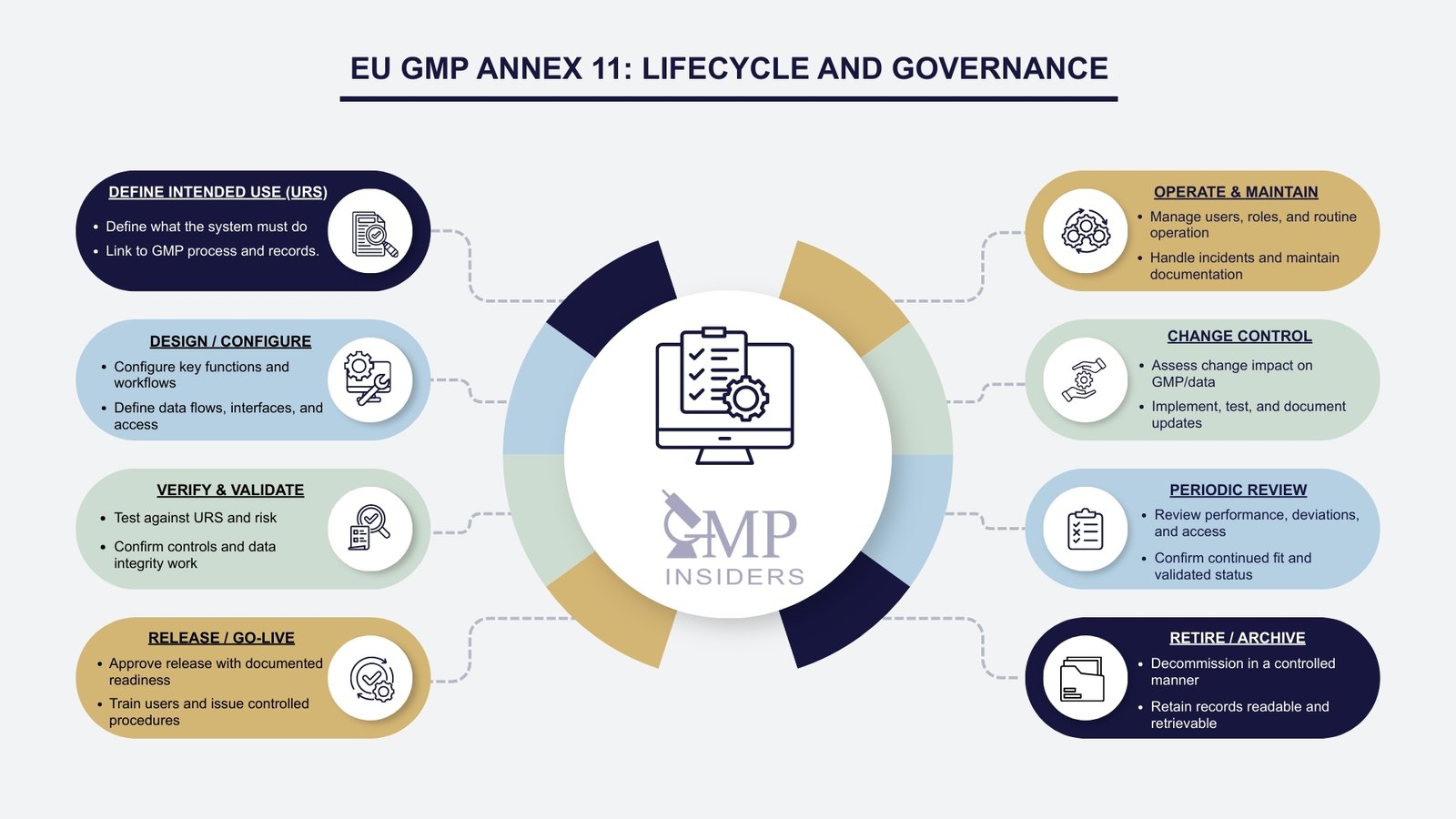

Key expectations under Annex 11 include:

- A defined system lifecycle approach, supported by documented requirements, design, verification, validation, and controlled change management.

- Documented and demonstrable risk management, applied throughout the lifecycle to justify the type and extent of controls implemented.

- Clear assignment of responsibilities, including system ownership, process ownership, and vendor responsibilities where applicable.

- Supplier and service provider oversight, recognising that outsourcing does not transfer responsibility for compliance.

- Data integrity and data governance controls ensure that records remain complete, consistent, attributable, and available throughout their retention period.

