Software validation vs verification refers to the distinction between confirming that a software system has been correctly built according to approved specifications (verification) and confirming that it is suitable for its intended use in its operational GMP environment (validation). Both are required activities under EU GMP Annex 11 and FDA 21 CFR Part 11, but they address different regulatory questions and cannot be treated interchangeably.

The distinction between the two is often misunderstood. While both validation and verification are integral to the software lifecycle, they represent separate activities with different objectives and regulatory expectations. Misinterpretation of these concepts can lead to insufficient documentation, inadequate testing, or over-validation of low-risk systems.

In GMP, software verification confirms that a system has been developed and configured according to predefined specifications, ensuring technical correctness and consistency with design requirements. Software validation demonstrates that the verified system is suitable for its intended use and performs reliably in the actual GMP process where it is implemented.

In this article, we outline the difference between software validation and verification, their respective roles within GMP and FDA frameworks, and how they are applied in practice following EU GMP Annex 11, 21 CFR Part 11, and GAMP 5 guidance.

What Is Software Verification

Software verification is the documented process of confirming that a software system, or any of its components, has been developed, configured, and tested according to predefined specifications and design requirements. It provides objective evidence that the system has been built correctly, answering the question: “Did we build the software right?”

Within the GMP framework, software verification ensures that the design and development outputs of a computerized system match the approved user and functional requirements. It confirms technical correctness, configuration accuracy, and alignment with design intent before the system is ever introduced into operational use.

Regulatory guidelines such as EU GMP Annex 11, FDA 21 CFR Part 11, and GAMP 5 define verification as a structured activity that supports validation and demonstrates technical control over the software lifecycle. Verification takes place before any validation activities and builds the foundation upon which validation can occur.

In practice, verification confirms compliance with approved specifications, configuration documents, and test requirements. It ensures that every feature, configuration, and system interface has been reviewed and tested under controlled, traceable conditions.

Typical Software Verification Activities

Software verification activities are structured and documented to confirm that the system has been built correctly and aligns with approved specifications. These activities focus on technical correctness, configuration accuracy, and traceability to requirements, without yet assessing real-world usability.

All verification results are documented through approved test protocols, traceability matrices, and summary reports to provide objective, audit-ready evidence of technical compliance:

- Review and approval of specifications – ensuring clarity, completeness, and testability of User Requirements (URS), Functional Specifications (FS), and Design Specifications (DS).

- Design and configuration review – evaluating design documents, database structures, or configuration settings to confirm alignment with requirements.

- Testing at different levels:

- Unit Testing – verifying individual components or functions

- Integration Testing – confirming that components work together correctly

- System Testing – ensuring that the entire system functions according to specifications

- Installation Qualification (IQ): confirming correct installation, version control, and infrastructure alignment.

- Operational Qualification (OQ): testing whether the system operates as intended under controlled, predefined conditions.

All verification results are documented through approved test protocols, traceability matrices, and summary reports to provide objective, audit-ready evidence of technical compliance.

Application in GMP Systems

In the pharmaceutical industry, software verification applies to both custom-developed systems and configured commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) solutions such as LIMS, MES, QMS, and environmental monitoring systems. The approach may differ, but the objective remains the same: to confirm that the system has been built and configured exactly as specified before it is introduced into operational use.

For COTS systems, verification often includes a review of vendor-supplied documentation (e.g., IQ/OQ protocols, configuration guides, test evidence). However, this supplier evidence must be critically assessed and supplemented to confirm that it aligns with the regulated company’s own configuration and intended use.

For custom-developed or heavily configured systems, verification relies on internally executed testing and documentation, performed under a formally approved V&V plan, with full traceability back to the URS and FS.

