Moist heat sterilization is the most established and widely accepted sterilization method in the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industries. Where product formulation, materials, and container systems allow, it remains the preferred approach due to its proven effectiveness, reproducibility, and strong regulatory acceptance. Despite this long history, moist heat sterilization is still frequently misunderstood and oversimplified in GMP environments.

In many organizations, moist heat sterilization is treated as synonymous with “autoclaving” and reduced to the routine use of a default cycle, typically 121 °C for 15 minutes. This simplified view ignores that moist heat sterilization is not a single technology but a family of processes, each governed by distinct physical mechanisms, limitations, and risks. When these differences are not understood, inappropriate cycle selection, weak validation strategies, and avoidable GMP observations often follow.

This article explains what moist heat sterilization is, how it works, and where it is applied in pharmaceutical manufacturing. It focuses on the fundamental principles, process types, and regulatory context needed to understand the technology without delving into cycle-selection logic or detailed validation strategies.

Definition and Scope of Moist Heat Sterilization

Moist heat sterilization is a process that inactivates microorganisms by applying heat in the presence of moisture, typically delivered as saturated steam or, in certain applications, as hot water under controlled pressure.

In pharmaceutical GMP terms, the defining feature is not the heat source itself, but the presence of water in liquid or vapor form, which enables efficient heat transfer and rapid microbial inactivation.

Within pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturing, moist heat sterilization is applied to a wide range of items, including:

- Terminal sterilization of aqueous medicinal products

- Sterilization of product-contact components and equipment

- Processing of hard goods, porous materials, and selected container systems

Importantly, moist heat sterilization is not limited to traditional saturated steam autoclaves. Modern GMP frameworks explicitly recognize alternative moist-heat systems, such as steam–air mixture processes and superheated hot-water systems, when required to protect container integrity or accommodate specific product and packaging constraints.

The scope of moist heat sterilization does not extend to all sterilization technologies. Processes such as dry heat depyrogenation, ethylene oxide sterilization, and radiation-based methods rely on fundamentally different mechanisms and are governed by separate regulatory and validation frameworks. These methods are therefore considered outside the scope of moist heat sterilization and are addressed independently within GMP systems.

SEE ALSO: Terminal Sterilization vs Aseptic Processing: Key Differences

This clear definition and scope are essential, as regulatory expectations, validation approaches, and routine control strategies for moist heat sterilization are intrinsically linked to the underlying mechanism by which moisture and heat act together to achieve sterility.

| Process / Technology | Moisture Present | Primary Mechanism | Typical GMP Use | In Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated steam (autoclave) | Yes (steam) | Condensation & latent heat | Equipment, components, hard goods | Yes |

| Pre-vacuum steam | Yes (steam) | Steam penetration after air removal | Porous and hollow loads | Yes |

| Steam–air mixture (SAM) | Yes (steam + air) | Controlled heat + pressure | Sealed containers, PFS, BFS | Yes |

| Superheated hot-water systems | Yes (liquid water) | Direct water heat transfer | LVPs, sealed aqueous products | Yes |

| Dry heat depyrogenation | No | Oxidative / high-temperature heat | Glass depyrogenation | No |

| Ethylene oxide (EtO) | No | Chemical alkylation | Heat-sensitive devices | No |

| Radiation (gamma, e-beam) | No | Ionizing radiation | Medical devices, APIs | No |

How Moist Heat Sterilization Works

Moist heat sterilization relies on the presence of water, either as saturated steam or as hot liquid water, to efficiently transfer thermal energy to microorganisms. Water has significantly higher heat-transfer capacity than dry air; therefore, moist heat achieves microbial inactivation at lower temperatures and shorter exposure times than dry heat.

In steam-based systems, the critical event is condensation. When saturated steam contacts a cooler surface, it condenses into water, releasing latent heat. This rapid energy release causes an immediate, uniform increase in surface temperature, which is essential for effective microbial kill. In the absence of moisture, this mechanism does not occur, severely compromising sterilization effectiveness.

Steam Condensation and Latent Heat Transfer

Latent heat released during steam condensation is the dominant driver of lethality in moist heat sterilization. Unlike sensible heat (the temperature increase measured in air), latent heat releases a large amount of energy at constant temperature, making it highly efficient.

For this reason:

- Steam must physically contact the load surface

- Residual air must be minimized or eliminated

- Condensate must be allowed to drain to maintain continuous heat transfer

Any condition that prevents condensation, such as trapped air, superheated steam, or inadequate circulation, reduces sterilization effectiveness, even if the chamber temperature appears correct.