- Ongoing assurance, including periodic review, incident management, deviation handling, backup, disaster recovery, and continued validation status.

Annex 11 is part of the legally enforceable EU GMP framework. Although structured as guidance, it is routinely applied in inspections, and non-compliance with its principles is treated as a GMP deficiency.

As such, authorities expect organisations to demonstrate a logical, risk-based, and well-documented approach to the management, governance, and verification of computerized systems to support compliant operation.

Draft Annex 11 Revision (2025) — Key Updates

In July 2025, the European Commission and PIC/S published a draft revision of EU GMP Annex 11 “Computerised Systems” for stakeholder comment. The draft significantly expands and restructures the 2011 version, reflecting modern digital realities and aligning more closely with global expectations for system assurance.

Key characteristics of the Draft Annex 11:

- Expanded to around 19 sections with a detailed glossary.

- Structured around lifecycle topics, including security, identity/access management, audit trails, supplier management, validation/qualification, periodic review, and other areas relevant to system assurance.

- Clear emphasis on risk management, security, and lifecycle governance throughout.

- Reflects contemporary technological contexts, including cloud computing, SaaS platforms, AI, and advanced service provider models.

The draft is currently in consultation phase with comments open (until October 7, 2025), and a final version is expected to be published in 2026.

Practical implication: The revised Annex 11 is moving toward a more explicit, structured, and prescriptive set of expectations for computerized systems, reducing ambiguity in areas such as access control, security, and audit trail review.

| Item | Key point |

|---|---|

| What it is | Draft revision of EU GMP Annex 11 (“Computerised Systems”). |

| Published | July 2025 (European Commission + PIC/S) for comment. |

| What changed | Expanded and restructured vs 2011; ~19 sections + glossary. |

| Main focus | Lifecycle assurance: security, access, audit trails, suppliers, validation, periodic review; risk-based governance. |

| Tech scope | Covers cloud/SaaS, AI, modern service models. |

| Status & timing | Consultation open until Oct 7, 2025; final expected in 2026. |

| Why it matters | More explicit and prescriptive expectations; less ambiguity (access, security, audit trail review). |

Annex 11 vs 21 CFR Part 11

Before proceeding point by point, it is essential to note that the two documents do not occupy the same legal position, serve the same purpose, or are applied in the same way in practice. The following sections examine the key areas in which organisations most frequently misinterpret alignment and where inspectors typically expect clarity and structure.

| Requirement Area | EU GMP Annex 11 | FDA 21 CFR Part 11 | Practical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Position | Part of EU GMP; applied as enforceable expectation in inspections. | Legally binding federal regulation. | Both are effectively mandatory where applicable; enforcement route differs. |

| Primary Focus | Governance and lifecycle of computerized systems. | Trustworthiness of electronic records and electronic signatures. | Annex 11 = system control; Part 11 = record control. Both must coexist. |

| Scope | All computerized systems supporting GMP-relevant activities. | Electronic records, signatures, and submissions used in place of paper. | Annex 11 covers more systems explicitly; Part 11 is narrower but strict. |

| Lifecycle Management | Explicit lifecycle expectations including specification, validation, change control, periodic review. | Requires validation; lifecycle discipline inferred through general GMP expectations. | Annex 11 explicitly structured; Part 11 depends more on interpretation and supporting frameworks. |

| Validation | Risk-based lifecycle validation proportionate to impact and complexity. | Validation required to ensure accuracy, reliability, and consistent performance. | Annex 11 forces lifecycle thinking; Part 11 expects equivalent outcome. |

| Risk Management | Explicit requirement, applied across the lifecycle. | Expected implicitly through FDA and GMP expectations, not explicitly written in Part 11. | Annex 11 makes risk assessment highly visible and auditable. |

| Audit Trails | Required where appropriate based on risk and criticality; expected to be reviewed. | Mandatory, prescriptive audit trail controls for electronic records. | Part 11 is more explicit; Annex 11 embeds audit trail control into data governance. |

| Electronic Signatures | Required to be attributable and controlled, but less prescriptive in mechanics. | Highly prescriptive; unique, verifiable, and legally binding equivalence defined. | Organisations must meet Part 11’s higher specificity when signatures are used. |

| Data Integrity | Embedded throughout Annex 11 with lifecycle and governance emphasis. | Strongly enforced through Part 11 + predicate rules + guidance. | Both expect complete, consistent, attributable, secure, retained records. |

