Complaint management is a core element of the Pharmaceutical Quality System (PQS) and a direct indicator of how effectively an organisation controls its processes, understands its products, and protects patients.

Regulatory authorities consistently regard complaint handling as evidence of quality system maturity because it demonstrates whether a manufacturer can identify quality signals, assess risks objectively, investigate in technical depth, and implement sustainable corrective and preventive actions.

A complaint is a post-market quality signal that must be evaluated within a structured, documented, and scientifically justified framework. Complaint information must be linked to deviations, nonconformances, CAPAs, change control, product quality reviews, recall systems, and pharmacovigilance or vigilance processes, where applicable. The expectation is not simply to respond, but to demonstrate control, traceability, and evidence-based, risk-informed decision-making.

This article provides a structured, practice-oriented interpretation of complaint handling aligned with GMP expectations. It addresses foundational definitions and classifications; risk-based complaint triage; investigation principles; documentation quality; regulatory focus areas; governance; integration with the quality management system; and trend and metric analysis.

Definitions and Scope of Complaints

For an effective complaint management system, terminology must be precise, unambiguous, and consistently applied across the organisation. Misinterpretation of what constitutes a complaint is one of the most common weaknesses observed in practice and a frequent root cause of delayed assessment, poor trending, and missed quality signals.

A complaint is any written, verbal, electronic, or otherwise communicated allegation that a medicinal product, batch, or associated quality element may not meet the required quality, safety, identity, strength, purity, performance, packaging, labelling, usability, integrity, or expected functionality.

It may originate from healthcare professionals, distributors, pharmacies, internal personnel, regulatory agencies, patients, or other stakeholders. The format, tone, or completeness of the information provided does not change its status as a complaint.

A distinction must be made between quality-related complaints, medical/safety complaints, and non-quality communications:

- Quality complaints relate to product quality attributes, visual appearance, contamination, particulate matter, degradation, incorrect strength, breakage, leakage, packaging defects, labelling errors, product mix-ups, stability concerns, temperature excursion impact, sterility assurance concerns, or any indicator that the product may not comply with its approved specifications or quality standards.

- Performance or efficacy-related complaints concern perceived lack of effect or reduced performance. These require careful assessment and, where applicable, structured linkage to pharmacovigilance or vigilance activities.

- Safety-related complaints refer to adverse reactions or events. These are not handled solely as complaints; they require well-defined interfaces between complaint handling and pharmacovigilance or vigilance systems to ensure accurate data capture, triage, reporting, and follow-up.

- Distribution-related complaints may arise from storage, handling, transport, temperature excursions, damaged shipments, or suspected GDP failures. These may still represent quality risk and must not be dismissed solely as logistics issues.

- Non-quality communications such as general enquiries, product information requests, ordering issues, price concerns, or commercial matters are not complaints. However, systems must prevent inappropriate exclusion of legitimate quality concerns under the justification of “customer service” or “information only”.

| Communication / Report Type | What It Typically Includes (Examples) | Classified as Complaint? | Primary Handling Owner | Mandatory Interface / Escalation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality-related complaint | Visual defects, particulate matter, contamination indicators, degradation, incorrect strength, leakage, breakage, packaging defects, labelling errors, product mix-ups, stability concerns, temperature excursion impact, sterility assurance concerns | Yes | QA / Quality Unit | Investigation; possible deviation/nonconformance; CAPA; risk assessment; potential recall decision |

| Performance / efficacy-related complaint | Perceived lack of effect, reduced performance, “doesn’t work as expected” | Yes | QA (triage) + Medical as applicable | Link to PV/vigilance where required; assess for quality linkage (e.g., degradation, dosing, device function) |

| Safety-related complaint | Adverse reactions/events, safety signals reported by HCPs/patients | Yes (record remains) | PV / Vigilance (lead) + QA | Mandatory PV/vigilance triage, reporting, follow-up; QA maintains complaint record and quality impact assessment |

| Distribution / GDP-related complaint | Temperature excursions, damaged shipments, storage/handling concerns, suspected transport failures | Yes (if quality risk) | GDP/SCM + QA | Quality risk assessment; investigation; decision on disposition; potential escalation if product integrity impacted |

| Suspected counterfeit / tampering / falsified / integrity breach | Suspicious packaging, missing security features, signs of tampering, unusual supply path | Yes (elevated risk) | QA (lead) + Security/RA as applicable | Immediate escalation pathway; containment; notification considerations per local requirements; enhanced documentation |

| Non-quality communication | Product info requests, ordering/availability, pricing, commercial topics | No (unless quality allegation present) | Customer service / Commercial | Screening step required to prevent misclassification; reclassify to complaint if any quality/safety/performance allegation appears |

Additionally, complaint systems must recognise reports of suspected counterfeit or tampered products, suspected falsified products, and suspected product-integrity breaches as complaints with elevated risk relevance and structured escalation pathways.

SEE ALSO: Contamination, Cross-Contamination, and Mix-Ups in GMP

Finally, it is essential to differentiate between:

- a complaint (external signal),

- a deviation or non-conformance (internal event),

- and a return or recall action (consequence of risk decision).

A complaint may trigger internal investigations, deviations, CAPAs, recalls, or further regulatory actions. Still, it remains a distinct post-market quality signal that must be recorded, assessed, trended, and managed within a defined complaint handling system.

Classification of Complaints

Complaint classification must be driven primarily by risk and patient impact, not administrative convenience or descriptive labels. The classification framework must enable rapid identification of high-risk cases, consistent decision-making, clear escalation criteria, and proportional investigation depth. Poorly designed classification systems typically under-classify risk, delay escalation, and weaken regulatory confidence.