In both cases, verification is not optional and cannot be skipped or assumed based on vendor trust, but a regulatory expectation and the technical prerequisite for validation.

| System Type | Verification Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| COTS systems (e.g. LIMS, MES, QMS, EMS) | Review and use of vendor IQ/OQ and configuration documentation |

Vendor evidence must be assessed, not accepted blindly Supplement vendor testing where gaps exist Must reflect company-specific configuration and workflows Internal approval under controlled process Intended use must be demonstrably covered |

| Custom-developed systems | Internally executed verification testing |

Testing performed against URS and FS Formal V&V plan required Full traceability required Complete internal documentation No reliance on vendor assumptions |

| Heavily configured systems | Hybrid approach (vendor + internal testing) |

Configuration drives verification scope Focus on configuration accuracy Misalignment is a frequent audit finding |

Risk-Based Consideration in Software Verification

The level of verification effort must be proportionate to the system’s GxP impact and data integrity risk, not standardized across all systems. EU GMP Annex 11, GAMP 5, and FDA CSA all emphasize that verification should be scaled based on criticality, not system size or vendor claims.

- High-impact systems (e.g., MES, LIMS, QMS modules used for batch release or regulatory decisions) require formal, fully documented verification, supported by traceability matrices, executed protocols, and QA review.

- Low-risk systems (e.g., tools used only for monitoring or non-decision-making support) may follow a simplified verification approach, using structured vendor evidence or streamlined internal testing, provided this reduction is formally justified, approved, and documented.

Verification establishes the technical foundation for validation. Only when a system has been verified against its specifications can it proceed to validation, where its fitness for intended use is demonstrated under real operating conditions.

What Is Software Validation

Software validation is the documented process of confirming that a verified software system performs as intended when used in its actual operating environment. It provides evidence that the system is fit for its intended use, answering the question: “Did we build the right software?”

Under GMP, software validation ensures that the system consistently supports compliant processes, preserves data integrity, and performs reliably during routine operation. This includes not only functional accuracy but also user roles, approval flows, audit trails, traceability, and decision control.

According to EU GMP Annex 11, computerized systems used in GMP processes must be validated to demonstrate accuracy, reliability, and consistent intended performance. Similarly, FDA 21 CFR Part 11 requires validation of systems managing electronic records and signatures to ensure data integrity and traceability.

Validation extends beyond technical verification; it confirms that the system supports the specific process for which it was implemented and that it maintains compliance throughout its operational life. In this context, validation is not a one-time event but a continuous lifecycle activity, supported by change control, periodic review, and revalidation where necessary.