| Supplier & SaaS Oversight | Explicit requirement for supplier qualification, contracts, and accountability. | Responsibility remains with regulated company; oversight implied through GMP. | Annex 11 gives authorities direct leverage to challenge weak vendor control. |

| Documentation & QMS Integration | Strong emphasis on integration into pharmaceutical quality system. | Requires procedural and documentary controls but less explicit about QMS structure. | Annex 11 demands visible governance; FDA still expects structured documentation. |

| Legacy/Hybrid Systems | Allowed with documented justification and compensating controls. | Allowed with documented justification and compensating controls. | Both tolerate legacy/hybrid use but expect risk-based controls and evidence. |

| Inspection Behaviour | Authorities challenge lifecycle discipline, risk management, vendor control, and governance. | Authorities challenge record integrity, audit trails, access control, validation weakness. | Themes overlap; angles differ. Mature systems withstand both perspectives. |

Legal Nature and Position in the Framework

The first and most fundamental distinction lies in the way each document exists within its respective regulatory framework. This influences how authorities interpret them, how obligations are derived, and what “non-compliance” means in practice during inspections.

21 CFR Part 11

- U.S. federal regulation issued by FDA.

- Applies where electronic records/electronic signatures are used in place of records/signatures required by predicate rules (e.g. 21 CFR 210, 211, 820).

- Non-compliance can be cited directly in enforcement actions, including warning letters and import alerts.

Annex 11

- Part of the EU GMP framework, sitting alongside other Annexes and Chapters.

- Not a standalone law, but applied as a binding expectation during inspections; failures are written as GMP deficiencies.

- Closely read in combination with EU GMP Chapter 1 (Pharmaceutical Quality System) and Chapter 4 (Documentation), plus Annex 15 (Qualification and Validation).

Practical consequence: Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 are effectively mandatory in the markets to which they apply. The difference lies in how they are embedded: Part 11 is embedded in predicate rules; Annex 11 is embedded within the GMP system itself.

Scope: What Each Document Actually Covers

Once the legal positioning is understood, the next critical distinction is scope. Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 do not apply to the same range of systems or records, and many implementation errors come from assuming that both documents “cover everything” in the same way.

Understanding exactly what each framework intends to control is essential before translating requirements into practice.

21 CFR Part 11

- Scope is electronic records, electronic signatures, and electronic submissions.

- Does not explicitly attempt to govern every computerized system; its focus is on records that demonstrate compliance with FDA predicate rules.

- Paper or hybrid approaches may fall partially outside Part 11, but the underlying GMP/PQ requirements still apply.

Annex 11

- Scope encompasses all computerized systems used in GMP activities.

- Includes systems that generate, process, store, or retrieve data that may have an impact on product quality or on decisions made within the quality system.

- Even systems without formal electronic signatures or “official records” may fall under Annex 11 if their outputs influence GMP decisions.

Practical consequence: Annex 11 has a broader scope, with more systems explicitly falling within its expectations. Part 11 is narrower but interacts with broader GMP expectations. A system that may sit outside Part 11 can still be fully in scope for Annex 11.

Structural and Conceptual Focus

Beyond legal positioning and scope, Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 also differ conceptually in their structure. Each document is built around a different primary intent, which directly influences how organisations interpret requirements and how inspectors evaluate implementation.

Understanding this underlying philosophy is essential; otherwise, compliance efforts risk being either too narrow or poorly aligned with expectations.

21 CFR Part 11

- Structured around specific topics: controls for closed/open systems, electronic signatures, signature/record linking, etc.

- Conceptual focus is: “If you want electronic records/signatures to replace paper, these are the minimum controls.”

- Lifecycle, governance, and risk are implicit and addressed through predicate rules and general GMP expectations, rather than through Part 11 wording itself.

Annex 11

- Structured as GMP expectations for computerized system lifecycle control.

- Emphasises specification, design, verification/validation, change control, incident handling, periodic review, and retirement.

- Conceptual focus is: “Computerized systems must be managed like any other GMP-relevant element, with defined lifecycle and risk-based controls.”

Practical consequence: Annex 11 is naturally read in a lifecycle/GAMP context; Part 11 needs to be interpreted together with predicate rules and FDA guidance to reach the same depth.

Validation and Lifecycle Management

Once scope and structural intent are understood, the next critical difference lies in how each framework approaches validation and ongoing system control. This is one of the areas most frequently challenged during inspections, particularly where organisations treat validation as a one-time technical exercise rather than an ongoing, lifecycle-driven obligation. The two documents align in principle, but they express expectations in very different ways.