Microbial Inactivation Mechanism

Moist heat inactivates microorganisms primarily by irreversibly denaturing proteins and enzymes essential to cellular metabolism and replication. This mechanism affects vegetative bacteria, fungi, and spores, with bacterial spores typically representing the most resistant challenge for moist heat processes.

The rate of inactivation depends on:

- Temperature at the microbial location

- Duration of exposure

- Moisture availability at the contact surface

Because this mechanism is well understood and reproducible, moist heat sterilization is considered a robust and predictable process when physical conditions are controlled.

Sterility Assurance and Quantitative Lethality Concepts

Sterility assurance in pharmaceutical manufacturing is expressed probabilistically through the Sterility Assurance Level (SAL). For terminally sterilized medicinal products, an SAL of 10⁻⁶ is typically expected, corresponding to a 1-in-1,000,000 probability of a non-sterile unit.

To quantify lethality, several interrelated parameters are used:

- D-value, which quantifies microbial resistance at a specific temperature

- z-value, which describes how microbial resistance changes with temperature

- F₀, which integrates time and temperature into a single cumulative lethality metric referenced to 121 °C

| Parameter | What It Describes | What It Assumes | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-value | Microbial resistance at a given temperature | Uniform exposure conditions | Does not confirm steam contact |

| z-value | Temperature sensitivity of microbial death | Predictable thermal response | Independent of physical load effects |

| F0 | Cumulative lethality referenced to 121 °C | Representative product temperature | Can mask air removal or penetration failures |

| SAL | Probability of non-sterile unit | Validated, controlled process | Not measured directly per cycle |

These parameters are mathematical tools that describe microbial kill under defined conditions. They do not, by themselves, confirm that the required physical conditions, such as steam contact or uniform heating, were achieved throughout the load.

Physical Limitations That Affect Lethality

In practice, the effectiveness of moist heat sterilization is often limited by physical rather than microbiological factors. Common limitations include:

- Incomplete air removal, which blocks steam contact

- Non-uniform heat distribution within the chamber or load

- Load shielding and cold spot formation

- Inadequate condensate removal

- Packaging or container features that impede heat transfer

These factors explain why identical time–temperature profiles can produce different outcomes depending on load configuration and process design. They also explain why calculated lethality must always be interpreted in the context of physical process performance.

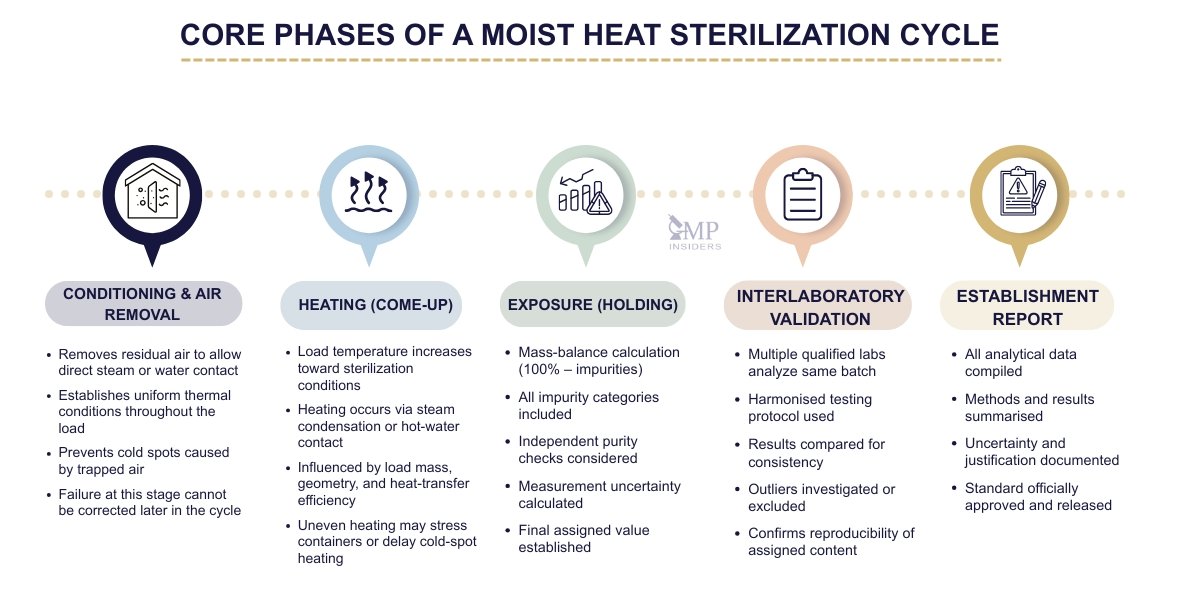

Core Phases of a Moist Heat Sterilization Cycle

Although moist heat sterilization processes may differ in design and application, all steam- and water-based cycles follow a defined sequence of phases. Each phase has a specific function and directly influences sterility assurance, product quality, and container integrity.