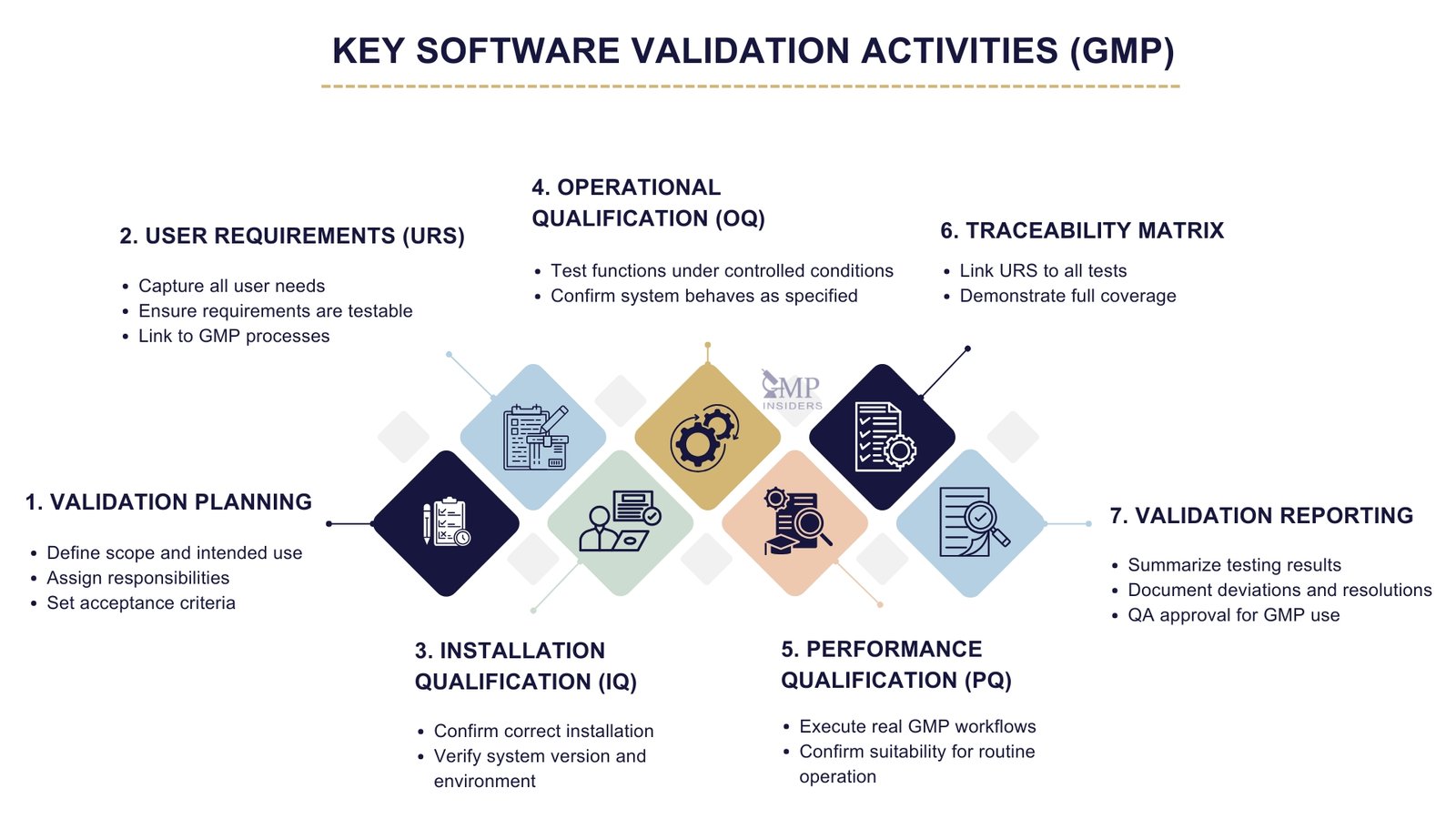

Key Software Validation Activities

Software validation follows a structured, lifecycle-based approach as defined in GAMP 5, ensuring that the system is not only technically correct but also fit for its intended GMP use.

Typical validation activities include:

- Validation Planning: Preparation of a Validation Plan defining scope, responsibilities, testing approach, acceptance criteria, and documentation requirements.

- User Requirements Specification (URS): Verification that all user needs are captured and testable.

- Qualification Phases:

- Installation Qualification (IQ): Confirms installation according to manufacturer specifications.

- Operational Qualification (OQ): Demonstrates correct operation of all functions under controlled conditions.

- Performance Qualification (PQ): Confirms the system performs as intended in its routine, GMP-relevant environment.

- Traceability Matrix: Links each requirement to test coverage and results to prove full alignment.

- Validation Reporting: Preparation of a Validation Summary Report documenting all testing activities, deviations, and final approval for operational use.

Application in GMP Systems

Software validation is mandatory for any computerized system that has a direct or indirect impact on product quality, patient safety, or data integrity. This applies equally to custom-built solutions and configured commercial systems (COTS) such as:

- LIMS – Laboratory Information Management Systems used for analytical data and CoA generation

- MES / EBR – Manufacturing Execution or Electronic Batch Record systems used for batch execution and release decisions

- QMS Platforms – Systems used for deviation, CAPA, complaint, and training records

- Environmental Monitoring Systems (EMS) – Systems monitoring critical parameters such as temperature, humidity, or differential pressure

While vendor documentation and test evidence may support validation, it never replaces the regulated company’s responsibility to validate the system against its own specific intended use.

Validation depth must reflect the system’s regulatory impact, data integrity risk, and criticality of decision-making within the business process, not system complexity or software size.

| System Type | GMP Use | Validation Focus |

|---|---|---|

| LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System) | Management of analytical data and CoA generation | Data integrity, calculations, approvals, audit trails |

| MES / EBR (Manufacturing Execution / Electronic Batch Records) | Batch execution and release decisions | Process control, decision logic, electronic signatures |

| QMS Platforms | Deviations, CAPA, complaints, training records | Workflow enforcement, traceability, role segregation |

| Environmental Monitoring Systems (EMS) | Monitoring critical parameters (e.g. temperature, humidity, DP) | Alarms, data trending, limit enforcement |

| Custom-built systems | Company-specific GMP workflows | Intended use testing, full lifecycle validation |

| Configured COTS systems | Standard software adapted to GMP use | Configuration-based validation, focused PQ/UAT |

Lifecycle and Ongoing Validation

Software validation is not a one-time activity. Once a system is placed into use, it must be continuously maintained in a validated state throughout its operational lifecycle. Regulatory expectations from EU GMP Annex 11, FDA 21 CFR Part 11, and GAMP 5 require that the validated status is preserved through controlled oversight, documented review, and risk-based revalidation when necessary.