21 CFR Part 11

- Requires systems to be validated to ensure accuracy, reliability, consistent intended performance, and the ability to discern invalid/altered records.

- Does not prescribe a lifecycle model, documentation set, or specific methodology.

- FDA expects risk-based validation; supporting detail usually comes from industry practice (e.g. GAMP 5) and predicate rules.

Annex 11

- Explicitly requires a defined lifecycle: documented user requirements, design, verification, validation, controlled changes, and periodic review.

- Expects validation to be proportionate to risk and complexity, and to be supported by risk management.

- Links lifecycle expectations directly to the pharmaceutical quality system (e.g. deviation/CAPA handling, qualification of suppliers, configuration control).

Practical consequence: If you implement Annex 11 thoughtfully, you usually cover Part 11 validation expectations automatically. The reverse is not guaranteed: “Part 11 validation” done in isolation can be too narrow if lifecycle and governance elements are missing.

Audit Trails and Data Integrity Controls

Audit trails and data integrity controls are among the most visible and frequently inspected elements when authorities evaluate electronic records and computerized systems. Both Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 address traceability, attribution, and protection against unauthorised change, but they approach these requirements with different levels of prescriptiveness and different emphases on risk, review, and governance.

21 CFR Part 11

- Requires secure, computer-generated, time-stamped audit trails for creation, modification, and deletion of electronic records.

- Audit trails must be retained as long as the records themselves and must be available for review and copying.

- The emphasis is on traceability of who did what and when, and on the integrity of the record history.

Annex 11

- Requires audit trails where necessary to support GMP decisions and data integrity, based on a documented risk assessment.

- Audit trail review is expected as part of routine use, especially for critical records.

- Discusses data integrity more broadly: accuracy, completeness, consistency, and protection against unauthorised change.

Practical consequence: Part 11 is more explicit and prescriptive regarding audit trails, whereas Annex 11 embeds audit-trail expectations within a broader data governance model. Many inspection findings arise when companies claim “risk-based exclusion” of audit trails without a defensible rationale.

Electronic Signatures

Electronic signatures are another key area in which Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 align in principle but differ in the degree to which they define expectations. Both frameworks require that signatures clearly identify the individual, demonstrate intent, and be permanently linked to the associated record.

However, the levels of prescriptive detail, legal framing, and expectations for supporting documentation differ, directly influencing how organisations design and justify their controls.

21 CFR Part 11

- Formal requirements for electronic signatures:

- Must be unique to one individual.

- Must be verifiable and linked to their records.

- Must use at least two distinct components (e.g. ID + password) for signings.

- Binding equivalence to handwritten signatures is explicitly stated.

- Signature manifests (meaning, intent, and context) must be clear in the record.

Annex 11

- Addresses electronic signatures more briefly, aligned with EU expectations.

- The focus is on identification, attribution, and control rather than on detailed signature mechanics.

- Often applied together with Chapter 4 and local legal requirements for electronic signatures.

Practical consequence: For Annex 11 vs 21 CFR Part 11, Part 11 gives more explicit criteria for signatures. Annex 11 expects equivalent assurance but delegates more detail to GMP documentation, local law, and system design.

Risk Management and Criticality

A major distinguishing feature between Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 is the extent to which they explicitly address risk. Both expect controls to be proportionate to the system’s impact and the criticality of the data handled, but they express this expectation differently.

Annex 11 embeds risk management directly into the lifecycle, while Part 11 relies on broader FDA and GMP expectations to drive a risk-based approach. This difference is often reflected in inspection outcomes, particularly where organisations cannot demonstrate structured, documented decision-making.

21 CFR Part 11

- Does not explicitly describe formal risk management, but FDA expects a risk-based approach.

- Enforcement and guidance make clear that control depth should align with impact on product quality and patient safety.

- Risk management elements are usually drawn from more general quality risk management frameworks (e.g. ICH Q9).

Annex 11

- Explicitly requires documented risk management across the lifecycle.

- Risk is used to:

- Classify systems.

- Determine validation depth.

- Decide where audit trails, redundancy, and controls are required.

- Expects risk management to be integrated with the overall pharmaceutical quality system.

Practical consequence: Annex 11 makes risk management visible and auditable; authorities will ask for risk assessments. Under Part 11, risk is still expected, but the basis is more inferred from overall FDA and ICH expectations.