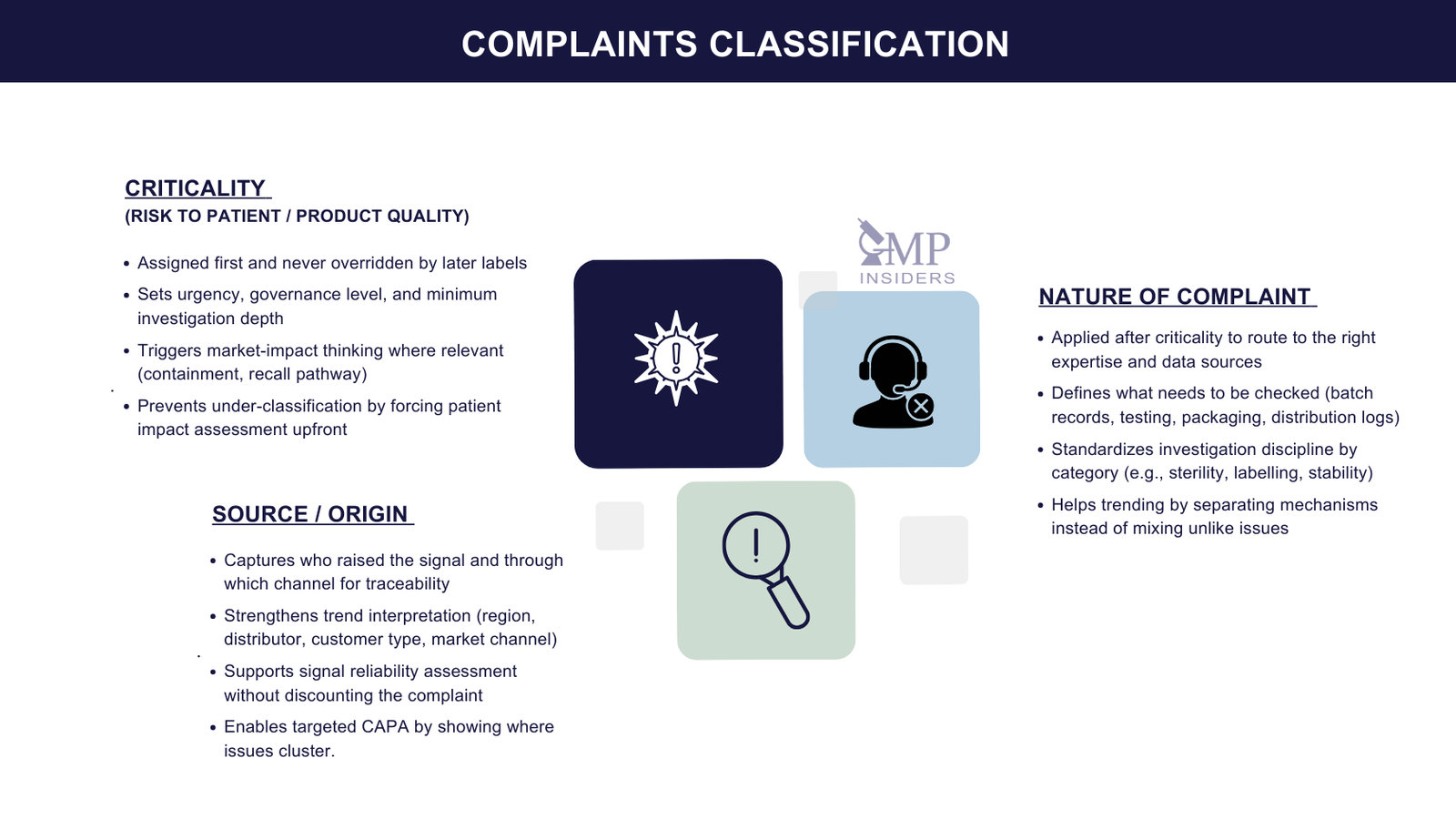

A practical and inspection-defensible classification system considers three pillars:

- Criticality (Risk to Patient / Product Quality) – Primary Determinant

- Nature of Complaint – Supports Technical Routing

- Source / Origin – Supports traceability and trending

Criticality must always take precedence.