Understanding these phases is essential for interpreting cycle performance and identifying potential risks.

1. Conditioning and Air Removal Phase

The conditioning phase prepares the load for effective sterilization by removing air and establishing the correct thermal environment. In steam-based systems, this is achieved through gravity displacement, active vacuum pulses, or a combination of both.

Air is the primary antagonist of moist heat sterilization. If air remains trapped within the chamber or load, steam cannot contact critical surfaces, condensation does not occur, and heat transfer does not occur. This results in cold spots that may not reach sterilizing conditions, even when the chamber temperature appears acceptable.

The effectiveness of this phase depends on:

- The air removal method employed

- Load geometry and porosity

- Packaging materials and drainage characteristics

Failure in the conditioning phase compromises the entire sterilization process and cannot be compensated for by simply extending exposure time.

2. Heating (Come-Up) Phase

During the heating phase, the load temperature increases toward the target sterilization temperature. This phase is influenced by the load’s thermal mass, the rate of steam or water delivery, and the heat-transfer efficiency.

In steam cycles, heating occurs as steam condenses on cooler surfaces. In hot-water systems, heating occurs through direct contact with circulating water. The heating profile is particularly important for liquid loads and sealed containers, where internal temperatures may lag significantly behind chamber conditions.

Uneven or excessively rapid heating can introduce risks, including:

- Delayed heating at cold spots

- Pressure differentials affecting container integrity

- Localized overheating or boiling in liquid products

3. Exposure (Holding) Phase

The exposure phase is the period during which sterilizing conditions are intentionally maintained to deliver the required microbial lethality. Traditionally, this phase is defined by a specified temperature and time, but its effectiveness depends on conditions established in earlier phases.

For exposure to be meaningful:

- All critical locations must already be at sterilizing temperature

- Steam or water contact must be maintained

- Pressure conditions must remain within validated limits

The exposure phase does not correct deficiencies in air removal or heat transfer. Its role is to maintain lethality once the proper physical conditions are met.

4. Exhaust, Depressurization, and Drying Phase

Following exposure, the sterilization medium is removed, and the system transitions toward ambient conditions. In steam cycles, this involves exhaust and, where applicable, vacuum drying. In water-based systems, controlled drainage and pressure reduction are used.

This phase is critical for:

- Preventing excessive condensate retention

- Avoiding recontamination or moisture-related quality issues

- Protecting container closure systems from stress

Poorly controlled exhaust or drying can result in wet loads, container deformation, or compromised package integrity, all of which have GMP implications.

5. Cooling and Pressure Control Phase

Cooling brings the load to a safe handling temperature and stabilizes the system. For sealed liquid products, cooling must be carefully controlled to prevent internal overpressure or vacuum formation, which could damage containers or compromise closure integrity.

In processes such as steam–air mixture or superheated hot-water systems, pressure is actively controlled during cooling to balance internal and external forces acting on the container. Inadequate control during this phase can render an otherwise successful sterilization process ineffective.

Types of Moist Heat Sterilization Processes Used in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Moist heat sterilization is not a single, uniform process. It encompasses a range of technologies that differ in how heat and moisture are delivered, how pressure is controlled, and which physical risks dominate. Regulatory frameworks explicitly recognize these differences, and GMP compliance depends on applying each process within its intended scope of use.

Gravity Displacement Steam Sterilization

Gravity displacement cycles rely on the natural tendency of steam to displace air downward and out of the chamber. Because air removal is passive, these cycles have limited capability to eliminate residual air from complex or porous loads.

Typical applications include:

- Unwrapped metal instruments

- Simple glassware

- Loads with minimal internal voids or shielding

The primary limitation of gravity displacement cycles is air entrapment, which can prevent steam from contacting all load surfaces. As a result, these cycles are limited to simple, non-porous items and are unsuitable for wrapped, porous, or hollow loads.

Pre-Vacuum (Porous Load) Steam Sterilization

Pre-vacuum cycles actively remove air using one or more vacuum pulses prior to steam exposure. This design enables effective steam penetration into porous materials and complex geometries.

Typical applications include:

- Textiles and gowning

- Filters and stopper bags

- Tubing, hoses, and hollow or layered components

These cycles are specifically engineered to address air removal and steam penetration challenges. They represent the standard approach for porous and hollow loads in GMP environments. Their effectiveness depends on robust vacuum performance, proper load configuration, and reliable steam quality.

Saturated Steam Liquid Sterilization Cycles

Liquid cycles are used for aqueous products sterilized in open or vented containers. In these processes, sterilization effectiveness is governed by heat transfer into the liquid, rather than by steam penetration into a porous structure.