SEE ALSO: Quality Risk Management in Computer System Validation (CSV)

Supplier, Service Provider, and SaaS Oversight

Another clear point of divergence between Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 is their approach to suppliers, service providers, and externally hosted or cloud-based solutions.

Both frameworks recognise that organisations increasingly rely on third parties, but they differ in how explicitly they articulate expectations for oversight. This is a frequent focus of inspections, particularly when companies assume that vendor competence replaces internal responsibility.

21 CFR Part 11

- Vendors are not regulated entities under Part 11; responsibility remains with the regulated company.

- Vendor documentation can be leveraged, but cannot replace user validation and governance.

- Oversight expectations are derived from general GMP and quality system requirements, not from Part 11 alone.

Annex 11

- Explicitly addresses supplier and service provider management.

- Requires formal assessment, qualification, and written agreements defining responsibilities (e.g. for cloud services, hosting, support, maintenance).

- Outsourcing does not transfer responsibility for compliance; users remain accountable for how systems are used and controlled.

Practical consequence: Annex 11 provides inspectors with a direct means to challenge weak vendor control. For Part 11, the same expectation exists but is enforced via general GMP and quality system deficiencies.

Documentation, Governance, and Integration into the QMS

Beyond technical controls, both Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 depend heavily on the governance of computerized systems through documented procedures, defined responsibilities, and integration into the wider pharmaceutical quality system.

This is where inspectors often distinguish between organisations that “implemented a system” and those that can demonstrate sustained, managed control. The two documents approach this area differently in terms of explicitness and depth, which, in turn, influences how authorities evaluate compliance.

21 CFR Part 11

- Requires procedures for system use, security, change control, record retention, signature controls, etc.

- Does not prescribe a full documentation set, but the FDA expects:

- Validation documentation.

- SOPs and work instructions.

- Training records.

- Access management records and configuration control evidence.

Annex 11

- Assumes and reinforces that computerized systems are managed through the pharmaceutical quality system.

- Expects clear definition of:

- System owner, process owner, and responsibilities.

- Change control, deviation handling, CAPA, periodic review, backup/restore.

- Interfaces to other QMS elements (complaints, batch release, data integrity investigations).

Practical consequence: Annex 11 is more explicit about integration into the QMS. Pure “IT-driven” approaches with minimal QA ownership are highly vulnerable under Annex 11 and increasingly challenged in Part 11 contexts as well.

Legacy Systems, Hybrid Records, and Workarounds

Legacy platforms, partially electronic environments, and hybrid arrangements remain common in practice and are frequently examined during inspections because they introduce additional risks to data integrity and control.

Neither Annex 11 nor 21 CFR Part 11 requires organisations to replace every older or non-integrated system immediately, but both expect that risks are clearly understood, formally assessed, and appropriately controlled. How each framework addresses these situations varies slightly in emphasis and wording, but the expectation remains the same: continued use must be justified and managed demonstrably.

21 CFR Part 11

- FDA guidance recognises legacy and hybrid systems but expects control measures to mitigate risks:

- Documented rationale for retained use.

- Compensating controls (e.g. procedural checks, manual reconciliation).

- Hybrid systems (paper + electronic) are often a focus area during FDA reviews.

Annex 11

- Expects that legacy systems and hybrid arrangements are assessed, controlled, and justified via risk management.

- Compensating controls must be defined, documented, and verified to be effective.

- Manual interventions and external calculations are often treated as critical and subject to data integrity review.

Practical consequence: Both frameworks tolerate legacy/hybrid approaches, but only where risk is clearly understood and controlled. Uncontrolled spreadsheets, manual transcription, and undocumented workarounds remain frequent findings under both.

Inspection and Enforcement Patterns

While Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 differ in wording, structure, and emphasis, their practical impact is most clearly seen in how authorities inspect against them. Inspection behaviour demonstrates how regulators actually interpret requirements, which areas they prioritise, and where organisations most commonly fail.

The patterns are consistent: deficiencies rarely arise from misunderstandings of terminology but from weak governance, inadequate validation discipline, and insufficient control over data and system use.

21 CFR Part 11

- Typical FDA concerns include:

- Lack of validation evidence.

- Disabled or incomplete audit trails.

- Shared user accounts and weak access control.

- Inadequate backup/restore and disaster recovery testing.

- Inability to reconstruct who did what, when.

Annex 11

- Typical EU GMP findings include:

- No documented lifecycle or risk-based validation approach.

- Missing or superficial system risk assessments.

- Poor vendor and service provider oversight.