This ongoing assurance is maintained through:

- Formal Change Control: Every change to the system (configuration, upgrade, patch, integration) must undergo impact assessment to determine whether re-verification or revalidation is required.

- Periodic Review: Regular evaluation of system performance, deviations, audit trails, backup status, and alignment with current procedures and regulations.

- Defined Revalidation Triggers: Mandatory revalidation when significant changes occur, such as process updates, regulatory changes, major incidents, or integration with other critical systems.

If validation is not actively maintained, the system is no longer considered validated, even if it once was.

Difference Between Software Verification and Validation

Software verification and validation are both essential activities within the software lifecycle, but they serve different objectives, occur at different stages, and provide distinct types of assurance. Understanding the difference between software validation and verification is critical because they do not address the same question, and conflating them can lead to regulatory non-compliance.

Verification confirms that the system has been built correctly according to approved specifications and design logic. It ensures technical accuracy, configuration control, and correct implementation before the system is exposed to real users or live data.

Validation, by contrast, confirms that the verified system is fit for its intended use in its operational GMP environment. It ensures the system supports compliant workflows, protects data integrity, and performs reliably under real working conditions.

Both must be completed, but in the correct order and with clear distinction in scope and purpose.

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Purpose | Confirms the system is built correctly according to approved specifications | Confirms the system is fit for its intended use in real GMP operation |

| Primary Question | Did we build it right | Did we build the right system |

| Nature of Activity | Static assessment (review, inspection, IQ/OQ) | Dynamic assessment (UAT/PQ under real-use conditions) |

| Timing | Performed before system is released for operational use | Performed after verification, just before go-live, and maintained throughout system use |

| Focus | Technical correctness and configuration accuracy | Operational suitability, workflow reliability, and data integrity |

| Responsibility | Validation engineer, IT, or implementation team with QA oversight | QA and process owner hold final approval authority |

| Regulatory Risk Focus | Prevention of design and configuration errors | Detection of real-use gaps that could affect compliance or patient safety |

| Typical Outcome | Technical assurance: system is correctly implemented | Operational assurance: system is trusted for regulatory decision-making |

Practical Examples: Software Validation vs Verification

The contrast between verification and validation becomes most evident when applied to real systems. The following examples illustrate how both activities occur in practice, and why they cannot replace each other.

Example 1 – LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System)

Verification

- Each calculation formula, test template, and result rounding rule is confirmed against the Functional Specification.

- Instrument interfaces are checked to ensure correct data mapping and secure transfer.

- Role permissions are reviewed to ensure analysts cannot approve their own data → The system behaves exactly as specified on paper.

Validation

- A real QC analyst performs a complete test cycle: sample login, analysis, review, approval, CoA generation, under controlled but realistic conditions.

- The full process is observed for data integrity, traceability, audit readiness, and alignment to SOPs.

→ It is confirmed that the system actually supports compliant laboratory operation without procedural or integrity gaps.

Example 2 – MES (Manufacturing Execution System)

Verification

- Batch manufacturing rules, hold-point logic, interlocks, and material status checks are tested step-by-step against configuration requirements.

- HMI instructions and deviation triggers are confirmed to fire exactly as defined in the design documentation → The logic and decision gates work technically correct.

Validation

- A real batch scenario is executed as PQ, with realistic material status, real approval roles, and controlled exception handling.

- Focus is on process flow correctness, electronic batch record integrity, and no possibility of bypassing critical controls → It confirms the system supports actual, compliant production flow.

Example 3 – QMS / Deviation & CAPA Software

Verification

- All workflow stages (initiation, investigation, review, approval, closure) are tested against defined business rules.