Typical applications include:

- Aqueous products in open or loosely vented containers

- Liquids requiring controlled exhaust to prevent boil-over

Because the liquid itself heats more slowly than the chamber environment, internal product temperature is the critical determinant of lethality. Chamber temperature alone does not represent sterilization conditions for these loads.

Steam–Air Mixture (SAM) Processes

Steam–air mixture processes combine steam with controlled amounts of air, allowing independent control of temperature and pressure. This makes them suitable for sealed containers that would otherwise be damaged by pressure differentials in saturated steam cycles.

Typical applications include:

- Pre-filled syringes

- Blow-Fill-Seal (BFS) and Form-Fill-Seal (FFS) containers

- Flexible or semi-rigid sealed containers

In SAM processes, both heat transfer and container integrity are critical. Pressure is deliberately managed during heating and cooling to protect the container while still achieving sterilizing conditions.

Superheated Hot-Water Shower / Cascade Processes

Superheated hot-water systems deliver heat through direct contact with circulating water under controlled pressure. Unlike steam cycles, wet loads are acceptable because the products are terminally sealed before sterilization.

Typical applications include:

- Sealed aqueous products in rigid containers

- Large-volume parenterals (LVPs)

- Ampoules and similar formats

These systems offer highly uniform heat transfer and excellent pressure control, making them well-suited for heat-sensitive formulations or containers requiring counter-pressure protection. Effective drainage, water distribution, and temperature uniformity are essential to their performance.