- Uncontrolled configuration changes and limited periodic review.

- Gaps in data integrity governance (e.g. uncontrolled local data storage, spreadsheets).

Practical consequence: For Annex 11 vs 21 CFR Part 11, inspection themes overlap but the angle differs: FDA often challenges the trustworthiness of records; EU authorities often challenge governance, lifecycle discipline, and risk management. A mature system must withstand both perspectives.

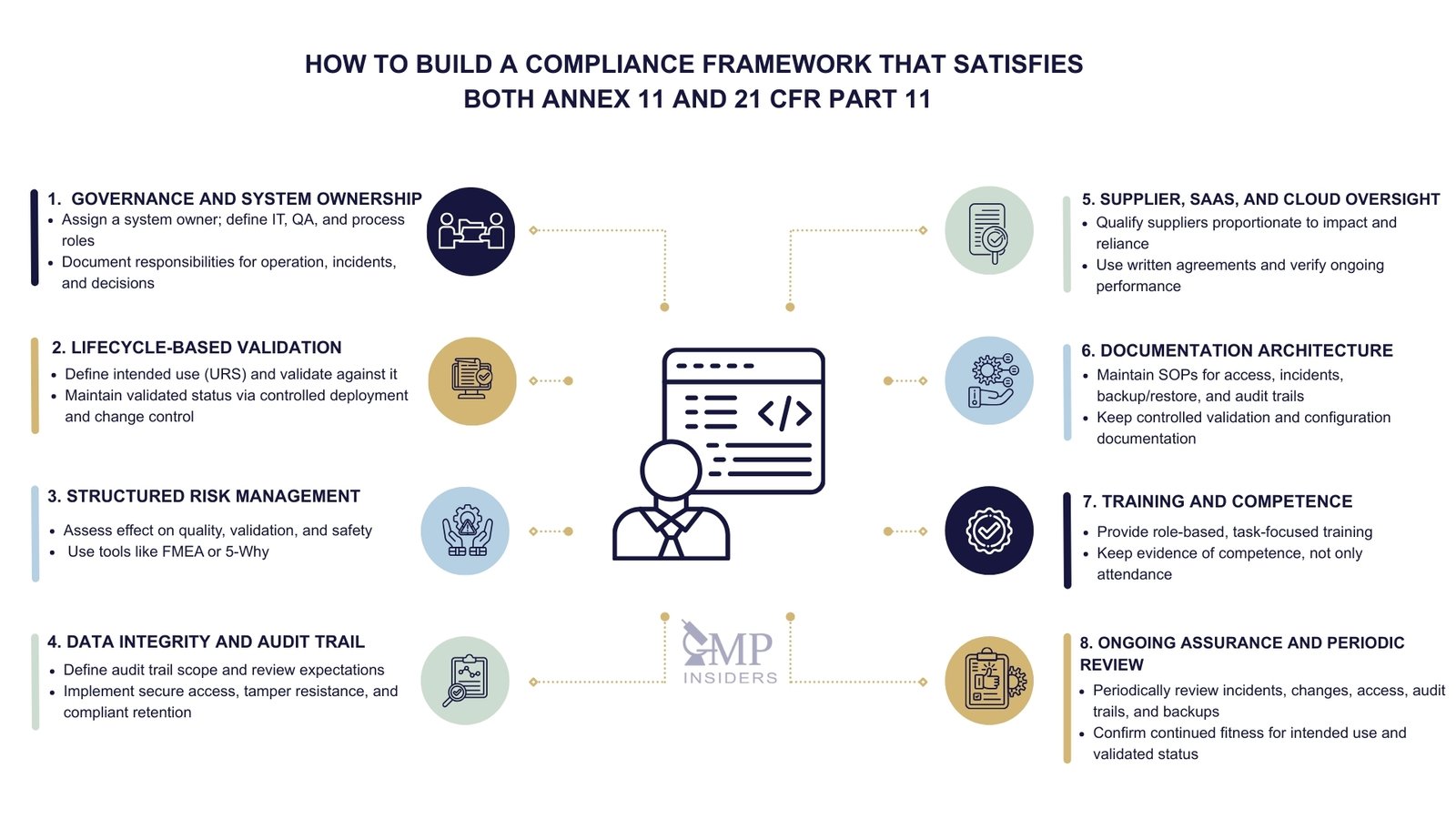

How to Build a Compliance Framework That Satisfies Both Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11

To operate confidently under both frameworks, organisations need a structured approach rather than isolated technical fixes. The following elements constitute a compliance framework that aligns with Annex 11 expectations and fully supports Part 11 requirements.