- User profiles are checked to ensure proper role-based access and segregation of duties → The configuration is technically accurate according to the system design.

Validation

- A real deviation case is executed with full lifecycle, including investigation, root cause, CAPA linkage, and closure approval.

- Confirmed that the system supports compliant documentation flow, escalation logic, and auditability exactly as used in practice → It proves the system supports real inspection readiness and traceability, not just theoretical logic.

Verification and Validation in Software Testing

In software testing, verification and validation (V&V) occur at different stages of the software lifecycle.

Verification focuses on confirming whether the software has been built correctly according to its documented specifications.

Validation focuses on confirming whether the software is suitable for its intended use and performs correctly under real operational conditions.

This distinction is critical in regulated environments, because verification and validation in software testing with example is not only a best-practice concept, it is a GMP and FDA compliance requirement. Testing does not start with “Does it work?” but with “Was it built correctly?” before moving to “Can it be trusted in use?”

How Testing Phases Map to V&V

Verification and validation are not defined by which testing technique is used, but by the intent and timing of the activity.

- Verification activities are executed to confirm correctness before operational use. Examples include reviewing the URS or FS, performing unit, integration, or system testing, and executing IQ/OQ under controlled test conditions.

- Validation activities are executed to confirm suitability for real use. The primary example is User Acceptance Testing (UAT) or Performance Qualification (PQ), where the system is tested under realistic, process-driven conditions with actual end-user roles.

This perspective aligns with GAMP 5, FDA CSA, and both Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11, where the purpose of testing, not the test type, defines whether it is verification or validation.

| Activity | Type | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Reviewing URS or FS | Static | Verification |

| Code or configuration review | Static | Verification |

| Unit or integration testing | Dynamic | Verification |

| Functional system testing | Dynamic | Verification |

| UAT or PQ execution | Dynamic | Validation |

Static vs Dynamic Testing

Static testing refers to activities performed without executing the software. It is closely aligned with verification and includes reviews of the URS, FS, configuration settings, design documents, and qualification protocol content. These activities allow early detection of design flaws and inconsistencies before operation.

Dynamic testing involves executing the software with real or simulated input. Some dynamic testing, such as system testing during OQ, still falls under verification because it is controlled and specification-focused. However, once the purpose shifts to demonstrating intended use under real operational conditions, such as in UAT or PQ, it becomes validation.

Typical Activities and Their Purpose

Verification activities focus on confirming technical correctness before operational use. These typically include:

- Reviewing and approving the User Requirement Specification (URS) and design documentation

- Performing unit, integration, or system-level testing under controlled conditions

- Executing Installation Qualification (IQ) and Operational Qualification (OQ)

- Building and maintaining a traceability matrix to ensure full test coverage

Validation activities focus on confirming that the system is suitable for its intended GMP use. These typically include:

- Executing User Acceptance Testing (UAT) or Performance Qualification (PQ) with real users and real workflows

- Confirming proper role-based access, approval sequences, audit trails, and decision integrity during live process simulation

- Documenting final QA release for operational use

- Revalidating based on change control, regulatory updates, or significant incidents

Why V&V Is Essential in Regulated Environments

Verification and validation are not quality “best practices”, they are mandatory regulatory expectations. Both EU GMP Annex 11 and FDA 21 CFR Part 11 require companies to provide objective evidence that GxP software has been built correctly and performs as intended in its real operating environment.

Verification ensures that no technical or configuration errors are introduced before the system is placed into operation. Validation ensures that the system operates reliably within the actual GMP workflow, supporting correct decisions, compliant behavior, and data integrity during daily use.

Regulators make a clear distinction in terminology, and FDA software verification and validation guidance repeatedly stresses that one cannot replace the other. A system that is only verified may still fail in actual use. A system that is only validated without prior verification cannot be trusted technically.

Correct execution of both V&V activities is therefore fundamental to inspection readiness, batch release decisions, and data integrity assurance.

Why Software Verification and Validation Are Fundamental in GAMP 5–Aligned GMP Systems

GAMP 5 provides the accepted industry framework that defines how verification and validation must be applied across the entire computerized system lifecycle. It introduces the V-model, where the left side represents specification and design, and the right side represents testing and qualification.