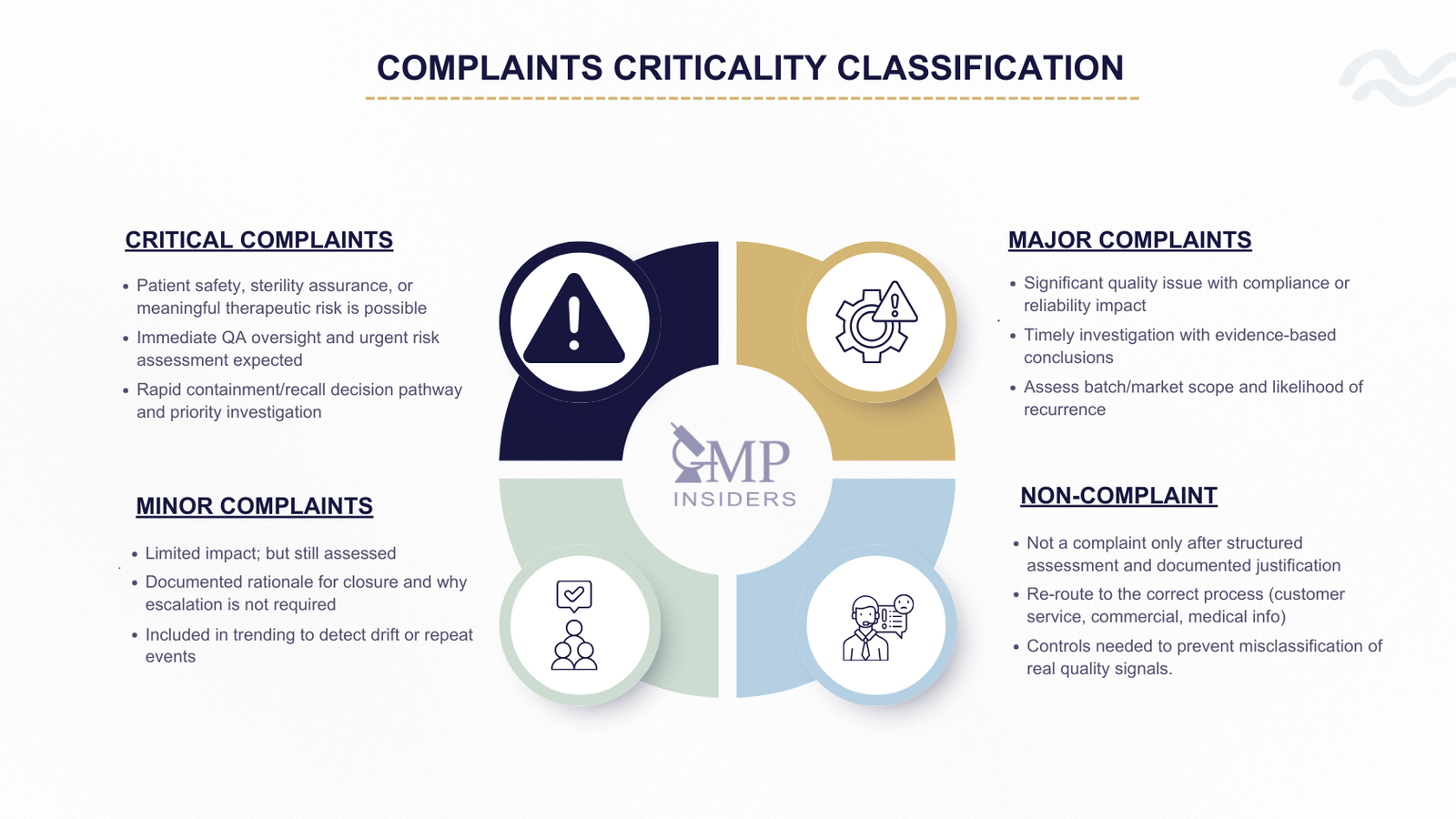

Classification by Criticality (Primary Control)

This classification determines urgency, governance level, investigation depth, and recall considerations. Terms may vary between companies, but the logic must be consistent and justified.

Critical Complaints

Complaints indicating a potential or confirmed risk to patient safety, sterility assurance, or therapeutic performance. Typically include:

- Incorrect strength / incorrect product

- Microbial contamination or sterility assurance failure risk

- Cross-contamination indicators

- Significant label or leaflet errors affecting safe use

- Compromised container closure integrity

- Confirmed or suspected falsified product

- Any defect where use may cause harm

Expected behaviour:

- Immediate QA oversight

- Urgent risk assessment

- Rapid decision on market containment/recall

- Priority investigation

- Senior management involvement

Failure to treat these with urgency is one of the most serious inspection findings.

Major Complaints

Complaints indicating a significant quality issue that may not present immediate patient risk but could compromise compliance, product quality, or reliability. Examples:

- Significant packaging defects

- Repeated manufacturing inconsistencies

- Stability concerns without confirmed failure

- Failures likely to impact product acceptance or compliance

Expected behaviour:

- Timely investigation

- Data-driven justification

- Assessment of potential batch or market impact

- Linkage to CAPA if systemic factors are identified

Minor Complaints

Complaints with limited impact on quality or safety, often cosmetic or perception-based, but still requiring assessment and trending. Examples:

- Minor cosmetic packaging defects

- Isolated handling-related damage

- Non-critical usability concerns

Expected behaviour:

- Documented assessment

- Justified conclusion

- Contribution to trend analysis

Non-Complaint

Cases that, after structured assessment, do not constitute a quality complaint. This requires explicit justification, not informal dismissal.

Examples:

- Enquiries

- Commercial communications

- Misinformation clearly unrelated to product performance

- Handling misused evidence

Improperly rejecting legitimate complaints is a serious regulatory weakness.

Nature of Complaint

Once criticality is established, complaints may be categorised by technical nature to support routing, investigation discipline, and specialist involvement.

Typical categories include:

- Quality attributes and defects (appearance, contamination, particulate, integrity)

- Performance/lack of effect

- Labelling/packaging

- Sterility assurance

- Stability-related concerns

- Logistics/temperature excursion

- Counterfeit / tampering suspicion

- Safety-linked complaints (requiring PV interface)

This classification supports who investigates, not how urgently.

Origin of Complaint

The source of the complaint provides context and trend value:

- Healthcare professionals

- Patients

- Pharmacies/hospitals

- Wholesalers/distributors

- Regulatory authorities

- Internal personnel

This supports signal detection, recurring market themes, regional trends, or reporting reliability assessment.