Clear Governance and System Ownership

Authorities expect clarity on who is responsible for what. Each computerized system should have:

- A defined system owner accountable for fitness, control, and compliance.

- Clear differentiation between process owner, IT responsibilities, and QA oversight.

- Documented allocation of roles covering use, maintenance, incident handling, and decision making.

Common weaknesses:

- Systems treated as “IT tools” without QA involvement.

- No clear ownership or fragmented accountability between departments.

Good practice:

- Governance model embedded in the pharmaceutical quality system.

- Responsibilities formally defined and auditable.

A Lifecycle-Based Validation Approach

Validation is not a single activity at go-live; it is a lifecycle discipline.

Authorities expect:

- Documented user requirements.

- Justified system design/configuration.

- Risk-based verification and validation.

- Controlled deployment and acceptance.

- Managed change control.

- Evidence that validation status remains current.

Common weaknesses:

- Retrospective “validation packages” assembled to satisfy audits.

- Testing focused only on functionality, not intended use or data integrity.

- No alignment between validation scope and system criticality.

Good practice:

- Lifecycle aligned with Annex 11, Annex 15, FDA expectations, and GAMP principles.

- Validation proportionate to risk, complexity, and data criticality.

Structured Risk Management

Authorities expect documented, defensible decision-making, not assumptions.

Risk management should:

- Classify systems based on impact.

- Justify validation depth.

- Justify the requirements for audit trails, redundancy, segregation of duties, and controls.

- Drive ongoing assurance activities.

Common weaknesses:

- No system risk assessments.

- Generic, template-based risk assessments without meaningful evaluation.

- “Risk” used as justification to avoid controls rather than define them.

Good practice:

- Risk management integrated with QMS processes.

- Decisions traceable, justified, and explainable to inspectors.

Data Integrity and Audit Trail Strategy

Authorities expect electronic records to be attributable, complete, consistent, secure, and reviewable.

This requires:

- Defined audit trail activation strategy.

- Defined scope of what requires audit trails.

- Procedures for routine audit trail review where appropriate.

- Protection against unauthorised access and manipulation.

- Retention aligned with record retention obligations.

Common weaknesses:

- Audit trails are enabled but never reviewed.

- Risk-based exclusion of audit trails without justification.

- Shared logins, weak credential controls, or uncontrolled local data storage.

Good practice:

- Risk-based but defensible implementation.

- Evidence that audit trail expectations are operational, not theoretical.

Supplier, SaaS, and Cloud Oversight Model

Outsourcing does not transfer regulatory responsibility.

Authorities expect:

- Supplier qualification proportionate to system impact.

- Assessment of vendor competence, quality system, and development approach.

- Written agreements defining responsibilities.

- Evidence that vendor documentation is critically assessed, not blindly accepted.

Common weaknesses:

- Declaring “vendor compliant to Part 11” as sufficient.

- No qualification records.

- Inadequate oversight of hosted systems.

Good practice:

- Supplier oversight embedded in the QMS.

- User validation supported by vendor documentation but not replaced by it.

Documentation Architecture

Compliance must be demonstrable.

Authorities expect:

- SOPs covering system use, access control, security, incident handling, backup/restore, audit trails, and data handling.

- Validation documentation.

- Training records.

- Controlled configuration documentation.

Common weaknesses:

- Partial documentation focused only on IT activity.

- Missing integration between system procedures and corporate QMS.

Good practice:

- Documentation consistent with the lifecycle and risk model.

- Clear, logical, and defendable.

Training and Competence

Systems are only trustworthy when operated competently.

Authorities expect:

- Role-based training.

- Records demonstrating competence.

- Reinforcement through routine oversight.

Common weaknesses:

- Generic training without relevance.

- No competence demonstration beyond attendance.

Good practice:

- Practical, task-focused training.

- Demonstrable understanding of responsibilities.

Ongoing Assurance and Periodic Review

Compliance must remain current.

Authorities expect:

- Periodic review of system performance, incident history, audit trail use, backup success, deviations, and changes.

- Confirmation that systems remain validated and fit for purpose.

Common weaknesses:

- No periodic review process.

- Validation treated as a one-time event.

Good practice:

- Periodic review embedded in governance.

- Evidence that continuous suitability is actively verified.