- On the left side of the V-model, activities such as URS, FS, DS, and risk assessment are defined; these are the reference points against which verification is executed.

- On the right side, testing activities such as IQ, OQ, and PQ confirm alignment to those specifications: IQ and OQ are verification activities, while PQ is validation, because it demonstrates suitability for real GMP use.

GAMP 5 further enforces a risk-based approach, meaning the depth of verification and validation must be proportionate to the potential impact on patient safety and product quality, not driven by system complexity or vendor classification alone.

This is why GAMP 5 remains the core reference during regulatory inspections — it offers structured justification, traceability, and lifecycle evidence that support both technical verification and operational validation in a controlled, defensible manner.

Related Article: GAMP 5 in CSV

How Validation & Verification Differ from Traditional IT Testing

In traditional IT environments, testing is primarily focused on verifying whether the software functions correctly from a technical perspective. However, GMP-regulated verification and validation extend far beyond functional correctness; they must demonstrate complete operational control, regulatory compliance, and data integrity protection.

Key differences include:

- GMP-level V&V must confirm operational suitability, not just technical performance. A system that “works” functionally but does not align with SOPs, traceability requirements, or approval workflows fails validation.

- Bypassing or overriding critical controls must be impossible, even unintentionally. User restrictions, role permissions, and enforced approval chains are evaluated during validation, not only configuration.

- Data integrity is central; V&V activities must confirm that records, audit trails, and signatures are accurate, complete, and tamper-evident at all times.

- Validation is not a one-time event: the system must remain in a validated state through ongoing change control, periodic review, and revalidation where required

- Evidence must be fully documented, traceable, and retrievable during inspection: post-event reconstruction is unacceptable and seen as a major data integrity red flag.

This is why GMP software validation cannot be treated as conventional IT testing; it is a regulated, lifecycle-driven assurance activity, not just a functional quality control step.

Documentation and Audit Expectations

Verification and validation activities are only considered compliant if they are fully documented, traceable, and inspection-ready at all times. Regulators expect documentation to demonstrate not just that testing was performed, but that it was planned, justified, correctly sequenced, and approved by Quality.

Key documentation expectations include:

- A traceability matrix linking each requirement to test coverage and evidence, this is often the first document requested during an audit

- Clear separation between verification and validation activities, with IQ/OQ completed and approved before PQ or UAT

- Preapproved protocols, no ad-hoc or handwritten test execution without prior QA approval

- Formal validation report or QA release statement, explicitly confirming the system is approved for GMP use

- Controlled change management, with revalidation triggers clearly defined for upgrades, process changes, or regulatory impact

- Evidence must be contemporaneous; Inspectors reject documentation that appears prepared retrospectively (“for the audit”)

Inspectors will not tolerate assumptions, verbal justification, or undocumented rationale. Only documented evidence is defendable, and only when it proves both verification and validation have been executed correctly and distinctly.

See Also: Good Documentation practices in Pharma

Planning and Executing V&V Activities

Effective verification and validation do not start with testing; they start with planning. Regulators expect that V&V is intentional, risk-based, and traceable from the very beginning of the system lifecycle, not just a technical exercise at the end. This means that what will be verified, what will be validated, how it will be judged, and who is responsible must be clearly defined before execution begins.

Defining Scope, Criticality, and Acceptance Criteria

The first step is to determine what exactly is in scope, including which process areas, data flows, users, and regulatory functions are impacted.

This is followed by a formal criticality assessment, establishing whether the system affects:

- Batch release or GxP decisions

- Regulated electronic records or signatures (FDA 21 CFR Part 11 impact)

- Data integrity, traceability, or auditability

- Patient safety or product quality

Risk level defines the depth of V&V required – not system size, not vendor claims.

Only after scope and risk are defined should acceptance criteria be finalized, and these must be documented and approved before any testing begins. Acceptance criteria cannot be written after results are seen. This is one of the most common FDA 483 findings.

Planning

A V&V Plan is drafted as a controlled and approved document, typically authorized by QA before execution begins. It defines exactly how verification and validation will be performed, and in what sequence, ensuring all activities are risk-based, intentional, and defensible during inspection.