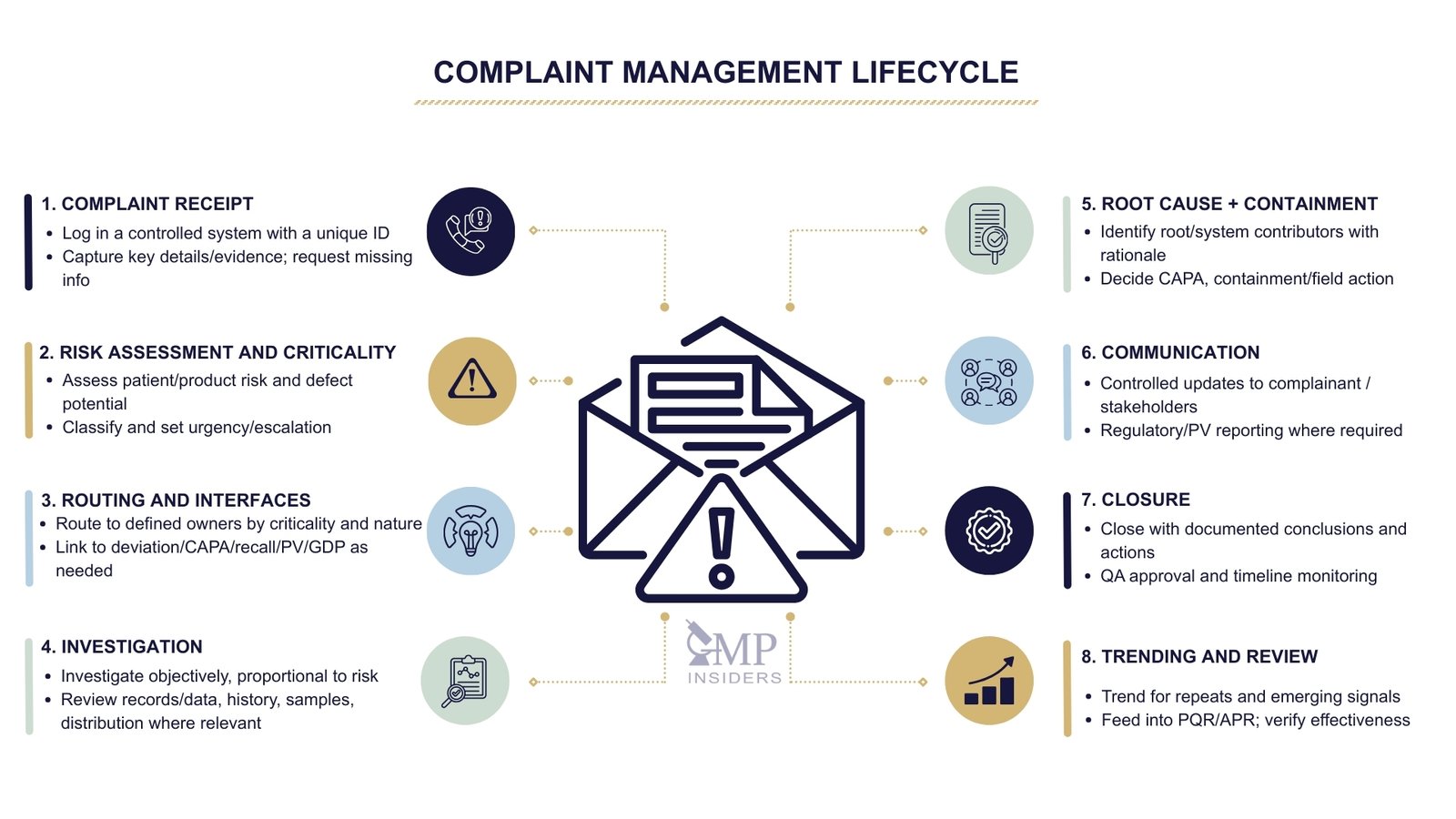

Complaint Management Lifecycle

An effective complaint management system must operate as a controlled, repeatable, and risk-driven process. Authorities consistently expect manufacturers to demonstrate that every complaint is captured, assessed, investigated proportionately, documented objectively, and used for ongoing quality surveillance. The lifecycle must therefore be clearly defined, consistently applied, and under Quality oversight.

The lifecycle below reflects good practice observed in competent organisations and aligns with regulatory expectations.

1. Receipt, Registration, and Completeness Check

Every complaint received must be:

- Acknowledged

- Formally recorded

- Uniquely identified

- Handled under a controlled system

Registration must include:

- Product and batch identification (where available)

- Complainant details

- Description of concern in the complainant’s words

- Date received and person recording

- Any accompanying evidence (sample, images, documentation)

The system must not allow informal handling, selective recording, or discretionary screening outside of a defined process.

Before risk assessment, the information must be made usable and evaluated:

- Whether sufficient information exists to support the assessment

- Whether additional data is required

- Whether a sample retrieval is possible or necessary

- Whether supporting documentation should be requested

Where information is incomplete, structured follow-up is expected. However, lack of complete information does not automatically invalidate a complaint; it must still undergo risk evaluation to the extent possible.

2. Risk Assessment and Criticality Classification

Every complaint must undergo a documented risk assessment to determine:

- Whether the case represents a potential patient risk

- Whether it may indicate a quality defect

- Whether immediate containment or escalation is required

- Whether further distribution should be restricted

- Whether recall consideration is necessary

Classification into Critical/Major/Minor/Non-Complaint must occur here using predefined criteria, not subjective judgment. This determines:

- Urgency of actions

- Level of QA oversight required

- Scope and depth of investigation

- Escalation to senior management

Weak systems either delay this assessment or under-classify risk, both of which are unacceptable from a regulatory standpoint.

3. Routing and System Interfaces

Based on classification and complaint nature, cases must be routed correctly. Typical interfaces include:

- Deviation/non-conformance systems

- CAPA system

- Product Quality Defect/Recall System

- Pharmacovigilance/vigilance systems

- GDP/distribution quality systems

- Change control

- Stability monitoring

- Manufacturing and QC systems

This routing must be defined, not improvised. Authorities frequently criticise systems in which complaints remain isolated and not properly integrated.

4. Investigation

If investigation is warranted, it must be:

- objective

- evidence-based

- proportionate to risk

- scientifically justified

- documented in a structured manner

Expectations include:

- Review of batch manufacturing and packaging records

- Evaluation of test results and batch release data

- Review of deviations, change history, and CAPA related to the product

- Assessment of stability and historical complaint data

- Comparison with retained samples and in-house control samples, where appropriate

- Laboratory investigation where relevant

- Evaluation of distribution and storage history

Regulators commonly reject superficial investigations, unjustified conclusions, or “no manufacturing defect found” statements that lack supporting data.

5. Root Cause Determination and CAPA/Containment Decisions

Where a defect or failure is confirmed or probable, root cause analysis must distinguish between:

- causal factor

- root cause

- systemic contributing factors

Human error cannot be treated as a final explanation without demonstrating why the system allowed it to occur. Tools such as 5-Why, Ishikawa, fault tree, and structured problem-solving methodologies should be applied where appropriate.