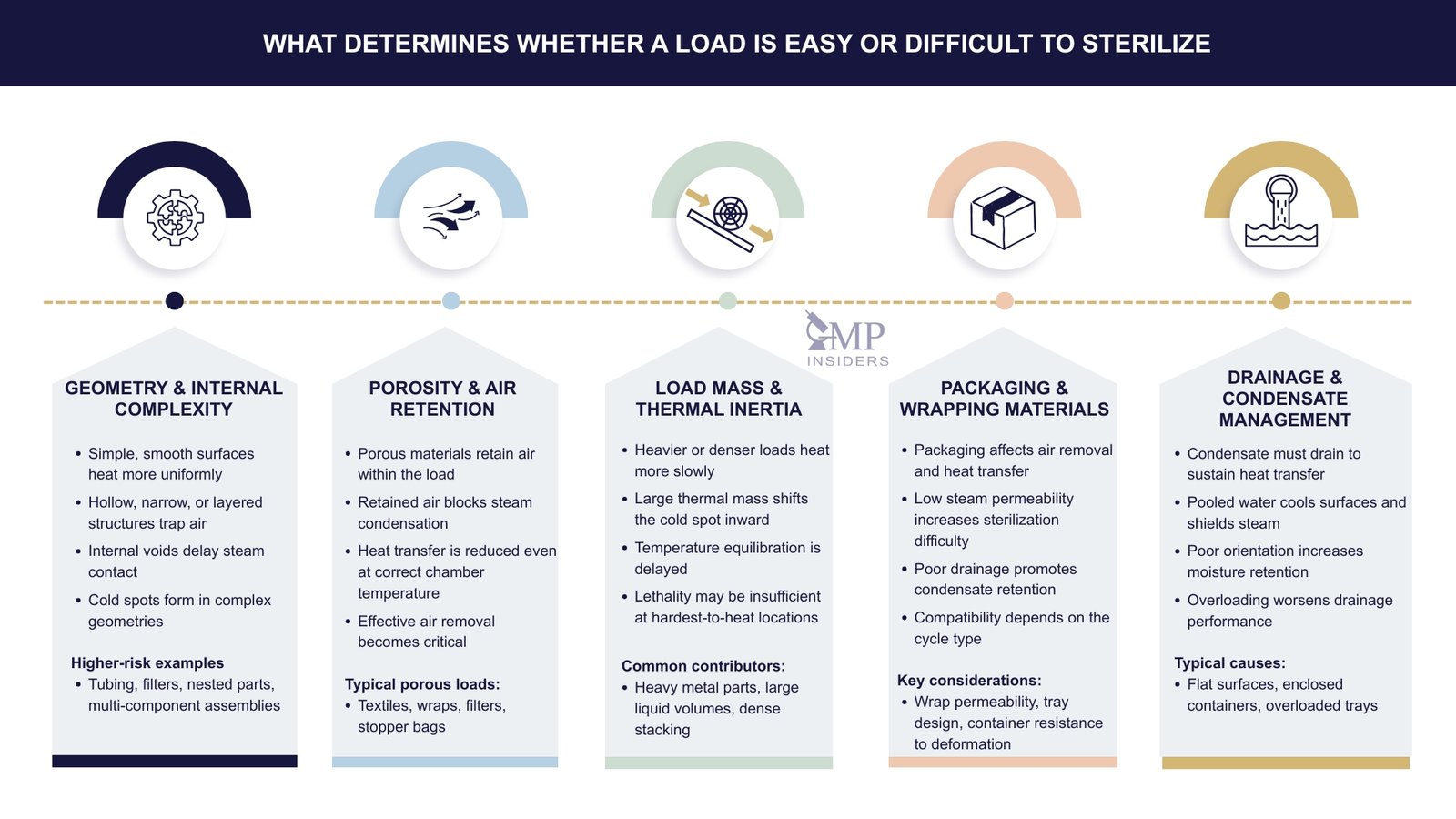

What Determines Whether a Load Is Easy or Difficult to Sterilize

Not all items respond to moist heat sterilization in the same way. Even when the same sterilizer and nominal cycle parameters are used, the physical characteristics of the load can dramatically influence sterilization effectiveness. From a GMP perspective, this is one of the most frequently underestimated aspects of moist heat sterilization.

The difficulty of sterilizing a load is primarily driven by how readily moist heat can reach, transfer energy to, and uniformly condition all critical locations within it.

Geometry and Internal Complexity

Simple, solid items with smooth external surfaces are generally easier to sterilize than loads with complex internal features. Hollow components, narrow lumens, bends, dead legs, and layered assemblies can trap air and restrict contact between steam or water.

Examples of higher-risk geometries include:

- Long or narrow tubing

- Filters and stopper bags

- Nested or stacked components

- Multi-part assemblies with internal voids

As internal complexity increases, the risk that certain locations will experience delayed heating or incomplete exposure to moist heat increases.

Porosity and Air Retention

Porous materials, such as textiles, filters, or wrapped components, can retain significant volumes of air. This retained air must be effectively removed during the conditioning phase to allow steam penetration.

If air removal is incomplete:

- Steam cannot condense uniformly

- Heat transfer is impaired

- Cold spots may persist despite acceptable chamber conditions

Porosity, therefore, represents a fundamental challenge for moist heat processes and requires appropriate cycle design and load configuration.

Load Mass and Thermal Inertia

Large or densely packed loads absorb heat more slowly than light or loosely arranged loads. High thermal mass can delay temperature equilibration and shift the cold spot deeper into the load.

Factors that increase thermal inertia include:

- Heavy metal components

- High fill volumes of liquid products

- Dense stacking or close packing

If not properly accounted for, thermal inertia can result in insufficient lethality at the most difficult-to-heat locations.

Packaging and Wrapping Materials

Packaging materials influence both air removal and heat transfer. Wraps, pouches, trays, and containers can act as barriers if they are not compatible with the selected sterilization process.

Key considerations include:

- Steam permeability of wraps

- Drainage capability of trays and containers

- Resistance of packaging to deformation or collapse

Packaging that performs well in one cycle type may behave poorly in another, reinforcing the need for process-specific justification.

Drainage and Condensate Management

Effective drainage is essential for maintaining continuous heat transfer during steam sterilization. Accumulated condensate can shield surfaces, cool local areas, and interfere with sterilization.

Poor drainage may result from:

- Flat or enclosed surfaces

- Improper load orientation

- Overloaded trays or baskets

Loads that do not drain effectively are inherently more difficult to sterilize and require careful consideration during process design.

Common Misunderstandings and Oversimplifications in Moist Heat Sterilization

Despite its long-standing use in pharmaceutical manufacturing, moist heat sterilization is still frequently applied in an oversimplified manner. Many of the recurring deficiencies observed during inspections are not due to a lack of equipment or standards, but to misinterpretation of how the process actually works.

“121 °C for 15 Minutes” as a Universal Rule

One of the most persistent misconceptions is that a single time, temperature combination can be applied universally to all loads. While 121 °C for 15 minutes is a historically established reference condition, it does not guarantee effective sterilization in every application.

This approach ignores:

- Differences in load geometry and packaging

- Air removal and steam penetration challenges

- Heat transfer limitations in liquid or dense loads

Regulators increasingly challenge this practice when it is applied without a clear, load-specific scientific rationale.

Equating Chamber Temperature with Sterilization Conditions

Another common error is assuming that chamber temperature represents the temperature experienced by the load or product. In reality, the coldest point of the load, often located deep within a product or in a shielded area, determines sterilization effectiveness.

For many applications, particularly liquid products and sealed containers, chamber temperature provides only indirect information and cannot be used as a surrogate for product temperature without justification.