Risk-Based CSA Under 21 CFR Part 11

Computerised Software Assurance (CSA) is a risk-based assurance framework published by the U.S. FDA in 2025, intended to modernise how software used in medical device production and quality systems is assured, particularly with respect to 21 CFR Part 11 and broader quality system expectations. It replaces or supersedes prior validation guidance for quality systems software (e.g., Section 6 of “General Principles of Software Validation”).

Key characteristics of CSA:

- Focuses on risk-based assurance rather than exhaustive documentation.

- Scales assurance activities to the intended use of the software and its process risk, especially where quality, patient safety, or data integrity could be affected.

- Encourages combining different assurance methods (scripted testing, unscripted/exploratory testing, vendor evidence, monitoring) based on risk.

- Aims to maintain confidence in software without unnecessary burden where risk is low.

Practical implication: CSA does not replace Part 11; instead, it provides a contemporary interpretation of how assurance activities (including validation) should be conducted under Part 11 and quality system regulations (e.g., 21 CFR 820), particularly for computerized systems in medical device production/quality use.

SEE ALSO: CSV vs CSA: Key Differences in Software Validation

FAQ

Are Mobile Devices, Tablets, and Handheld Equipment in Scope for Annex 11 and Part 11?

Yes, if they are used to create, process, review, approve, or store GMP-relevant data, they fall within scope. Authorities expect the same level of control as for traditional desktop environments, including secure access, audit integrity, and verification of system reliability.

Mobile deployment must account for additional risk factors, such as device loss, shared use, and dependence on connectivity. Organisations must demonstrate that controls are defined, implemented, and maintained with documented justification.

Do Annex 11 and Part 11 Apply to Spreadsheets?

Yes, when spreadsheets are used to support GMP activities or maintain records relevant to compliance. Regulators consistently view spreadsheets as computerized systems requiring validation and control. Expectations typically include locked structures, version control, restricted access, defined ownership, and auditability, where risk warrants it. “It is only Excel” is not an acceptable defence; functionality does not exempt compliance.

How Do Annex 11 and Part 11 Treat AI-Based or Algorithmic Decision-Making Systems?

Such systems fall under the scope of computerized system expectations when they influence GMP decisions or records. Authorities expect transparency into how decisions are generated, assurance of algorithmic reliability, and documented justification for trust in the outputs.

Validation must address not only functionality but also data quality, training datasets, updates, and performance drift. Risk management becomes critical to demonstrating ongoing suitability.

How Should Organisations Manage System Configuration Versus Customisation?

Authorities expect clarity and justification for configuration choices and a strong rationale for any customisation. Custom solutions typically require deeper validation and supporting evidence. Organisations should maintain documented configuration baselines and change history. Failure to control configuration is frequently viewed as weak lifecycle governance.

How Should Organisations Handle System Retirement or Decommissioning?

Authorities expect structured decommissioning with preserved data integrity, retrievability, and ongoing access to retained records. Migration must be validated, and data checks performed. Risk assessment should determine the level of verification required. Uncontrolled system shutdowns remain a frequent weakness during inspections.

How Do Annex 11 and Part 11 Relate to ALCOA Principles?

Both frameworks inherently support ALCOA and ALCOA+ expectations, even if they are not explicitly referenced. Records must be attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate. Authorities interpret system-control decisions through a lens of data integrity. Failure to align with ALCOA expectations undermines the credibility of compliance.

Final Thoughts

Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 are not competing or interchangeable frameworks. One focuses on the lifecycle control of computerized systems within the pharmaceutical quality system; the other defines the conditions under which electronic records and electronic signatures can be accepted as reliable, reviewable evidence.

Authorities do not assess them in isolation. They seek a coherent model that demonstrates controlled systems, reliable records, and defensible decision-making.

Organisations that treat compliance as a checklist of technical features, such as enabled audit trails, configured signatures, or collected vendor certificates, continue to generate repeat findings. What differentiates mature practice is structured governance, documented risk management, lifecycle-based validation, and visible integration of computerized systems into the quality system.

The question is no longer “Are we Annex 11 or Part 11 compliant?” but “Can we demonstrate, with evidence, that our systems and records can be relied on in every critical step they support?”

The ongoing evolution of expectations, reflected in the Draft Annex 11 revision and in CSA, confirms the direction of travel: risk-based assurance, lifecycle control, and data integrity as a continuous discipline rather than a one-time validation exercise. Organisations that adopt this mindset will not only align with Annex 11 and Part 11 today, but will also be better positioned for the next wave of guidance and inspections.