Where no root cause can be definitively proven, the rationale must still be scientifically defensible.

SEE ALSO: 6 Steps on How to Perform Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

Based on investigation outcomes, the organisation must determine:

- Whether the complaint is justified

- Whether product quality is compromised

- Whether other batches are at risk

- Whether the product on the market requires a recall or other field action

- Whether CAPA is required

- Whether risk communication is necessary internally or externally

Decisions must be traceable, justified, and aligned with defined governance. Senior QA or executive involvement is expected for higher-risk scenarios.

6. Communication

Communication must be controlled and consistent:

- Response to the complainant, where applicable

- Communication with distributors, partners, or MAH where relevant

- Reporting to regulatory authorities where required

- Alignment with PV/vigilance reporting obligations, where applicable

Inspectors frequently criticise inconsistent or delayed communication.

7. Closure

A complaint can only be closed when:

- Investigation is complete

- Justification is documented

- Decisions and actions are recorded

- CAPA (if applicable) is initiated and assigned

- Risk has been adequately assessed

- QA has reviewed and approved

Closure timing must be monitored. Long-open complaints are interpreted as poor control unless justified.

8. Trending and Periodic Review

Complaint systems must not operate only on a case-by-case basis. Authorities expect:

- Complaint trending

- Identification of recurring themes

- Statistical evaluation where applicable

- Linkage to Product Quality Review / Annual Product Review

- Escalation of emerging signals

Failure to trend complaints is a frequent regulatory criticism.

Governance, Responsibilities, and Quality System Integration

Complaint handling is not an isolated administrative function. It is a core quality system activity that requires defined ownership, disciplined governance, and integration with other QMS elements.

Regulators consistently assess who controls the process, how decisions are made, whether senior management is involved when appropriate, and whether the complaint system actually drives quality improvement rather than simply documenting events.

Ownership and Quality Oversight

Complaint handling must operate under Quality/QA authority. This is not optional. While operational functions may contribute data or perform technical activities, QA must retain oversight and decision power.

A compliant governance model includes:

- Clearly defined process ownership under QA

- Written and approved procedures defining responsibilities

- QA review of each complaint and investigation

- QA approval of conclusions, risk decisions, and closure

- Clear definition of when senior management must be notified or involved

Where complaint processes are owned by commercial, customer service, or supply chain functions without QA control, regulatory confidence is extremely low.

Role Clarity and Functional Participation

Multiple functions contribute to complaint assessment. However, roles must be explicit and standardised, not improvised on a case-by-case basis.

Typical contributors include:

- QA – overall control, decision authority, approval

- Manufacturing / Packaging – process and batch record evaluation

- QC – analytical and laboratory assessment

- Technical / Engineering – technical assessments and equipment-related evaluations

- Stability function – assessment of potential product degradation relevance

- Supply Chain / GDP – assessment of transport, storage, and handling aspects

- Pharmacovigilance / Vigilance – safety signal assessment where applicable

- Regulatory Affairs – regulatory communication where required

Confusion, overlaps, informal delegation, or unclear accountability frequently result in delayed actions, inconsistent conclusions, and inspection deficiencies.

Escalation and Decision-Making Framework

Complaint systems must contain predefined escalation criteria. Decisions such as classifying an issue as critical, initiating a recall evaluation, initiating a field safety corrective action, escalating to executive management, or notifying regulatory authorities must not depend on informal judgement.

Authorities expect:

- Written escalation rules

- Defined governance pathways

- Documented decision-making steps

- Involvement of senior QA and executive management for high-risk cases

- Traceable justification of outcomes

A system without structured escalation is interpreted as uncontrolled.

| Trigger / Signal | Typical Examples | Escalate To | Required Actions | Documentation Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criticality = Critical | Incorrect strength/product; sterility assurance concern; CCI risk; label error affecting safe use; falsified/tampered suspicion | QA leadership + Senior Mgmt | Immediate risk assessment; containment/recall pathway evaluation; priority investigation | Risk assessment rationale; decision log; timelines; approvals |

| Patient harm plausible | Wrong dosing info; contraindication missing; severe misuse risk due to label/leaflet | QA leadership + RA (and PV if safety-linked) | Assess exposure/scope; decision on communications and field action | Impact assessment; communication plan; justification |

| Sterility assurance / microbiological risk | Contamination concern; sterility failure suspicion; integrity breach | QA + Micro/SME + Senior Mgmt (as needed) | Expedite investigation; consider market action; define testing strategy | Technical assessment; investigation plan; data review |

| Counterfeit / tampering suspicion | Pack anomalies; missing security features; supply chain anomalies | QA + Security/SCM + RA | Initiate integrity escalation pathway; containment; authority notification assessment | Chain-of-custody notes; photos/samples; decisions |

| Trend signal / repeat theme | Same defect across cases/batches/markets | QA + CAPA owner | Trigger CAPA; broaden scope; verify effectiveness | Trending output; CAPA linkage; effectiveness plan |

| Manufacturing/control failure suspected | Batch record anomalies; repeated deviation patterns | QA + Manufacturing + QC | Open deviation/NCR; align investigations; cross-reference outcomes | Complaint ↔ deviation linkage; consistent conclusions |

| Recall not initiated despite significant defect | High-severity complaints but “no recall” outcome | QA leadership + Senior Mgmt + RA | Document why recall not warranted; confirm risk controls | Explicit justification; exposure assessment; approval trail |

| Regulatory authority report received | Authority complaint/referral | QA + RA + Senior Mgmt (case-dependent) | Priority handling; align response package; timelines control | Response record; investigation summary; commitments |

Integration with Deviation and Non-Conformance Management

A significant number of investigation deficiencies arise because complaints are handled separately from deviation systems. Proper governance requires:

- Raising deviations / non-conformances when indications of manufacturing or control failure exist

- Ensuring complaint-related deviations follow the same rigorous investigation standards as internal failures

- Ensuring the outputs of deviation investigations link back to the complaint record

- Ensuring consistency between deviation conclusions and complaint conclusions

Authorities frequently identify inconsistencies between complaint files and deviation reports, which undermines credibility.