Treating All Steam Cycles as Equivalent

Steam sterilization is often treated as a single category, with gravity, pre-vacuum, liquid, and alternative moist-heat cycles grouped under the term “autoclaving.” This obscures the fact that these processes are governed by different physical mechanisms and are intended for different types of loads.

Applying validation and routine control logic from one cycle type to another is a frequent source of GMP findings.

Over-Reliance on Calculated Lethality

Calculated lethality metrics, such as F₀, are powerful tools when applied correctly. However, they are sometimes used as universal acceptance criteria without regard to whether the product temperature accurately reflects the sterilizing conditions.

Where air removal or steam penetration is the dominant risk, calculated lethality alone may mask underlying physical failures, giving a false sense of security.

Assuming Validation Can Compensate for Poor Process Design

Validation cannot correct a fundamentally inappropriate sterilization process. Extending exposure time, increasing temperature, or adding additional indicators cannot compensate for poor air removal, inadequate drainage, or unsuitable load configuration.

Regulatory expectations emphasize that process design must be appropriate before validation is performed, not adjusted afterward to justify an unsuitable approach.

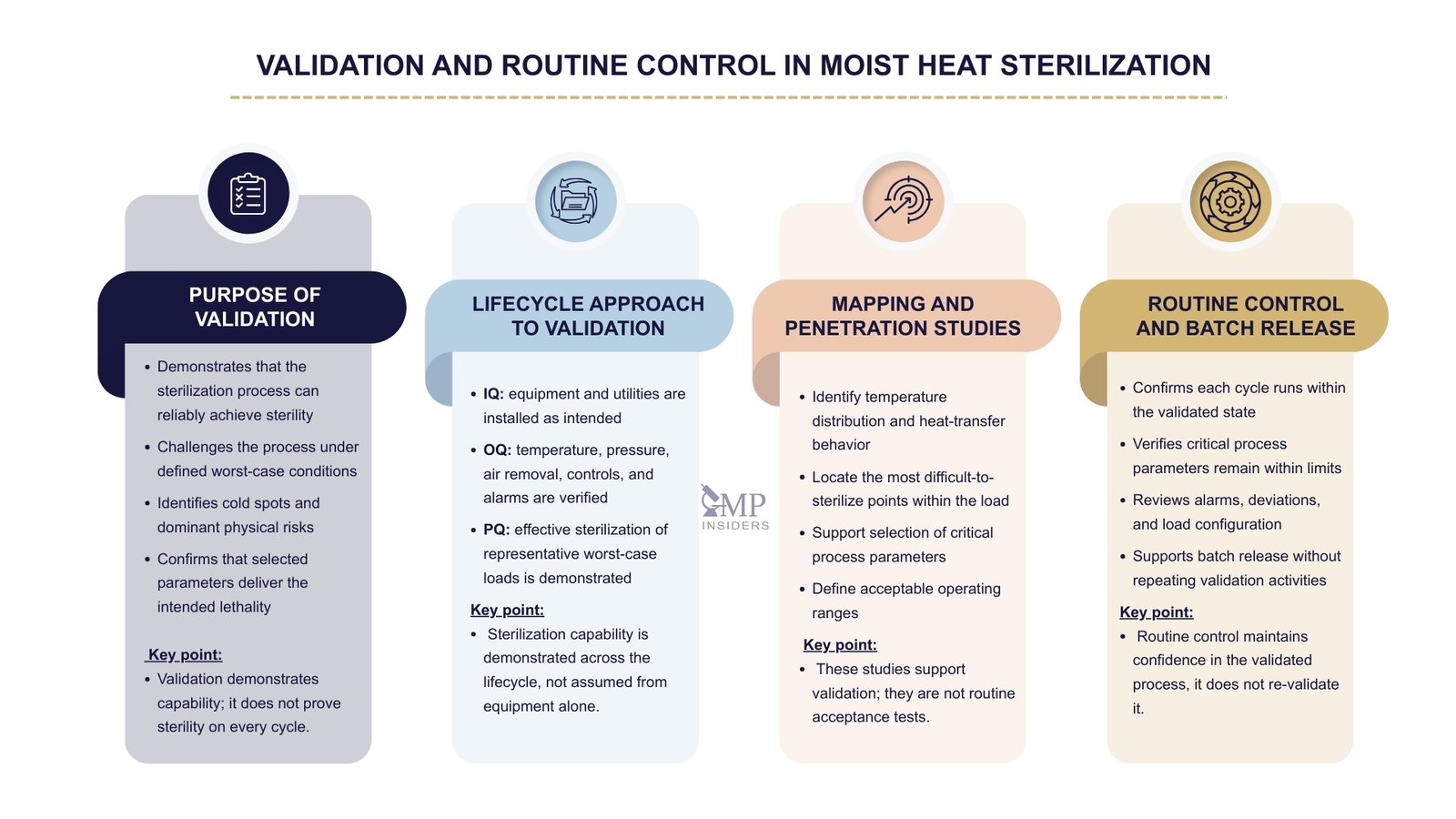

Validation and Routine Control: A High-Level Overview

Validation and routine control are often discussed together, but they serve distinct and complementary purposes within a moist heat sterilization program. Confusing these roles is a common source of weak justifications and regulatory findings. At a high level, validation demonstrates that a sterilization process is capable, while routine control confirms that the validated state is maintained during daily operation.