A robust V&V plan specifies:

- Scope and system boundaries

- Which activities are verification (e.g., URS/FS review, IQ, OQ)

- Which activities are validation (e.g., UAT, PQ, process simulation)

- Roles and responsibilities, including which activities require QA approval

- Documentation expected at each lifecycle stage

- Criteria for final system release into GMP use

A traceability matrix is a mandatory compliance tool; it links each user requirement to its respective verification and validation evidence and is often the first document requested by inspectors to evaluate lifecycle control.

Core Documentation Requirements

A complete and defendable V&V package normally contains:

- URS (User Requirement Specification): Defines process needs, must be written by process owner, not IT

- FS / DS (Functional / Design Specifications): Technical interpretation of URS, defines how every requirement is implemented

- Test Protocols (IQ, OQ, PQ / UAT): Preapproved, never handwritten “as executed” on the fly

- Deviation Log: Every deviation must be explained, assessed, and either accepted or corrected

- Validation Report / Final QA Statement: The single official decision: the system is approved or not approved for GMP use

Maintaining the Validated State

Regulators expect the system to remain validated, not just validated once.

This is achieved through:

- Formal change control: Every change, update, or patch is impact-assessed before implementation, determining whether re-verification or revalidation is required

- Scheduled periodic review: Checking audit trails, deviations, backup results, open CAPAs, SOP alignment

- Defined revalidation triggers, including:

- major upgrades or new functionality

- integration with new systems

- regulatory requirement changes

- findings during audit or incident investigation

A system that was once validated but not maintained under these principles is no longer considered validated in the eyes of an inspector.

Regulatory Framework and Expectations

Regulatory authorities do not define V&V as an IT best practice; they define it as a compliance obligation. Both EU GMP Annex 11 and FDA 21 CFR Part 11 explicitly require that computerized systems used in GxP activities must be validated with documented evidence that they perform accurately, consistently, and as intended.

EU GMP Annex 11 states that “computerized systems used in GxP activities must be validated” and remain under a controlled lifecycle, with continuous review, change management, and risk reassessment.

FDA 21 CFR Part 11 requires companies to demonstrate that systems used to create or manage electronic records are validated to ensure accuracy, reliability, consistent performance, and integrity of data, not just at go-live, but at all times during use.

Related Article: Annex 11 vs 21 CFR Part 11: Comparison and Requirements

EU GMP Annex 11 (Current Official Version)

EU GMP Annex 11 requires that computerized systems used in GxP activities are validated and maintained under a controlled lifecycle. It expects clear separation of verification and validation activities, with verification confirming correct configuration against specifications, and validation confirming that the system performs as intended in real operational use.

The guidance explicitly requires risk-based justification, traceability from requirements to testing, and ongoing control measures such as change management and periodic review. Annex 11 does not accept a one-time validation; the system must remain validated for as long as it is in use.

Draft Annex 11 (Ongoing Revision – Future Direction)

The draft revision of Annex 11, aligned with the consultation linked to Chapter 4 and the upcoming Annex 22 on artificial intelligence, places stronger emphasis on supplier governance, cloud service oversight, embedded quality risk management, data integrity, and continuous validation strategy.

While the current version already requires lifecycle control, the draft introduces more prescriptive expectations on traceability, accountability, and proof of intended use testing. The revision moves away from interpretation-heavy wording toward explicit operational control of risk and verification/validation discipline, closing the gaps commonly exploited in audits today.

FDA 21 CFR Part 11

FDA 21 CFR Part 11 requires that electronic records and electronic signatures are trustworthy, reliable, and equivalent to paper-based records. The regulation does not merely require software to be tested — it requires evidence that the software has been verified to be correctly configured and validated to perform consistently as intended during routine GMP operations.

This is why U.S. FDA inspectors frequently ask: “Show me the evidence that your system was validated for how you actually use it.” Verification alone is not sufficient — FDA expects full validation and lifecycle maintenance to ensure ongoing trust and data integrity.