Integration with CAPA

CAPA must be triggered when systemic weaknesses, repeated complaints, or confirmed product quality issues are identified. Acceptable governance requires:

- Defined criteria for when CAPA is required

- Linkage between complaint data and the CAPA system

- Traceability between complaint investigations and CAPA actions

- Evaluation of CAPA effectiveness

- Prevention of repeated complaint themes

A complaint system that does not generate CAPAs, or generates them rarely, is interpreted as either ineffective or superficial.

SEE ALSO: Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) Plan in GMP

Integration with Product Quality Defect and Recall Management

When complaints indicate potential patient risk or the significance of a quality defect, structured alignment with product quality defect management is expected. This includes:

- Documented assessment of whether a case may warrant market containment

- Evaluation of batch scope and exposure

- Timely initiation of recall or defect management procedures where appropriate

- Alignment between complaint files and recall documentation

Authorities often expect a clear, documented explanation when a recall is not initiated despite significant complaints.

| Complaint Scenario | QMS Element Triggered | When It Must Be Triggered | Mandatory Linkage | Key Output Expected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible manufacturing/control failure | Deviation / Non-conformance (NCR) | Any indication of process, testing, or control failure | Complaint record ↔ Deviation record | RCA and investigation report with aligned conclusions |

| Systemic issue or repeated complaints | CAPA | Repeat trend, confirmed defect, or systemic weakness | Complaint ↔ CAPA (traceable) | CAPA plan, owners, due dates, effectiveness check |

| Potential patient risk / significant defect | Product Quality Defect / Recall process | Critical complaints; serious label, CCI, or sterility concerns; broad market exposure | Complaint ↔ PQD / Recall assessment | Field action decision and documented recall or no-recall rationale |

| Safety-linked information present | PV / Vigilance system | Any adverse event or safety signal requiring PV evaluation | Complaint ↔ PV case | Triage outcome, reporting decision, follow-up plan |

| Distribution/storage/temperature concerns | GDP / Distribution Quality | Excursions, damage, suspected handling or storage failure | Complaint ↔ GDP incident/deviation | Lane assessment, exposure evaluation, disposition rationale |

| Change-related suspicion | Change Control | When complaint plausibly links to a recent change (process, supplier, pack, site, method) | Complaint ↔ Change record(s) | Impact assessment, change effectiveness review |

| Stability relevance | Stability Monitoring | Suspected degradation, shelf-life concerns, storage history issues | Complaint ↔ Stability records | Stability impact assessment, potential studies or actions |

| Investigation indicates product impact | Batch disposition governance | When product quality is questioned for any distributed batch | Complaint ↔ Disposition decision | Clear disposition statement, scope definition, approvals |

Trending, Metrics, and Quality Intelligence

Complaint handling is not limited to managing individual cases. Regulators expect manufacturers to demonstrate that complaint data are used to monitor product performance, detect emerging risks, and support ongoing quality oversight. A system that closes complaints one by one without structured trend analysis is considered reactive and immature.

Trending must be intentional, methodologically sound, risk-oriented, and integrated into broader quality governance.

Purpose of Complaint Trending

Complaint trending must enable:

- Identification of recurring or emerging defect patterns

- Timely recognition of risk signals

- Evaluation of process and product performance in real use

- Monitoring of CAPA effectiveness

- Evaluation of supplier, manufacturing site, and distribution performance

- Contribution to lifecycle knowledge and continual improvement

Trending is not a statistical exercise for reporting. It is a decision-support tool.

What Should Be Trended

Typical trending parameters include:

By criticality

- Number and proportion of Critical, Major, and Minor complaints

- Changes in the severity profile over time

By product and batch

- Complaint rate per product

- Complaint rate normalised to market volume

- Batch-specific spikes or recurring issues

By defect type

- Particulate/contamination-related

- Labelling/packaging

- Stability-related

- Dosing/strength concerns

- Integrity and sterility-related issues

- GDP / transport-related complaints

By geography or market

- Region-specific complaint concentrations

- Country-specific recurring patterns

By source

- Healthcare professionals

- Pharmacies

- Patients

- Regulators

- Distribution partners

Each category supports different insights. A mature organisation uses multiple perspectives rather than relying on a single metric.

Detection of Trends and Signals

A competent complaint system defines how a “trend” is detected, not just that trending exists. Expectations include:

- Predefined alert levels or thresholds

- Rules for repeated similar complaints

- Statistical approaches, where appropriate

- Justification when trends are not acted upon

A signal ignored or recognised only retrospectively reflects poorly on governance.