Purpose of Validation in Moist Heat Sterilization

Validation establishes documented evidence that a moist heat sterilization process can reliably achieve the required level of sterility under defined worst-case conditions. It is not intended to repeatedly prove sterility, but to demonstrate that the process design, parameters, and controls are fundamentally sound.

In practical terms, validation addresses:

- Whether the selected sterilization process can control the dominant physical risks

- Where the coldest or most difficult-to-sterilize locations are

- Whether process parameters consistently achieve the intended lethality

Validation is therefore a one-time (or infrequent) demonstration of capability, performed under carefully designed and challenged conditions.

Lifecycle Approach to Validation

Modern GMP expectations frame sterilization validation as a lifecycle activity rather than a single event. This includes:

- Installation Qualification (IQ): confirming the sterilizer and utilities are installed correctly

- Operational Qualification (OQ): verifying control of temperature, pressure, air removal, alarms, and safety systems

- Performance Qualification (PQ): demonstrating effective sterilization of representative worst-case loads

This lifecycle approach ensures that sterilization capability is not assumed based solely on equipment, but is demonstrated in the context of real loads and operating conditions.

SEE ALSO: IQ, OQ and PQ in GMP

Role of Mapping and Penetration Studies

Mapping and penetration studies are tools used during validation to understand process behavior. Their purpose is to identify the temperature distribution, heat-transfer characteristics, and locations where sterilization is most difficult to achieve.

These studies do not define routine acceptance criteria. Instead, they provide the scientific basis for:

- Selecting critical process parameters

- Defining acceptable operating ranges

- Establishing routine monitoring points

Once validation is complete, these studies are not repeated on a batch-by-batch basis.

Routine Control and Batch Release

Routine control confirms that each sterilization cycle is executed within the validated state. It focuses on verifying that critical process parameters remain within predefined limits and that no events occurred that could compromise sterility assurance.

Routine batch release typically involves:

- Review of critical cycle parameters

- Confirmation of alarms and deviations

- Verification of adherence to validated load configuration

Importantly, routine release does not repeat validation activities or re-establish worst-case conditions.

Key Regulatory Guidelines Governing Moist Heat Sterilization

Moist heat sterilization in the pharmaceutical industry is governed by a network of harmonised regulatory guidelines and international standards. These documents do not prescribe fixed cycle parameters; rather, they collectively establish expectations for process selection, validation, control, and documentation, grounded in scientific understanding and risk management.

Below is a concise, GMP-oriented overview of the most relevant guidelines, intended to support practical interpretation rather than to restate regulatory text.

EU GMP Annex 1 (2022): Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products

EU GMP Annex 1 is the most influential regulatory document shaping current expectations for moist heat sterilization in Europe and globally.

Key principles relevant to moist heat sterilization include:

- Moist heat sterilization is not limited to saturated steam; alternative systems such as steam–air mixtures and superheated hot-water systems are explicitly permitted when justified.

- Sterilization processes must be appropriate for the load and container system, rather than selected by default

- Effective air removal and steam penetration must be assured and routinely verified for porous and hard-goods loads.

- For fluid sterilization, temperature, time, and/or F₀ may be used as acceptance criteria, recognizing heat transfer as the governing mechanism.

- Heat-sensitive or non-rigid containers must be protected through pressure control and controlled heating/cooling rates.

- Alternative moist-heat systems require enhanced validation, including full-load temperature mapping and demonstration of uniformity and reproducibility.

Annex 1 clearly positions moist heat sterilization as a risk-based, mechanism-dependent process and embeds it within the Contamination Control Strategy (CCS).

See Also: Risk-based Decision Tree for Heat Moist Sterilization

EMA Guideline on the Sterilisation of the Medicinal Product, Active Substance, Excipient and Primary Container

This EMA guideline complements Annex 1 by providing more detailed expectations for terminal sterilization and post-aseptic heat treatment.