GAMP 5

GAMP 5 provides the industry-accepted framework for applying Annex 11 and 21 CFR Part 11 requirements using a lifecycle- and risk-based approach. It defines the V-model, where verification activities correspond to the left side (requirements, specifications, design) and validation activities correspond to the right side (testing, qualification, acceptance for live use).

GAMP 5 reinforces that documentation alone is not compliance, only proven fitness for intended use, supported by traceable evidence and controlled change management, satisfies regulatory expectations.

FDA CSA

The Computer Software Assurance (CSA) guidance from FDA clarifies that regulated companies should not focus on generating excessive documentation, but on providing assurance that the system will protect patient safety and product quality during real use.

CSA reinforces the need to separate verification (“is it built correctly?”) from validation (“is it suitable for its intended process use?”) and instructs industry to focus validation on functions that directly impact compliance or patient risk.

It supports streamlined testing for low-risk functions, but expects formal documented evidence for high-risk use cases, not reduced compliance, but smarter, risk-based validation.

See Also: Key Differences Between CSV and CSA

FAQ

Can Software Be Considered Validated if Verification Was Not Fully Completed First?

No. Verification must be completed before validation because it confirms that the system was built and configured according to approved specifications. If verification is skipped or only partially executed, validation evidence is automatically compromised, even if test results appear correct.

Regulators frequently reject validation where IQ/OQ was incomplete or not traceable to final testing. Validation without proper verification is seen as trust without technical proof, which is unacceptable in a GMP environment.

How Does Failure to Separate Verification From Validation Create Regulatory Risk?

When companies merge verification and validation into one activity, they eliminate the ability to prove whether the system was built correctly before being tested for intended use. This leads to loss of traceability, making it impossible to show controlled progression from configuration to operational readiness.

Inspectors interpret this as process immaturity or risk blindness. In some cases, it has led to immediate system shutdown and remediation orders.

Can a System Be Validated Based Purely on Successful UAT?

No. UAT is only a part of validation and assumes verification is already complete. If UAT is performed while the configuration has not been fully verified, the results are operationally biased and not technically confirmed.

Inspectors frequently find that teams “validated” a system that ran correctly for users, but fundamentally misconfigured critical fields or permissions. Purely business-driven validation without technical verification is a recurring FDA 483 observation.

Can a System Still Be Compliant if Only the High-Risk Functions Are Validated?

Yes, if fully justified and documented under a formal risk-based approach. This is aligned with both GAMP 5 and FDA CSA. However, the risk assessment must be traceable and defensible, not assumed. Complete exclusion of moderate-risk functionality without justification is interpreted as validation avoidance, which is viewed negatively in inspections.

How Does Validation Differ When the Software Affects Batch Release Decisions?

For batch-relevant systems such as MES or LIMS, validation must confirm controlled decision chains, electronic signature security, and no possibility to bypass critical steps or alter records retrospectively. Assurance must extend beyond functional accuracy, it must protect final decision authority and regulatory traceability. These systems face the highest inspection scrutiny.

Can Verification Be Considered Complete Without a Traceability Matrix?

No, not in a defendable, inspection-ready validation model. Traceability is the first thing regulators use to test discipline and lifecycle control. Without a matrix connecting each requirement → to a test → to its result → to the final decision, the entire V&V process is considered incomplete or unprovable.

How Does Software Validation vs Verification Apply in Hybrid Paper–Electronic Workflows?

Verification ensures the digital system configuration correctly enforces the expected roles, data flows, and handover points between paper and electronic control. Validation confirms that the hybrid process actually works without gaps, duplication, or loss of control, including manual interventions. Hybrid models are often more error-prone and, therefore, more heavily scrutinized.

Final Thoughts

Verification and validation are not administrative tasks but formal confirmation that a computerized system is both correctly implemented and suitable for its intended use. Verification demonstrates that the system has been configured according to approved specifications and documented requirements. Validation confirms that it performs reliably under real operational conditions and supports compliant decision-making.

Regulatory authorities are not focused on the volume of test evidence but on whether assurance is clearly justified, traceable, risk-based, and supported by controlled lifecycle execution. A validated system is one that is built correctly, tested with defined intent, approved by Quality, and continuously maintained in a state of control. This is the standard by which software validation and verification are evaluated during inspection.