Performance Monitoring, KPIs, and Compliance Expectations

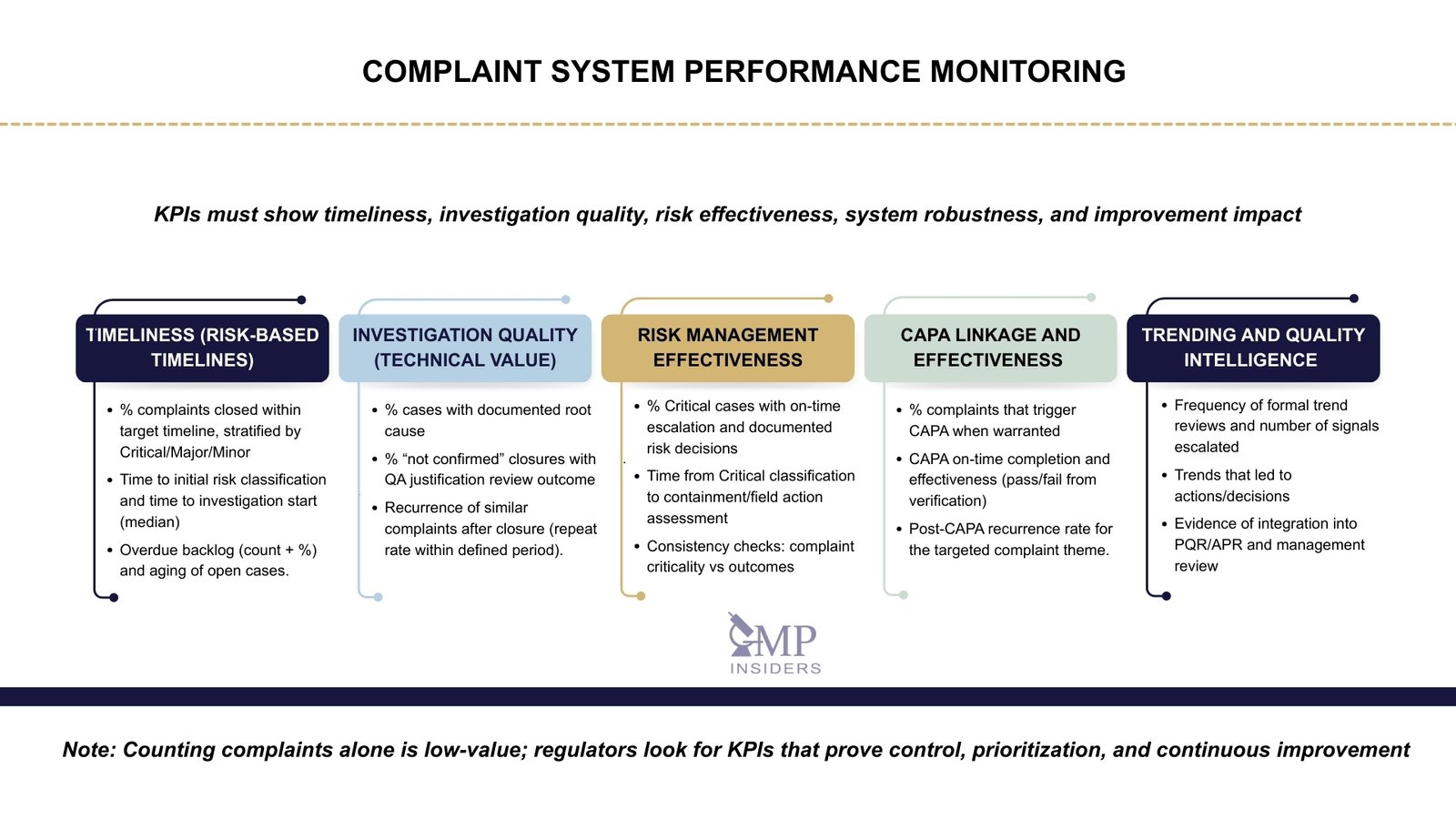

Complaint handling performance must be measurable. Regulators expect manufacturers to monitor the effectiveness of their complaint system using defined indicators, rather than relying on informal judgment or retrospective review. Performance metrics are not a reporting formality; they are evidence of operational control, capacity, and quality system maturity.

KPIs must reflect:

- Timeliness

- Quality of investigations

- Risk management effectiveness

- System robustness

- Contribution to continuous improvement

Metrics that simply count complaints without evaluating system performance have limited regulatory value.

Timeliness Indicators

Authorities consistently focus on whether complaints are addressed within defined, risk-based timelines. Key indicators typically include:

- Percentage of complaints closed within defined timelines

- Median and average closure time, stratified by criticality

- Number and proportion of overdue complaints

- Time to initial risk classification

- Time to investigation initiation

Persistent delay, backlog of open cases, or regular timeline breaches are interpreted as indications of insufficient QA capacity, weak prioritisation, or inadequate governance.

Investigation Quality Indicators

Beyond timeliness, regulators expect companies to evaluate whether complaint investigations demonstrate real technical value. Indicators may include:

- Percentage of complaints with documented root cause (where applicable)

- Proportion of cases closed as “not confirmed” with justification quality review

- Internal quality review findings on investigation depth and completeness

- Recurrence of similar complaints following previously “closed” investigations

CAPA Linkage and Effectiveness

When complaints identify systemic weaknesses, authorities expect effective CAPAs. Relevant performance measures include:

- Percentage of complaints leading to CAPA (where warranted)

- CAPA timeliness

- CAPA effectiveness outcomes

- Recurrence rates of complaint themes following CAPA implementation

If CAPA does not measurably reduce complaint recurrence, the system is not functioning effectively.

Trending and Quality Intelligence Indicators

Trending must demonstrate more than passive reporting. Indicators may include:

- Frequency of formal complaint trend review

- Number of trends identified and acted upon

- Integration of complaint trend outcomes into Product Quality Review / APR

- Senior management review engagement

Authorities may request evidence that trends prompted real decision-making and system improvement.

Regulatory Basis and Expectations

Complaint-handling requirements are explicitly defined in major GMP frameworks. The intent of each is consistent: structured control, documented evaluation, timely, risk-based decision-making, and demonstrable quality oversight.

EU GMP – Volume 4, Chapter 8 (Complaints and Product Recall)

EU GMP requires a documented and effectively implemented system for receiving, recording, investigating, and evaluating complaints. Key expectations include:

- Every complaint must be recorded, assessed, and evaluated to determine whether it relates to a potential quality defect.

- Complaint handling must be under QA responsibility, with a clear definition of roles and decision authority.

- Investigations must be objective, scientifically justified, and supported by appropriate evidence, not assumptions.

- When a potential defect exists, manufacturers must evaluate batch relevance, potential market exposure, and the necessity of a recall.

- Complaint information must interface with recall management, product quality defect procedures, and ongoing product quality review (PQR).