Key regulatory clarifications include:

- Differentiation between:

- Reference and overkill terminal steam sterilization cycles

- Reduced lethality cycles (F₀ ≥ 8 minutes), which require increased validation effort

- Post-aseptic terminal heat treatment (F₀ < 8 minutes), which is not equivalent to terminal sterilization

- Explicit linkage between bioburden assumptions, delivered lethality, and validation depth

- Clear expectations for dossier justification when non-standard sterilization approaches are applied

This guideline underscores that not all steam-based processes provide equivalent sterility assurance and that validation and control strategies must reflect the chosen approach.

ISO 17665: Sterilization of Health Care Products — Moist Heat

ISO 17665 provides the international standard framework for the development, validation, and routine control of moist heat sterilization processes.

Key ISO principles include:

- Sterilization processes must be selected based on product and load characteristics, not equipment capability alone.

- Validation and routine control must reflect the actual sterilization mechanism (air removal, steam penetration, heat transfer).

- Lethality metrics such as F₀ should be applied only where meaningful measurements of product temperature are possible.

- A lifecycle approach is required that covers development, qualification, routine control, and requalification.

ISO 17665 strongly supports the risk-based, load-specific expectations articulated in Annex 1.

PDA Technical Reports (Supporting Industry Guidance)

While not regulatory documents, PDA Technical Reports are frequently referenced during inspections as state-of-the-art industry guidance.

Relevant PDA documents include:

- PDA TR-1: Validation of Moist Heat Sterilization Processes

- PDA TR-48: Moist Heat Sterilization of Aqueous Liquids

These reports provide practical interpretations of regulatory and ISO requirements, particularly for air removal testing, load configuration, the use of biological indicators, and temperature mapping strategies.

FAQ

Why Is Condensate Considered a Risk Rather Than a Benefit?

Condensation is essential for heat transfer, but excess or retained condensate becomes a risk. Standing water can cool local surfaces, shield portions of the load, or impede steam contact.

It may also create downstream GMP issues such as wet loads, corrosion, or compromised packaging. Effective drainage and load design are therefore as important as achieving condensation itself. Regulators expect condensate behavior to be understood and controlled.

Can Extending Exposure Time Compensate for Poor Sterilization Performance?

Extending exposure time cannot reliably compensate for poor air removal, inadequate steam penetration, or ineffective heat transfer. If steam does not reach a surface, no amount of additional time will deliver lethal heat.

Regulators view time extensions that do not address root causes as weak and often unacceptable justifications. Exposure time should be increased only when the physical mechanism has been demonstrated to be effective. Otherwise, the process design itself must be corrected.

What Is the Regulatory Concern With “Over-Sterilization”?

Over-sterilization is not automatically acceptable simply because sterility is achieved. Excessive temperature or exposure can degrade products, damage containers, and create unnecessary stress on materials.

Regulators expect manufacturers to balance sterility assurance with product quality and container integrity. Applying unnecessarily harsh cycles without justification may indicate a lack of process understanding. Risk-based sterilization aims to achieve sufficient, not excessive, lethality.

Why Is Reproducibility More Important Than Peak Performance?

A sterilization process must be performed consistently, not merely occasionally achieve sterilizing conditions. Regulators focus on whether each cycle behaves predictably within validated limits.

A process that sometimes achieves higher lethality but varies widely is less acceptable than one that is stable and controlled. Reproducibility supports reliable batch release and meaningful assessment of deviations. It is a cornerstone of GMP compliance.

How Should Sterilization Failures Be Investigated Differently From Other Deviations?

Sterilization failures often involve complex physical phenomena rather than simple operator error. Investigations should therefore focus on air removal, heat transfer, load configuration, and equipment performance.

Superficial root causes such as “cycle aborted” are rarely sufficient. Regulators expect technically sound investigations supported by data and engineering input. Poor sterilization investigations are frequently escalated during inspections.

How Do Utilities Indirectly Affect Moist Heat Sterilization?

Utilities such as steam, compressed air, water, and electricity directly influence sterilizer performance. Variations in steam pressure, dryness, or supply stability can alter cycle behavior. Regulators expect utility qualification and monitoring to support sterilization claims.

Changes to utilities should trigger impact assessments. Sterilization cannot be isolated from its supporting systems.

Final Thoughts

Moist heat sterilization remains one of the most powerful and reliable sterilization methods available to the pharmaceutical industry, but only when it is applied with scientific understanding, process awareness, and risk-based control.

Its long history and broad regulatory acceptance should not be mistaken for simplicity. In reality, moist heat sterilization encompasses multiple technologies, each governed by different physical mechanisms, limitations, and risks.

Regulatory expectations have clearly evolved. Authorities no longer assess sterilization solely by whether a cycle reached a predefined temperature for a set time. They evaluate whether manufacturers understand how and why sterility is achieved for a given load, container system, and process design, and whether this understanding is consistently reflected in validation, routine control, and documentation.