- Records must be retained in a secure, controlled, and retrievable manner.

- Complaints must be trended and evaluated as part of ongoing quality oversight.

US FDA – 21 CFR 211.198 (Complaint Files)

21 CFR 211.198 requires manufacturers to maintain written, approved, and implemented procedures for complaint handling. Core requirements include:

- Written procedures must describe how complaints are received, documented, evaluated, and investigated.

- The Quality Unit must review each complaint to determine whether it represents a possible failure to meet specifications.

- Investigations must be conducted where warranted and must be adequately documented, including conclusions and supporting data.

- If no investigation is conducted, this must be scientifically justified and documented.

- Complaint files must be maintained in an accessible and controlled manner.

- Links to CAPA, manufacturing evaluation, and field actions must be demonstrable.

FDA inspection experience shows repeated instances in which companies conclude “no manufacturing defect” without evidence, conduct weak investigations, or fail to link complaints to broader system performance. These are typically unacceptable.

EU GDP – Guidelines on Good Distribution Practice of Medicinal Products for Human Use (2013/C 343/01)

Where complaints involve storage, transport, handling, temperature excursions, product integrity, or suspected falsification, GDP expectations apply in addition to GMP obligations. Authorities expect:

- Defined interfaces between GDP and GMP systems, ensuring structured information flow.

- Risk-based evaluation of temperature excursions, handling damage, compromised packaging, and suspected tampering or falsification.

- Clear responsibility allocation between the manufacturer, MAH, wholesalers, and distributors.

- Traceability and documented investigation across the distribution chain under quality oversight.

GDP-related complaints must not be treated solely as commercial or logistics issues. If product quality may be affected, they remain GMP-relevant quality risk signals.

Pharmacovigilance / Vigilance Expectations

When complaints include potential safety information, systems must demonstrate controlled linkage to pharmacovigilance/vigilance processes.

For medicinal products, this aligns with EU GVP Module VI and FDA 21 CFR 314.80 / 600.80; for devices/combination products, EU MDR 2017/745 and FDA 21 CFR 803 apply.

Authorities expect:

- Defined criteria to recognise safety-relevant complaints

- Immediate transfer to PV / vigilance with preserved timelines and traceability

- Alignment between complaint records and safety databases

Complaint systems and safety systems must operate as an integrated framework, not independently.

FAQ

Do All Complaints Require a Full Investigation?

No. Not every complaint requires the same level of investigation, but every complaint requires a structured assessment and documented justification. A risk-based approach determines whether a full investigation, a limited evaluation, or no investigation is warranted.

However, “no investigation” decisions must be the exception, not the norm, and must be defensible with evidence, not convenience. Authorities routinely question cases where investigations are declined without a clear rationale.

What if No Batch Number or Product Identifier Is Provided?

A missing batch number does not invalidate a complaint. The company must still assess risk based on the available information, supported by historical data, distribution information, and contextual evidence.

Where possible, additional details should be requested from the complainant. Regulators expect organisations to do “what is reasonable” to assess risk, not dismiss complaints based on incomplete information.

How Should Repeated Minor Complaints Be Handled?

Repeated minor complaints may indicate a significant trend, even if each case appears low-risk individually. Authorities expect structured trending to detect accumulation effects. If recurrence is observed, escalation and CAPA consideration become appropriate. Failure to recognise repeated low-level signals is a common criticism in inspections.

When Is Senior Management Expected to Be Involved?

Senior involvement is expected for critical complaints, potential recalls, significant systemic risk, or scenarios with reputational or regulatory impact. Escalation criteria must be predefined and consistently applied. Authorities often review records to ensure escalation truly occurs in practice. The absence of executive engagement in high-risk cases signals weak-quality leadership.

What if the Complaint Concerns a Product Manufactured by a CMO?

The Marketing Authorisation Holder and manufacturer remain responsible for investigating complaints, even when activities are outsourced. Responsibilities must be contractually defined in Quality Agreements.

Authorities expect clear communication pathways, shared data access, and aligned decision-making. “CMO responsibility” is never a valid excuse for weak complaint handling.

Can Complaints Be Closed Before CAPA Effectiveness Is Confirmed?

In most cases, complaint closure reflects completion of investigation and decision-making, while CAPA may continue under separate governance. However, decisions must explain how risk is controlled pending CAPA completion. Authorities expect appropriate interim controls. Uncontrolled closure without a credible justification is unacceptable.

Are Complaint Systems Evaluated Differently for High-Risk vs Low-Risk Products?

Yes, authorities expect proportionality aligned with product risk, but proportionality cannot be used to justify weak control. High-risk products (e.g., sterile, parenteral, inhalation) require more aggressive escalation and investigation standards. Lower-risk products still require disciplined governance and trending. The principle is proportional control, not selective compliance.

Final Thoughts

Complaint management should never be considered as a support function or an administrative obligation. It is a core expression of quality system maturity. Regulators evaluate complaint handling because it reliably exposes an organisation’s actual capability to recognise risk, apply technical discipline, and act with accountability when products are in patients’ hands.

A system that merely records and closes complaints is insufficient. The expectation is a controlled, risk-based, and evidence-driven framework that demonstrates understanding of both product performance and organisational responsibility.

Effective complaint handling requires defined ownership under QA, clear governance, proportionate investigation depth, credible documentation, timely escalation, and meaningful integration with deviations, CAPA, pharmacovigilance, GDP, recall processes, and lifecycle management.

Trending, metrics, and quality intelligence must convert complaint data into actionable learning rather than retrospective reporting. Weakness in any of these areas is interpreted not as an isolated failure but as a deficiency in quality leadership and compliance culture.

Ultimately, a mature complaint system protects patients, strengthens regulatory confidence, and supports sustained operational reliability. Organisations that treat complaints as quality intelligence rather than an administrative burden demonstrate control, transparency, and genuine commitment to GMP principles.